By Jenny Guardado (Georgetown University)

The idea that colonial institutions are fundamental in explaining the divergent development trajectories of New World countries is well-established.[1] In this view, colonial institutions led to longstanding differences in the protection of property rights or the provision of public goods in countries such as the US and Canada on the one hand and a number of Latin American countries on the other, affecting economic growth.[2] Yet, some of the most damaging economic consequences of colonialism also came from individuals’ intent on extraction for self-enrichment purposes, even within the same institutional framework. For instance, in Spanish America, the figure of corregidor or provincial governor, is associated with some of the worst abuses committed against the indigenous population.[3] For this reason, it is important to look into the selection and quality of colonial officials as a key mechanism to understand long-run economic divergence, while holding the type of colonial institutions constant.

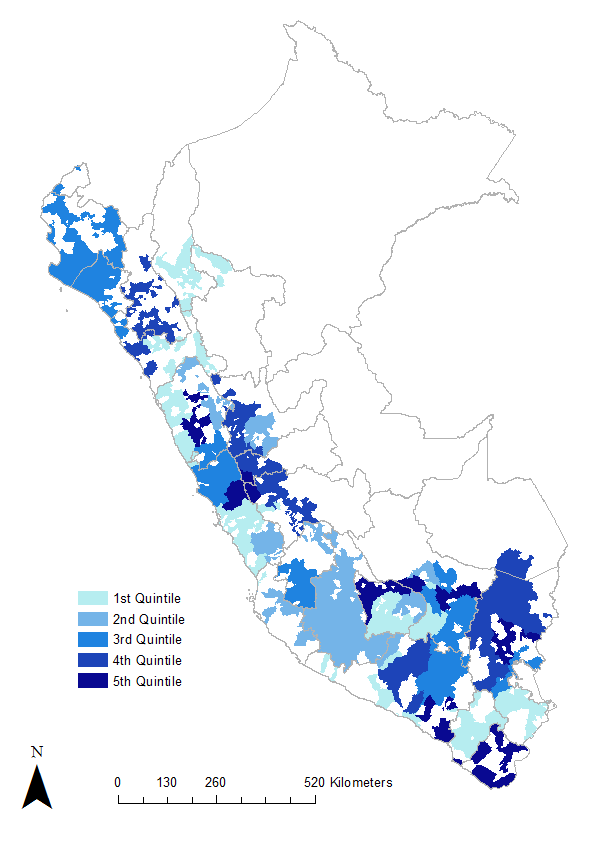

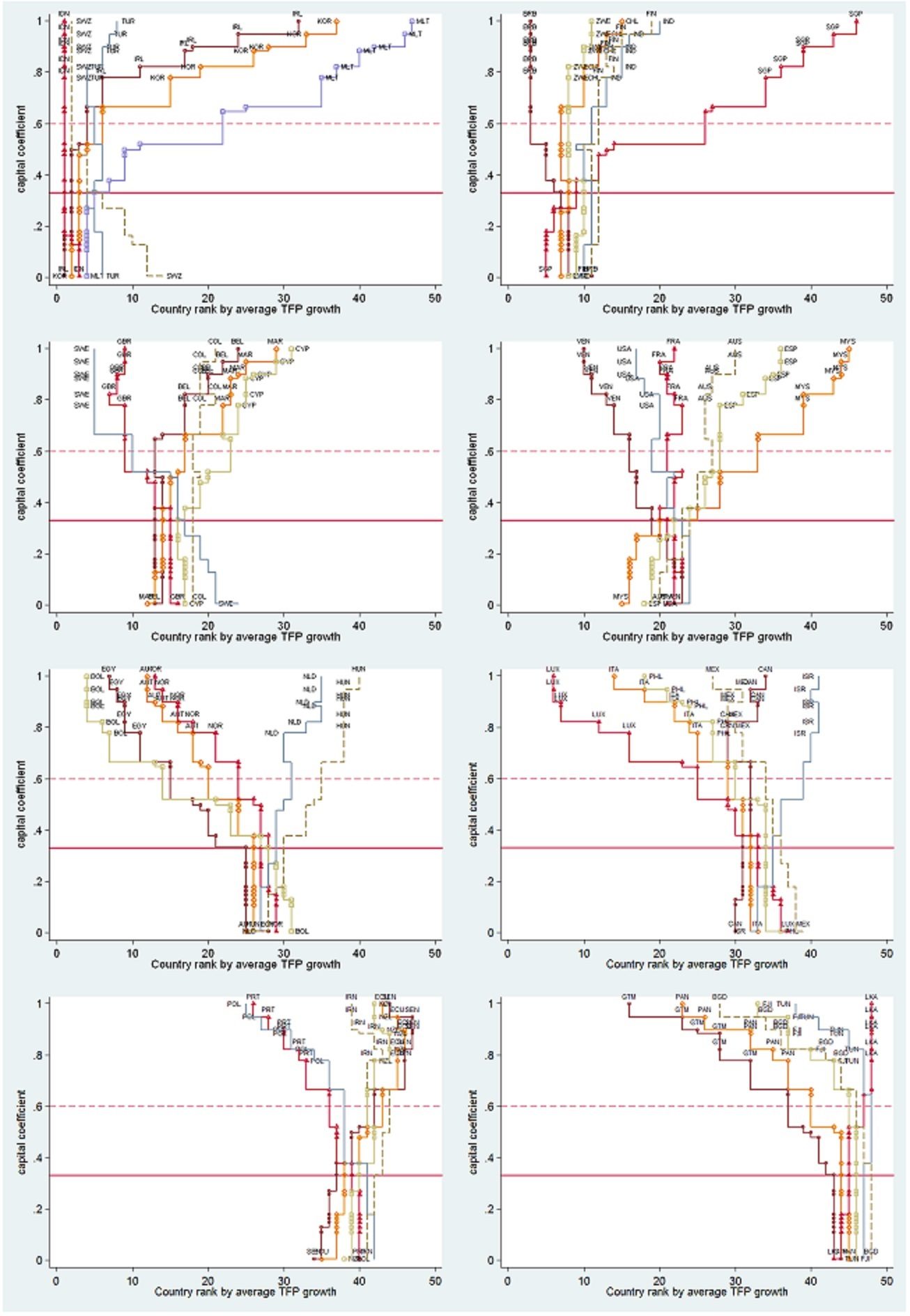

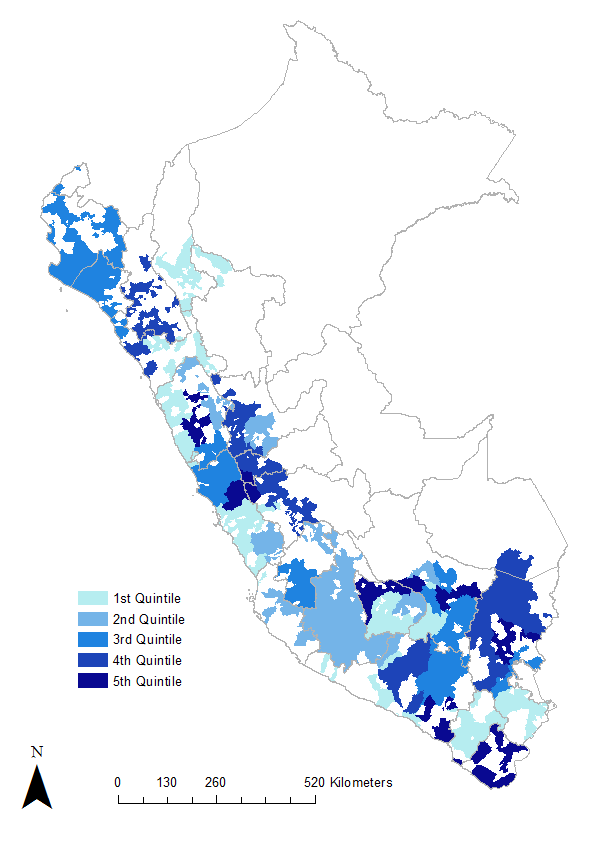

In a recent paper, I do precisely that.