We would like to thank The School of Economics, University of Nottingham, for hosting and sponsoring the 6th InsTED Workshop. We would also like to thank the Nottingham School of Economics for incorporating The World Economy Lecture into the InsTED Workshop, and Wiley for sponsoring this. The workshop took place from September 20th-22nd, 2019. Special thanks go to Roberto Bonfatti, Giovanni Facchini, and Alejandro Riaño as joint chairs of the local organizing committee, and Hilary Hughes for taking care of the local organizational details.

The program comprised of 24 papers ranging over four broad topics at the intersection of institutions, trade and economic development. The first was factor allocation, productivity, and economic development, focusing on how income shocks are transmitted through distortions in the economy, and how the distortions might be removed to promote development. The second topic examined trade policies, externalities, and agreements, by developing frameworks that go beyond the conventional two-good or partial equilibrium structures, and introducing the possibility that trade agreements may actually generate negative externalities rather than just removing them. The third concerned international trade and economic development, again focusing on distortions but this time through trade policies and also labor market institutions such as minimum wages. The fourth was on political institutions and economic development, focusing on different aspects of the role of democracy on capital formation and growth.

There now follows a summary of all the papers presented at the workshop, organized under the four topic headings above. A bibliography, together with links to papers where available, is provided at the end. Please note that for brevity the summary mentions presenters’ names but not those of their co-authors. This information is contained in the bibliography.

Factor Allocation, Productivity, and Economic Development

An influential view in economics holds that the efficient allocation of resources to production is central to the process of increasing productivity and hence economic development. Following this view, the market-and-institutions approach aims to set institutions and government policies so that development emerges spontaneously through the efforts of individuals.

Income Shocks, Distortions and Development

The first keynote address by Robin Burgess considered the “stubborn poverty” problem: the issue that even as countries build momentum behind growth and development, many people are left behind in poverty. The purpose of the paper he presented was to understand why some people stay poor even as growth and development take off, with the ultimate objective of designing policies to facilitate the movement of the poorest out of poverty as part of the process of economic development. Many government policies already exist for this purpose that make available credit, training, and grants to promote entrepreneurship. In motivating his talk, Burgess argued that we need to understand why people stay poor even when such policies are available in order to evaluate the extent to which policy programs to mitigate poverty can be effective.

In essence, the paper tests between two views of why people stay poor. According to the first view, there is equal access to opportunity, but people have different innate mental and physical traits that ultimately determine their standard of living. According to this view, peoples’ allocation of their talents to the production process is efficient, and the only way to lift them out of poverty is through social protection programs facilitated through the development process. A crucial implication of the fact that the talents of the poor are already efficiently allocated is that making more assets available to them will not help lift them out of poverty in the long run. According to the second view, it is not variation in peoples’ talents that determines their standards of living but variation in their access to economic opportunities. The talents of those who lack access to opportunities are consequently misallocated. A crucial implication of this second view that contrasts with the first is that a capital transfer will help to facilitate the efficient allocation of the talents of the poor, thus helping to lift them out of poverty, and facilitating development in the process.

The test is implemented using a randomized controlled trial that implements a positive shock to capital over 23,000 households across the wealth distribution in Bangladesh over seven years. Of these, 4,000 households were randomly allocated an endowment of one year’s worth of personal consumption expenditures. The allocation was the same across households, but households started with different asset baselines due to pre-existing variation. The surprising result of the study is that households whose asset base is pushed over a threshold are then able to accumulate capital for themselves, while those below the threshold are not. This suggests the existence of a poverty threshold or ‘trap’, whereby only transfers large enough to push beneficiaries over the threshold will reduce poverty in the long run. The implications are profound and far-reaching. Previous tests may have falsely attributed support to the first view of why people stay poor by failing to make transfers that were sufficiently large to push people over the threshold. And policies and institutional changes to facilitate the availability of credit, say, must make capital available to the poor on a sufficiently large scale to push them past the poverty threshold if they are to move into the range where they can allocate their talents efficiently.

