Our next Screen Talks event will be on Monday 26th January, 6.00pm at Exeter Picturehouse. Dr Corinna Wagner, Senior Lecturer in C18th Literature, Visual Culture and Medical Humanities, Dept of English and Film Studies at the University of Exeter) will introduce The Elephant Man (David Lynch, 1980).

This event is the first of three ‘Celluloid Gothic’ special events, and ties in with the Art & Soul: Victorians and the Gothic Exhibition at Exeter’s RAMM,

Join the event on Facebook and find out more here.

Booking Information: Book online, call the Box Office 0871 902 5730 or buy tickets on the door (half price for students on Mondays).

Corinna has written a guest-blog post for us on the film:

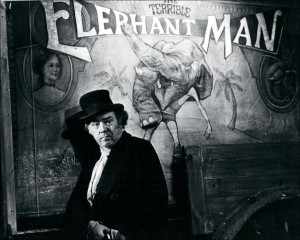

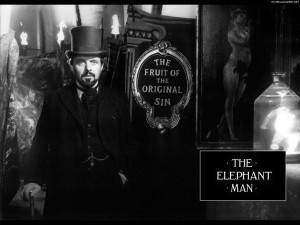

The Elephant Man: Victorian Monstrosities

There is so much to say about this brilliant film: about the methods and choices of the director David Lynch, about the music, about the uses of the Victorian past, and about how Lynch built his narrative on the memoirs of the Victorian surgeon Dr. Frederick Treves, who wrote the medical account of the tragic life of the ‘The Elephant Man,’ Joseph Merrick.

But we can talk about those things (and more) next week at the Screening. For now, I want to focus on some particular issues surrounding medicine, ‘monstrosity’ (to use a 19th century term), and spectacle.

The Normal and the Pathological

‘The showman — speaking as if to a dog — called out harshly: ‘Stand up!’ The thing arose slowly and let the blanket that covered its head and back fall to the ground. There stood revealed the most disgusting specimen of humanity that I have ever seen. In the course of my profession I had come upon lamentable deformities of the face due to injury or disease, as well as mutilations and contortions of the body depending upon like causes; but at no time had I met with such a degraded or perverted version of a human being as this lone figure displayed. He was naked to the waist, his feet were bare, he wore a pair of threadbare trousers that had once belonged to some fat gentleman’s suit.’

This is Treves first encounter with Merrick, as recorded in his 1923 memoirs. Merrick was exhibited in a Victorian freak show. Treves’s language is shocking to us: we expect more objectivity, professional distance, and perhaps care and understanding from our medical practitioners. Yet Treves’s straightforward account underscores our discomfort, our horror at the sight of bodies that don’t fit definitions of normal. Perhaps this seems obvious, but our visceral repulsion to ‘abject’ bodies calls attention to the way we have historically divided the world into categories of normal and abnormal/pathological. Medical science, as Paul Youngquist points out, has built ‘the proper body’ and those who fall outside this category are destined never to experience the privileges that come with being ‘normal.’

Atavism, Degeneration and the Monstrous

Victorian society was anxious about the idea that human society could degenerate, rather than progress. What better genre to express these fears than the gothic? Fears about the tentative nature of civilization and progress produced in gothic literature what Kelly Hurley describes as “new models of the human as abhuman, as bodily ambiguated or otherwise discontinuous in identity” (5). These abhumans or ambiguous, often monstrous characters include Robert Louis Stevenson’s primal Mr. Hyde, Sheridan Le Fanu’s Mr. Jennings and his tormenting monkey-spirit, and H. G. Wells’ human-animal mutants in The Island of Doctor Moreau. We could also include in this list the urban poor who populated Victorian London’s East End, who were often represented as atavistic, animalistic creatures. These figures are all types of animal-human hybrids; they are abject, uncanny beings who we may fear or we may have sympathy for, but who always prompt us to consider the traits that make us human and the qualities that make us civilized. Invariably, they also remind us of how fragile our ordered world is. Among these figures, the Elephant Man looms large: yes, he was Joseph Merrick, a real life individual, but he has also became a character.

Tracing a Tradition

The Elephant Man could be ranked too, among those visually different individuals that defied the ordinary, the normal, the typical. One of the reasons these individuals cause anxiety is because they trouble the categories and distinctions that give us such comfort and security.

According to many observers, historically this became much more the case in the Victorian era. Previously, ‘monsters’ were figures of wonder, but in an enlightened age, they became figures of deviance and dysfunction. The direction of historical change in the ways we see the anomalous body, as Rosemary Garland-Thomson puts it, ‘can be characterized simply as a movement from a narrative of the marvellous to a narrative of the deviant.’ ‘As modernity develops in Western culture,’ she argues, ‘what was once sought after as revelation becomes pursued as entertainment; what aroused awe now inspires horror; what was taken as portent shifts to a site of progress. In brief, wonder becomes error’ (3). Thus, you get the Victorian Freak show.

How do Freaks operate in Culture—then and now?

Rosemary Garland-Thomson also describes ‘freaks’ or the ‘monsters’ as ‘magnets,’ because we attach whatever events or questions we have at any given historical moment to them.

So, where are we now? And where were we in 1980, when David Lynch made this film? What anxieties are betrayed in this version of Merrick’s life? What events stimulated Lynch’s interpretation? In what way has he approached and represented bodily monstrosity? How has he represented the ‘normal’? Is this an overly sentimentalized portrait of Merrick?

And how are we representing ‘monstrosity’ now? In recent years there was a Channel 4 documentary called I am the Elephant Man, about a 31-year-old Chinese man Huang Chuncai. This ‘BodyShock’ special also outperformed BBC2’s Clowns, an examination of the lives of four children’s entertainers, which drew an audience of 1.3 million and a 6% share at the same time. However, I am the Elephant Man wasn’t the biggest performing BodyShock of this year, losing to the portrait of the world’s fattest woman, called Half-Ton Mum, which picked up 4.8 million viewers and an 18% share in January.

Works Cited:

Rosemary Garland-Thomson. Freakery: Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body. New York: NYUP, 1996.

Kelly Hurley. The Gothic Body: Sexuality, Materialism, and Degeneration at the Find de Siecle. Cambridge: CUP, 1997.

Treves, Frederick. The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences. London: Cassel, 1923.

Paul Youngquist. Monstrosities: Bodies and British Romanticism. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2003.

<a href=”https://twitter.com/share” class=”twitter-share-button” data-via=”ExeScreen_Talks” data-hashtags=”screentalks”>Tweet</a>

<script>!function(d,s,id){var js,fjs=d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0],p=/^http:/.test(d.location)?’http’:’https’;if(!d.getElementById(id)){js=d.createElement(s);js.id=id;js.src=p+’://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js’;fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js,fjs);}}(document, ‘script’, ‘twitter-wjs’);</script>