[4] Relying on a unique market for colonial offices in the seventeenth and eighteenth century Spanish Empire, I show that at least part of the impact of colonialism can be explained by their role in attracting certain types of individuals to serve in the colonial government. To do so, I collected an original dataset of the prices paid for provincial governorships (corregidores) between 1670 and 1750 to distinguish individuals seeking office for extractive purposes and investigate their long-run impact on economic development within Peru. As a market-based measure of profitability, office prices offer a unique opportunity to distinguish empirically which positions had higher returns to extraction. Furthermore, to avoid concerns of the Crown selectively timing sales when prices are high, I always compare prices at times in which Spain is involved in European Wars – thus less selective and more fiscally pressured – across provinces that only vary in the potential for extraction. Figure 1 below shows the geographical distribution of the provinces’ prices paid between 1670 and 1750, mapped onto current boundaries in Peru.

Figure 1. Current Districts and Office Prices

Results show that office prices were much higher at times in which the Crown relaxed its selection criteria —during fiscal crises caused by European wars—in provinces with greater potential for profit vis-a-vis others. On average, prices were 16% higher in provinces with greater potential to profit from a key extractive activity (known as repartimiento or the forced sales of goods at markup prices) relative to others. This result translates into more than three times the yearly wage of a military captain in the Spanish army at the time. Alternative explanations such as prices reflecting changes in the attractiveness of Peruvian provinces during European wars, or selectivity in sales by the Crown, among others, are not borne out in the data.

Rather, additional analyses using individual buyers’ traits show that provinces with greater opportunities for extraction were more likely to be purchased by “worse” individuals – particularly when the Crown was less selective. In other words, individuals of lower social status, less bound by social and reputation costs, were more likely to pay higher prices to purchase positions with greater returns to extraction. Because social capital and reputation were key mechanisms to enforce compliance with the Crown’s interests in 18th century Spain, these individuals were of plausibly lower quality than those whose career (e.g. military) or social capital (e.g. nobility) were easier to monitor and screen by the Crown. In this sense, office selling allowed a relatively “worse” class of official to rule in the Spanish Empire. Although the practice ended formally in 1750, by then the Crown had sold so many appointments in advance, that buyers were still ruling Peruvian provinces well into the 1770s – on the eve of the nineteenth century independence movements.