Technological innovations that foster trade integration, especially in shipping technology, create positive income shocks that may reduce conflict, in turn promoting economic growth and development. The paper presented by Reshad Ahsan tests the first part of this proposition against an impressive 250 year sweep of data spanning 1640-1896. The paper tests the idea that the decline in intra-European conflict from the late Middle Ages to World War One can be explained partly by the increase in Atlantic trade. It finds that if any two European countries jointly increase their trade integration with the New World by one standard deviation, then the probability that they will be at war with each other decreases by 12.33 percentage points; an economically significant reduction from a baseline probability of war of 14.3 percent. The endogeneity of New World integration is addressed using exogenous, weather-based shocks to trade between Europe and the New World.

Climate change represents another kind of shock that, through yield volatility, is having a negative effect on the incomes of poorly insured farmers in developing countries. João Paulo Pessoa presented a paper that examined two different channels through which yield volatility can have an effect on the incomes of poor farmers in India. The paper develops a general equilibrium framework with portfolio choice to allow farmers to respond to a decline in yields by substituting towards other crops. The model also captures risk aversion among farmers. So it can explain how farmers may not substitute away from crops whose average yields decline because they fear greater yield volatility from the crops that they might otherwise have substituted towards. The model can also capture declines in welfare from the direct effect of increases in the volatility of crop yields. Despite allowing for these subtleties, they find that the most important negative welfare effects of climate change on poor Indian farmers come through sharp falls in mean crop yields through temperature rises.

Conflict, Misallocation, and Development Failure

If positive income shocks can facilitate development then negative income shocks can certainly precipitate development failure through the onset of intranational conflict and ultimately civil war. The paper presented by Beatriz Manotas-Hidalgo re-examined the extent to which income shocks cause conflict across Africa, by studying how different types of commodity price shock induced by weather shocks affect the possibility not just of armed conflict but of ‘civilian conflict’ such as riots as well. Her results confirmed the view that when a society is more ethnically fractionalized, a negative income shock increases the probability of conflict. But surprisingly, she also showed that while positive agricultural and mineral price shocks increase the probability of civilian conflict, they decrease the probability of armed conflict. This heterogeneity emphasizes the importance of moving beyond a simple ‘opportunity cost of conflict’ view in seeking to understand how conflict arises.

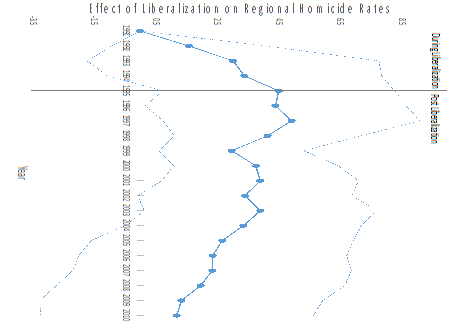

Hâle Utar presented a paper examining the effects of violence on allocation by focusing on the Mexican drug war. The drug war brought about a surge in violence as a result of which the homicide rate tripled from 800 to 2400 between 2000 and 2010. Utar assumes that drug-related violence disrupts the ability of productive factors to allocate to the production process, allowing her to use the homicide rate as an instrument for violence that causes negative income shocks through allocation failure. Her results show that doubling the homicide rate brings about a 4 percent reduction in plant-level employment, a 6 percent reduction in output, a 2 percent increase in the price level and a 4 percent reduction in productivity. These magnitudes are significant enough to bring about plant closures and cause long-term damage to the Mexican economy.

Infrastructure, Uncertainty, and Economic Development

It is tempting to think that improvements in infrastructure should always help with the process of economic development by facilitating the efficient allocation of resources across a national economy. But Niclas Moneke showed that was not the case for Ethiopia when the provision of infrastructure was in the form of a road network that led to the entry of foreign firms that were more productive than domestic ones. Offsetting this effect, however, was the introduction of an electricity network that allowed domestic manufacturing firms to adopt modern technology, thereby enabling them to adopt modern technology and increase productivity.

