The next Screen Talks event will be on Monday 8th April, 6.30 pm at Exeter Picturehouse. Dr Jennifer Barnes will introduce Richard III (Laurence Olivier, 1955). Join the event on Facebook and find out more here.

Booking Information: Book online, call the Box Office 0871 902 5730 or buy tickets on the door (half price for students on Mondays).

Dr Jennifer Barnes has written a guest blog post for us, outlining Laurence Olivier’s contribution as director and star and the film’s place in British national culture of the 1950s:

Richard III (1955) is the third and final Shakespearean feature film in which Laurence Olivier (1907-1989) both starred and directed. It follows the patriotic Henry V in 1944 and the internationally renowned Hamlet in 1948. There is much of interest in the film for those interested in Olivier as an actor-director, for those fascinated with Shakespeare on screen, and for those intrigued by the ways in which Shakespeare is adapted to speak to different cultural moments.

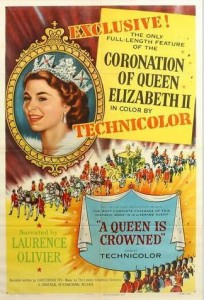

To watch Richard III is to be immersed in the national culture of 1950s Britain following the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II. With its emphasis on colour, spectacle and monarchical imagery, Richard III continually looks back to the Coronation of 1953 and the film offers an extravagant celebration of Britain’s national past and present. Showcasing Richard as the ultimate hero-villain and a “legend of the crown of England,” Olivier’s screen adaptation of Shakespeare’s play revels in a glorification of the national image and of the high cultural values associated with Britain’s national poet. Remembering Britain’s theatrical past through the cinematic present, Richard III draws an explicit parallel between the so-called Golden Age of Elizabeth I and the new Elizabethan age, a parallel that is further cemented by the way in which Richard III continually cites the Technicolor documentary film of Elizabeth’s Coronation, A Queen is Crowned. As the distribution poster announces, the instantly recognisable voice of Laurence Olivier narrates A Queen is Crowned and the mood of national celebration and renewal that it captures is evoked throughout Richard III. Accordingly, the film begins not with Richard’s famous opening soliloquy (“Now is the winter of our discontent…”) but with a fantastic Technicolor Coronation.

My research into the background of the project reveals that Richard III was designed as a prestige production, one that was intended to shore up the reputation of the beleaguered British film industry at home and abroad. Conceived of as a project of both national and international importance, it became the first feature film to be premiered on US television simultaneously with its release in cinemas, reaching an audience of millions. With this in mind it is perhaps no surprise that Olivier’s performance as Richard III is so clearly embedded in cultural memory. The apparently indelible mark left on the role by Olivier has informed incarnations of Shakespeare’s Richard ever since. Anthony Sher, struggling to come to terms with the ghost of Olivier’s Richard whilst preparing to play the part himself, described Olivier’s delivery in the 1955 film as “imprinted on those words like teeth marks.”

Richard III certainly represented an important milestone in Olivier’s career. Six months before the film’s premiere in London, critic John Barber wrote a particularly vituperative article for the Daily Express that accused Olivier of preferring Hollywood to Britain and privileging the screen over the stage. Olivier, said Barber, had “lost his way.” Barber must have particularly enjoyed Richard III. The film presents Laurence Olivier at the helm of a British performance tradition that encompasses other famous actors celebrated for their performances as Shakespeare’s “bottled spider.” Indeed, Richard III includes, amongst others, references to Richard Burbage (1567-1619), Edmund Kean (1787-1833) and Henry Irving (1838-1905). When, in the opening scene, we watch Olivier’s Richard slowly lower a coronet onto his head, we are watching Olivier reassuming what the Financial Times described in 1955 as “that crown of heroic British acting which is his by rights.”

Find out more about Jennifer Barnes’s research here: http://exeter.academia.edu/JenniferBarnes