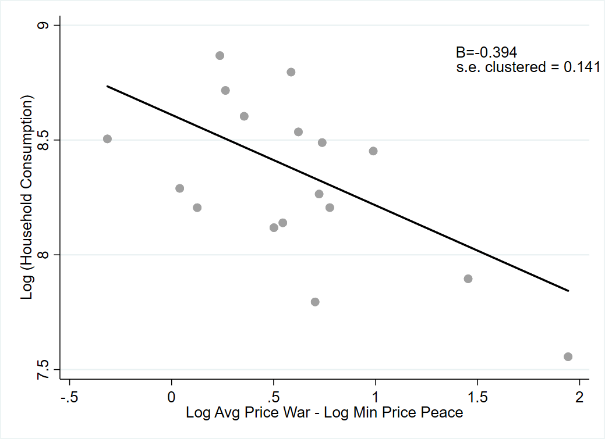

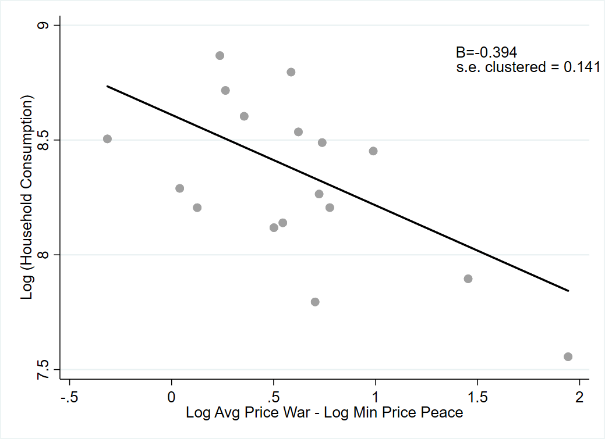

The next question is: did the rule by these individuals influence the long-run economic prospects of these provinces? The answer is yes. Estimates show that a larger gap or difference in office prices at times of low oversight (during wars) relative to periods of high oversight (during peace) is associated with lower household consumption, years of schooling and public good provision. Because province fundamentals – that may influence long-run development – do not vary between war and peace times in Europe, price differences likely capture shifts in the selectivity criteria of the Crown due to fiscal considerations and not other factors. Figure 2 below shows the relationship between the gap in office prices and household consumption. Importantly, this economic gap is already present in 1827 — just after Peru gained independence—suggesting the importance of colonial rather than postcolonial factors.

Figure 2. Office Prices Differences and HH Consumption

Each scatter dot represents the mean of the outcome of interest within each bin plotted against the mean value of the difference in office prices within each bin. The solid line shows the best linear fit using OLS.

One important reason why we observe these effects today is because extraction during this period led to spontaneous rebellions which were usually brutally put down. Detailed data on local rebellions for eighteenth century Peru show that provinces with higher prices paid during European wars relative to peace times experience a higher number of spontaneous uprisings against their colonial rulers in the office-selling period (1673–1751) than immediately afterwards (1752–1780). Furthermore, this relationship is still visible in recent times: districts with higher prices in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries also exhibit greater initial support for anti-government Maoist guerrillas (Shining Path) in the 1980s.

Similarly, political violence also led the indigenous population to limit intentionally its interactions with the Spanish and mestizo world. Data from two centuries show that in provinces with higher provinces the ethnic segregation of the indigenous population started to become visible post office-selling (1780), worsened in the nineteenth century (1876), and is even higher in contemporary times (2013). While limiting interactions may have served to “protect” the community, it might have also reduced the gains from participating in the market.

Put together, these results show the importance of appointment mechanisms and the quality of colonial officers to understand the impact of colonialism on economic development, even for cases sharing the same institutional framework.

References

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2001); “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation. American economic review, 91(5), 1369-1401.

Banerjee, A., & Iyer, L. (2005); “History, Institutions, and Economic Performance: The Legacy of Colonial Land Tenure Systems in India.” American economic review, 95(4), 1190-1213.

Dell, M. (2010); “The Persistent Effects of Peru’s Mining Mita.” Econometrica, 78(6), 1863-1903.

Engerman, S. L., & Sokoloff, K. L. (1997); “Factor Endowments, Institutions, and Differential Paths of Growth Among New World Economies.” How Latin America Fell Behind, 260-304.

Guardado, J. (2018); “Office-Selling, Corruption, and Long-Term Development in Peru.” American Political Science Review, 112(4): 971–995.

Juan, J. (1826). Noticias Secretas de América, Sobre el Estado Naval, Militar, y Politico de Los Reynos del Perú y Provincias de Quito, Costas de Nueva Granada y Chile. (Vol. 2). Taylor.

Moreno Cebrián, A. (1977); El Corregidor de Indios y La Economía Peruana del Siglo XVIII: Los Pepartos Forzosos de Mercancias. Editorial CSIC-CSIC Press.

Endnotes

[1] Engerman and Sokoloff (1997) and Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (2001).

[2] Banerjee and Iyer (2005) and Dell (2010).

[3] Juan (1826) and Moreno Cebrián (1977).

[4] Guardado (2018).