Moneke was able to obtain remarkably detailed individual-level occupational choice data for Ethiopia in three waves spanning 1999 to 2016. To address endogeneity concerns over the location of the electricity network, he exploited plausibly exogenous variation in a location’s electrification status relative to newly opened hydropower dams. To address endogeneity concerns over the location of the road network, he constructed a least-cost network arising from an implementation of Kruskal’s and Boruvka’s minimum-spanning tree algorithms to solve for a single, purely distance-driven road network that connects all district capitals with at least one road. From this approach, he was able to present causal evidence that improved transport infrastructure causes decreases in manufacturing employment. But he also showed that this adverse effect of improved market access on manufacturing is reversed via improved productivity with additional access to electricity.

Trade Policies, Externalities, and Agreements

It is now broadly accepted amongst economists that international trade policies can create negative externalities, in which case a key purpose of a trade agreement is to find a way to neutralize those externalities while liberalizing trade in the process. These insights have been established within the context of classic two-good or partial equilibrium models, wherein trade is assumed to be balanced.

New Trade Policy Models that Go Beyond the Classic Two-Good or Partial Equilibrium Structures

The second keynote address by Giovanni Maggi considered the widespread controversy surrounding so-called ‘deep trade agreements’ such as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership and the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement. (Note that the two keynote addresses were sequenced to suit the schedules of our speakers.) Maggi explained that, according to the dominant paradigm in the economics of trade agreements, unilateral trade policy creates a terms-of-trade externality, and the purpose of a trade agreement is to internalize this externality, thus raising world welfare. Despite opposition from some quarters, this view underpins the broad sense that ‘shallow trade agreements’ concerning tariffs have broadly been beneficial to the countries that have signed them over the post-World War II period. However, recently there has been far more controversy around the deep agreements that also impose restrictions on so-called behind-the-border measures such as regulations covering the environment, investment, and labor standards. Maggi highlighted that this controversy centers on the fact that lobbying by firms appears to be generating externalities of its own through these agreements, rather than agreements neutralizing pre-existing externalities.

Maggi presented a model in which either shallow or deep agreements are possible. There is a continuum of small countries, which isolates the role of lobbying by ruling out terms-of-trade manipulation by individual countries. There is also a large number of goods, and each country can produce multiple goods, each from a specific factor with which it is endowed. Crucially, production and export subsidies are not allowed in his framework, which creates a role for lobbying. As a baseline, he first considered a model with no domestic distortions. The outcome in this set-up is a shallow trade agreement involving tariffs only, that increases welfare by pitting exporter interests against import-competing interests. In the non-cooperative outcome, only import-competing interests are represented and this undermines efficiency. In a shallow agreement, exporter interests are also represented, being pitted against import-competing interests, giving rise to countervailing lobbying. In effect, in an agreement governments collude to achieve a more efficient distribution that accommodates the interests of exporters, which improves national and global welfare.

His talk then moved on to consider deep agreements and the circumstances under which they may actually undermine welfare. He did this by first introducing local consumption externalities to the framework, such as local pollution generated by cars. This provides a rationale for domestic policy intervention and thus creates a role for deep agreements. In non-cooperative equilibrium, consumption taxes are set at their efficient Pigouvian levels, so anything that causes a change from these levels is bad for welfare. The cooperative equilibrium of an agreement reduces efficiency since governments collude to favor producers at the expense of consumers. Second, he replaced the consumption externalities with production externalities, such as local pollution generated by firms. In this case, the trade agreement pits domestic producers against foreign producers since they have opposing interests regarding domestic taxes. Assuming that the power of producers is reasonably symmetric, and agreement restores the countervailing feature of lobbying, this time across interest groups in different countries, an agreement can increase welfare. As Maggi acknowledged, this framework ‘stacks the deck’ against finding positive welfare effects of trade negotiations by ruling out market power and cross-border externalities. Towards the end of his talk, he introduced terms-of-trade effects and showed that a deep trade agreement will only reduce global welfare if the aggregate political power of producers is sufficiently large to negate the benefit from the agreement of neutralizing the terms-of-trade externalities.

