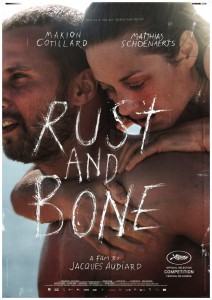

Our next Screen Talks will be on Monday 2nd December, 6.30pm at Exeter Picturehouse. Ryan Sweet, a Phd researcher in the Dept of English at the University of Exeter, will introduce Jacques Audiard’s De rouille et d’os (Rust and Bone; 2012).

Jacques Audiard’s De rouille et d’os (Rust and Bone; 2012) is a film that deals with a number of complex and emotive themes, including the father-son relationship, the struggles of working-class life, the dubious policies of middle management in retail firms, domestic abuse, single parenthood, the animal-human relationship, and, to an extent, the question of whether we should keep powerful and intelligent animals, like orcas, in captivity—many of which we can anticipate based on the trailer alone. Above all, though, as I will suggest in my screen talk, Audiard’s romantic drama is acutely concerned with the practical, emotional, and psychological effects of limb loss and disablement— themselves extremely sensitive topics.

As a researcher working on fictional representations of artificial body parts, I initially suggested giving a screen talk on Paul Verhoeven’s iconic 1987 motion picture, Robocop, a film that’s portrayal of prosthetics is significantly different than that which we see in Rust and Bone. As scholars working on disability in film have noted, Murphy, the hero of Verhoeven’s sci-fi action film, is an archetypal example of a particular type of disabled character that we often see deployed in Hollywood film—the “Techno Marvel”. Like the on-screen portrayals of other characters of this type, the display of Murphy’s hyper-sophisticated prosthetics takes precedence over the effects and implications of his disablement. While Robocop is explicitly evoked in Audiard’s film in a light-hearted exchange between the lead characters—Ali, a boxer, and Stephanie, a former ocra trainer—disablement and artificial-limb use are displayed in a much more realistic light in the latter. Unlike the majority of films that use disability as a significant motif, here we see the day-to-day struggles of limb loss and prosthesis use unreservedly displayed—in a couple of instances we even see how difficult and undignifying going to the toilet can be without the use of real or artificial legs. Though we commonly see disability used in film as a visual sign for a character’s deplorable character, or as a motif that enables a physically or mentally impaired protagonist to appear more heroic for achieving success in the face of adversity, in Rust and Bone we see one woman’s surprising and somewhat unusual response to the psychological, emotional, and physical torment occasioned by double-limb amputation.

A particularly unusual and yet extremely interesting aspect of Rust and Bone is the way in which it eroticises the amputee. As I will suggest in my introduction, this eroticisation can be read to engage with but also to reject a recent cultural interest in the sexual appeal of prosthetics—you may remember from a few years ago the internet rumour that Lady Gaga had opted for amputation “for fashion purposes”! As you will see in this film, prostheses are quickly discarded when sex is on the cards. By drawing the attention of the audience to the film’s use of lighting, shot selection, and close-ups to focalise legs—severed and whole—in the movie, I will raise a number of questions regarding Audiard’s decision to sexualise the amputee. How does the film deal with the loss of sexual self, which often accompanies limb loss? How does one regain libido after experiencing amputation? Are prostheses are turn-on, or should they be hidden from potential sexual partners?

As I will also identify, the film raises some intriguing questions about the role of people with disabilities within the film industry. How can we justify Audiard’s decision to cast an able-bodied actress as double amputee in this film? How, if at all, would this film differ if a disabled actress played Stephanie?

Ryan Sweet is a fully funded PhD student and Graduate Teaching Assistant based in the Department of English at the University of Exeter. His research focuses on the representations of artificial body parts in literature from 1830 to 1914.