By Mostafa Beshkar (Indiana University at Bloomington) and Ali Shourideh (Carnegie Mellon University)

A salient feature of international trade is the presence of trade imbalances. How should governments conduct their trade policy under trade imbalances? In a forthcoming paper we ask if trade imbalances influence governments’ choices of trade policies under a standard dynamic trade model.[1] This analysis could shed light on the policy debates in recent years where a widening trade deficit has prompted calls for protectionist policies in the United States and other countries with major levels of trade deficit.

Method

We use a dynamic economic model to study the potential impact of fluctuations in trade volumes and trade deficits on the unilaterally-optimal choice of trade and capital control policies—namely, policies that maximize a measure of welfare of the home country disregarding their effects on the rest of the world.

By using a dynamic framework in which international lending and borrowing—and hence trade imbalances—may occur endogenously, our analysis departs from most of the trade policy literature that focuses on static models with the assumption of balanced trade or an exogenously-given trade deficit.

Using a dynamic—as opposed to static—framework has several advantages for policy analysis. First, it allows researchers to study the relationship between economic fluctuations and trade policy. The vast literature on trade policy—which has concerned itself mostly with static impacts of trade policy—cannot properly address this relationship.

A second advantage of a dynamic framework for trade policy analysis is the ability that it affords researchers to study the potential interdependence between trade and capital control policies. This potential policy interdependence may have important implications for the design and benefits of trade agreements. For example, while trade agreements such as the WTO restrict trade policies, they leave exchange and capital controls to the discretion of the member governments. Therefore, following negotiated trade liberalizations, governments may have an incentive to use exchange and capital controls more actively to affect trade flows to their advantage. It is notable that shortly after its accession to the World Trade Organization, China was frequently accused of manipulating its exchange rate to affect the flow of goods and services.

The use of a dynamic framework is also advantageous for quantitative analysis of trade policy as it could match observed trade flows that involve substantial trade imbalances. The balanced-trade assumption in the previous literature poses a problem for quantitative analysis as it violates the observed trade data. The static trade literature has so far dealt with this problem in one of two ways. The first approach is to introduce aggregate trade imbalances as constant nominal transfers into the budget constraints. The second approach is to “purge” the data from imbalances, namely, conducting the analysis under the counterfactual in which trade is balanced.[2] A dynamic approach, however, provides a more satisfactory solution by allowing trade imbalances to occur endogenously

Results

A key determinant of optimal trade and capital control policy in a given period is the productivity of the home country relative to the rest of the world in that period. The time variation in these policies, however, depend critically on the set of policy instruments that are employed by the government.

An important case is one in which trade taxes are the only policy instruments at the government’s disposal—i.e., there are no capital control taxes. Under this scenario, there is significant variation in optimal trade policy over time. In particular, in the absence of capital control taxes, the optimal level of import restriction and export promotion—namely, import taxes and export subsidies—is counter-cyclical.

The counter-cyclicality of import tariffs and export subsidies reflects the government’s desire to improve the country’s intertemporal terms of trade. That is, individual households ignore their collective effect on the world interest rate and, thus, save and lend too much in booms and borrow too much in downturns, which negatively affects the interest rate for domestic households. To correct for this “inefficiency,” the government’s optimal policy response would be to decrease the price of consumption in high-productivity periods relative to low-productivity periods. This objective may be achieved by applying lower import tariffs together with higher export subsidies in low-productivity periods.

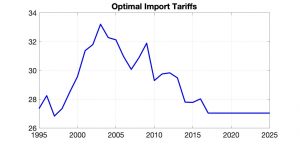

Figure 1 Panel A

Figure 1 Panel A

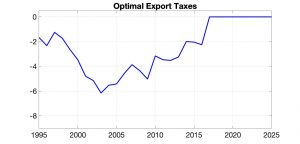

Figure 1 Panel B

Figure 1 Panel B

Figure 1 depicts the optimal level of import and export taxes that we calculate in our paper, for the United States for each year from 1995 to 2016. As can be seen in this figure, over this time period optimal tariffs vary between 27% and 33%, and export subsidies vary between zero and 6%. Nevertheless, if capital controls are used in lieu of export subsidies, the time-variation of import tariffs is virtually eliminated—with tariffs hovering around 25% for the entire period.

The gradual increase in trade protection in the first-half of the time period in Figure 1 reflects an optimizing government’s motivation to discourage borrowing by households from the rest of the world during this relatively fast growth period. Conversely, the gradual decline in the optimal level of protection after 2003 reflects the government’s desire to encourage domestic consumption in lieu of lending to the rest of the world.

Despite the significant time-variation in import taxes and export subsidies that is depicted in Figure 1, the total level of trade protection, measured by the product of import and export taxes, namely, (1+import tax)*(1+export tax), remains relatively constant (around 25%) for the entire time period. In other words, the desired relative price of domestic and imported goods may be implemented using a 25% import tariff alone. Nevertheless, to induce the desired interest rate—or, equivalently, the desired relative price of aggregate consumption across periods—both tax instruments are necessary. This observation suggests that the famous Lerner Symmetry Theorem should be interpreted cautiously in practice.

Remaining Questions

Given the insights we have discussed above, an interesting question that could be addressed in future research is whether capital controls could serve a useful purpose as a flexibility mechanism in trade agreements. Flexibility may be a desirable feature for trade agreements for at least two reasons. First, if political economy preferences are subject to shocks in the future governments will negotiate an agreement that includes a mechanism for policy flexibility such as the WTO Agreement on Safeguards.[3] Second, if trade agreements must be self-enforcing, flexibility in capital control policies could reduce the governments’ incentive to renege on the agreement at times when a surge in imports or a widening trade deficit increases temptations to leave an international agreement.[4]

The possibility of time variation in trade policy is also important in understanding the potential relationship between the state of the economy and optimal trade policy. This is particularly so in order to understand the pattern of optimal trade taxes over the business cycle and the potential relationship between the growth rate of the economy and the optimal conduct of trade policy. Our model offers a tractable framework in which to explore these issues.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is worth noting that although the magnitude of changes in optimal tariffs are significant, the quantitative analysis suggests that the gains from this variation are small. In particular, a constant tariff can achieve almost all of the gains from implementing the optimal policy. This finding also implies that under our framework, the negative externality of optimal capital control taxes on the rest of the world is very small.

These quantitative results, however, should be taken with a grain of salt as they hinge on various simplifying assumptions, including the assumption that labor is the only factor of production and no investment in physical capital takes place. Enriching the model by allowing for the possibility of physical capital formation could potentially magnify the welfare effects of capital control policies.

References

Bagwell, K., and R. Staiger, (1990); “A Theory of Managed Trade.” American Economic Review, 80(4): 779-795.

Maggi, G., and R. Staiger (2011); “The Role of Dispute Settlement Procedures in International Trade Agreements.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126, (1): 475-515.

Beshkar, M., and E. Bond, (2017); “Cap and Escape in Trade Agreements.” American Economic Journal – Microeconomics. 9(4): 171–202.

Beshkar, M., and A. Shourideh, (2020); “Optimal Trade Policy with Trade Imbalances.” Journal of Monetary Economics.

Ossa, R. (2016); “Quantitative Models of Commercial Policy.” Published in K. Bagwell and R. Staiger (eds) Handbook of Commercial Policy. Amsterdam, Elsevier.

Endnotes

[1] Beshkar and Shourideh (2020).

[2] See Ossa (2016).

[3] See Maggi and Staiger (2011), Beshkar (2010), and Beshkar and Bond (2017) among others.

[4] The logic here is similar to that of Bagwell and Staiger (1990).