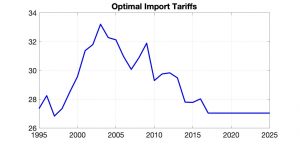

Industrial policy has risen up the policy agenda in many countries recently. The paper presented by Ahmad Lashkaripour develops a model that makes it possible to consider optimal trade and industrial policy simultaneously in a general equilibrium setting, while the prior literature on industrial policy tends to focus focuses only on a partial equilibrium setting. Lashkaripour’s model has multiple industries featuring increasing returns to scale, and two types of policy instrument: industry-level export and import taxes, referred to as instruments of trade policy; industry-level production and consumption taxes, referred to as instruments of domestic policy.

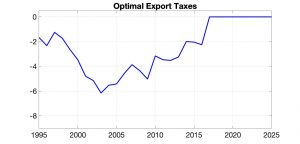

The first setting that Lashkaripour explored was one of restricted entry, whereby the number of firms in a given industry is given. Only the home government is allowed to set policy while the rest of the world remains passive. In this case, import taxes are shown to be redundant: optimal export taxes are regulated by the industry-level trade elasticity and equal to the optimal mark-up of a multi-product monopolist. Meanwhile, optimal production taxes are corrective Pigouvian subsidies that eliminate firm-level mark-up heterogeneity in the local economy. Surprisingly, when domestic policies are available, optimal trade taxes are identical to those in a competitive model; they do not target the profit-shifting margin. The next setting was one of free entry. Here, taxes are able to induce firm delocation across international borders and industries. As a result, import taxes are no longer redundant and optimal production taxes no longer serve only a basic Pigouvian function. Instead, the optimal policy reflects the fact that each instrument plays a distinctive role in improving the terms of trade. An interesting question that can be addressed within this framework is how the unilaterally optimal policy compares to an optimal cooperative policy that eliminates inefficiencies at the global level. Lashkaripour used his framework to argue that if industry-level trade elasticities are sufficiently large, while scale elasticities exhibit sufficient heterogeneity across industries, then the gains from the cooperative optimal policy will dominate those of the unilateral optimal policy. This provides conditions under which a country will find it worthwhile to join a deep trade agreement that restricts the use of both types of policy.

Mostafa Beshkar took the discussion of trade agreements in a different direction by relaxing the standard assumption that trade is balanced. Relaxing this assumption necessitates modelling intertemporal dynamics because allowing for trade imbalances implies exchanging consumption today for consumption in the future. The framework that Beshkar develops to incorporate these features makes it possible to ask how governments should conduct their trade policy under trade imbalances. The biggest issue for trade policy raised by the possibility of trade imbalances is the fact that governments can substitute capital controls for trade policy. Consequently, following the negotiation of a trade agreement, there may be scope for governments to use capital controls to manipulate the terms of trade, thus potentially undermining the trade agreement. The model that Beshkar presented provides a framework to think through this type of issue.

The framework that Beshkar develops combines two models from the prior literature, one capturing optimal trade policy and the other capturing optimal capital controls to provide a new model that features both types of policy. This framework can be used to address such issues as the cyclicality of trade policy over time, the interdependence of trade policy and capital controls, and the potential effects of trade imbalances on trade policy. The framework features a two-country Ricardian model with time-varying labor productivity. The variation in productivity over time creates a role for international borrowing and lending. The fact that productivity varies over time creates a role for two instruments to be used simultaneously. In the absence of capital controls, both import and export taxes are necessary to implement optimal policy: one to manipulate the international terms of trade and the other to manipulate the intertemporal terms of trade. This contrasts markedly with the static two-good model in which one of these trade taxes would be redundant. The paper goes on to show that if the use of trade taxes is constrained by an international trade agreement then the government could use capital controls to restore a fraction of its constrained policy space.

While not modelling trade policy directly, the paper presented by Lena Sheveleva provides a new ‘minimal model’ of multi-product firms that can be used to test the implications of trade liberalization on productivity improvements as high productivity firms displace those with low productivity. In the model, any differences between large and small scope exporters that emerge in the model are due to aggregation across different numbers of products. The proposed model makes it possible to test whether differences between large and small scope exporters are greater than would be expected to arise if firms were just a collection of otherwise unrelated products driven by random variety shocks. She uses her framework to test whether tougher competition does, in fact, drive multi-product firms to concentrate their sales in the top ranked products even if their scope does not change. The results she presented showed that once the level concentration implied by randomness is controlled for, the effect of market size on concentration becomes more pronounced both in terms of magnitude and statistical significance, suggesting that reallocation of resources across products in response to trade liberalization shocks may play an even more significant role than previously thought.

WTO Institutional Design

How should the rules of the World Trade Organization (WTO), and its predecessor the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), be designed to maximize the efficiency of outcomes for members, especially in the face of trade shocks that could lead to disputes? David DeRemer’s paper follows the literature in asking when governments will choose remedies for violation of a trade agreement to ensure compliance with the rules, and when they will choose remedies that allow a breach of the rules but ensure that appropriate compensation is provided to those adversely affected. The law and economics literature has argued that the former approach defines a ‘property rule’ while the latter defines a ‘liability rule’. For concreteness, DeRemer couched his discussion in terms of the noteworthy evolution of the majority of non-tariff measures (NTM) from a system of liability rules under the GATT to property rules under the WTO, while actionable subsidies and non-violation complaints have remained as liability rules.

DeRemer’s model features two governments negotiating over several NTMs simultaneously, where each measure operates in a separate market that does not affect the others. There is a non-cooperative optimal policy that maximizes its government’s payoff function, and a cooperative policy that maximizes the sum of both governments’ payoff functions. The optimal policies depend linearly on unverifiable shocks to home and foreign preferences. The paper focuses on the range of the parameter space where there is a conflict of interest between governments over NTMs. If the difference in the payoffs between cooperative and non-cooperative policies is small, the policy is called a ‘low conflict policy’, and if large it is called a ‘high conflict policy’. The analysis then focuses on whether the governments should choose a property rule or a liability rule to remedy a violation of an agreement over a particular type of NTM. Achieving compliance is more difficult on actionable subsidies and non-violations because they are ‘high conflict policies’, and so a larger number of disputes is expected. Therefore, DeRemer’s framework suggests these policies will be subject to liability rules to minimize the damage done by disputes, explaining what we see in practice. As for the progression from liability rules in the GATT to property rules in the WTO, the framework suggests this results from increases in gains from coordination over time, relative to the expected costs of disputes, and such coordination gains have indeed occurred due to falling trade costs.

Adam Jakubik considered how WTO rules and flexibilities create a predictable trading environment. His paper argues that WTO commitments create a predictable trading environment by shaping members’ trade policy responses to import shocks, incentivizing a move away from unilateral tariff increases towards contingent protection, and anti-dumping in particular. His econometric implementation uses a recently available database of bound tariffs that accounts for countries’ implementation periods and changes of tariff-rate commitments over time, rather than just time-invariant final bindings hitherto used in the empirical literature. The results he presented showed that as import shocks become larger, countries increase tariffs within the tariff binding, or use contingent measures depending on the level of tariff water. An important implication of their analysis is that the WTO Agreement reduces trade policy uncertainty, not just by setting a maximum allowed tariff, but also by reducing the probability of using tariff water to retaliate. This is accomplished by providing other flexibilities that are designed to be more predictable, such as tariff bindings that must be removed within a set period of time.

Along similar lines, Michele Imbruno examined how Chinese tariff bindings adopted as part of its entry to the WTO affected Chinese firm-level imports. The results he presented suggest that a decline in trade policy uncertainty allows Chinese firms to access a greater variety of imported foreign goods, because the payoffs to entering the foreign market are more certain. The newly available imported goods are also associated with higher quality. At the same time, tariff bindings prompt more Chinese producers and trade intermediaries to start importing for the first time, thus allowing a greater number of firms and consumers to enjoy potential gains from imports.

International Trade and Economic Development

In classical economics, the removal of distortions created by trade policy represents one of the most significant ways to promote efficient resource allocation and hence economic development. Recent advances in techniques to causally identify the effects of exogenous trade liberalization shocks, together with the greater availability of data, has made it possible to test for the logic of classical economics in the data.

Trade Distortions and Economic Development

The paper presented by Beyza Ural Marchand looked at the effect of exogenous trade liberalization in Vietnam on intergenerational mobility. The United States (US)-Vietnam Bilateral Trade Agreement, signed in December 2001, led to an immediate drop in US tariffs against Vietnamese exports of 21 percentage points. The logic underpinning the paper is that while trade liberalization can improve economic efficiency as workers relocate to the expanding export sector, if low intergenerational mobility reflects rigidities in the labor market and workers cannot move, trade liberalization may end up causing an unexpected increase in inequality. It is, of course, possible that international trade worsens intergenerational mobility by lowering the returns to skills and thus the incentive to invest in education.

The results Marchand presented showed that the reduction in US tariffs applied to Vietnamese exports actually increased intergenerational skill mobility. Interestingly, this effect is visible only for individuals employed in the manufacturing industry and not agriculture and mining. This is consistent with the observation that most of the export expansion was in manufacturing. In order to further investigate the effect of trade liberalization on human capital investment, she differentiated between the individuals who are the oldest son within households and individuals who have birth order of two or larger. Controlling for education, location, and other labor market characteristics, one should not observe different effects if resources are allocated efficiently within households. The results Marchand presented show that the effect of the export shock on intergenerational mobility is in fact limited to firstborn sons.

Facundo Albornoz’s paper considered a shock going in the opposite direction. In mid-1997, the US suspended preferential tariff rates on over 100 different imports from Argentina, granted under the generalized system of preferences (GSP) program, affecting over a third of Argentinian exports to the US. Particularly because this represented retaliation arising from a separate dispute over the protection of intellectual property rights, the tariff increases can plausibly be taken as exogenous. Comparing the reactions of the firms affected by the suspension with the behavior of firms whose products were unaffected by tariff changes, Albornoz showed that the tariff increase induced some firms to stop exporting to the US market altogether. Surprisingly, for those firms that continued to export, there was no significant reduction in the volume of their exports because those firms were able to rebalance towards exporting goods that were not affected by the suspension. So more resilient exporters are able to partially circumvent the tariff increases through a (potentially inefficient) shift of resources across products. Even more surprising was the finding that essentially all the results obtained for the US market carry through to third markets, where there was no policy change regarding imports from Argentina.

A complementary perspective was provided by Florian Unger in the paper he presented. He considered the effect of corporate tax reforms on the exports of multi-product firms. For the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, the average statutory corporate tax rate has fallen from 39.9% in 1990 to 27.5% in 2014. In contrast to the previous paper, these tax reforms tended to affect all exports of a particular firm equally. The theoretical model introduces tax policy to multi-product firms. The model shows that the reduction of the corporate tax rate in a particular destination leads to more intense competition in that location as exporters reduce product scope in that destination, focusing on their better performing products. The paper tests the predictions of the model using data from the World Bank Exporter Dynamics Database combined with information on corporate tax rates over the period 2005-2012. The resulting dataset covers firm dynamics in 70 origin countries in all their export destinations, and corporate tax reforms in 49 destination countries. The results that Unger presented show strong support for our theoretical predictions that a reduction in the destination tax rate reduces the number of exported products, while increasing the exit of exporters to that country. Moreover, using detailed information on firm export sales by product and destination, he was able to show that a lower corporate tax rate in the destination country increases the within-firm skewness of export sales to that destination, which reinforces the theoretical mechanism.

Yet another perspective was provided by Alejandro Riaño, with his examination of export subsidies in Nepal. Nepal is the third poorest country in Asia. Moreover, its exports are highly concentrated among only five HS6-digit products, with 85% of exports going to only five countries, with 80% of these going to India alone. In 2012, the Nepalese government introduced the Cash Incentive Scheme for Exports (CISE) in order to try to overcome frictions in exporting and thereby increase export diversification. Accordingly, CISE is an ad valorem cash subsidy to exports of a select group of products available only for exports sold in countries other than India. The econometrics are based on customs transaction data for the period 2011-2014 combined with information on subsidy payments to individual firms. The CISE subsidy is available to 24 industrial and 7 agricultural products such as carpets, pashminas, tea, coffee and spices. These products accounted for 41% of total export value in 2011. The results that Riaño reported show that, relative to the control group, firms that received the subsidy increase the number of destinations (other than India) they sell to by 10-12% and the number of products included in the CISE scheme they export by 6-7%. And just as the theory in his paper predicts, the subsidy did not affect the intensive margin of targeted product-destinations, i.e. average exports per product, destination and product-destination combinations. But the results suggest that the scheme may not be economically efficient given its high fiscal cost.

While the removal of distortions to trade promotes efficient resource allocation, one of the main channels for rent-seeking in developing countries is through distortions to trade policy. The paper presented by Adeel Malik is among the first to provide a systematic empirical assessment of the impact of political connections on protectionism. Focusing on Egypt, it develops a unique dataset to identify, at the international standard industrial classification (ISIC) 4-digit level, which products were being produced by crony firms that had links to the Mubarak regime. The paper then argues that the events of ‘September 11th’ exogenously triggered the European Union (EU) to successfully push for a trade deal with countries in North Africa, resulting in the installation of a large number of NTMs on imports. The key finding of the paper is that crony firms have a much smoother experience with the implementation of NTMs than firms that are not politically connected. For example, where NTMs involve inspections, inputs imported by crony firms are ‘waved through’ at the border, while those imported by other firms are subjected to long delays. Thus, the paper breaks new ground by demonstrating the endogeneity of trade distortions to crony influence.

One of the most controversial arguments in the field of international trade is that protection can actually enhance industrial development by shielding a nascent industry from the intensity of competition with established foreign technologies: the so-called ‘infant industry argument’. Roberto Bonfatti presented a paper that regarded World War I as creating a natural experiment that cut India off from trade with the UK, asking whether this promoted Indian industrial development as a result. More specifically, the paper explores whether regions in India that were more exposed to the negative trade shock with the UK had a greater propensity to increase their manufacturing output. It finds that Indian districts that were exposed to a greater fall in net imports from Britain in 1913-1917 did indeed witness a greater increase in industrial employment as a result. The effect is statistically and economically significant: in the paper’s baseline results, as one moves from the 10th to 90th percentile in exposure to the shock, the share of industrial employment to total population increases, on average, by an extra 12% of the initial value.

Labor Market Distortions, Trade and Development

There is a growing empirical literature arguing that minimum wages do not have adverse employment consequences, challenging conventional wisdom in economics. In turn, minimum wages have been on the rise, both in level and the degree to which they are enforced. The paper presented by Xue Bai argues that findings of apparent positive (or not significantly negative) employment effects from minimum wages may arise from the fact that these studies take a partial-equilibrium approach. Her paper takes a general-equilibrium approach based on the underlying structure of a Heckscher-Ohlin model. Moreover, it introduces firms that are heterogeneous in their productivity levels, and focuses on the selection effects of minimum wages across all sectors. The key feature of her model is that the exit of existing firms increases as a result of an increase in the minimum wage in sectors that have a binding minimum wage. Based on data for China, the paper shows that, as predicted by the model, a binding minimum wage raises product prices, encourages substitution away from labor, though less so for high-skill-intensive and capital-intensive goods, and creates unemployment. Less obviously, it reduces output and exports, especially of the labour-intensive good, despite the price increases. Least obvious is the prediction, also borne out in the data, that selection in the labour-intensive sector becomes stricter, while that in the capital intensive sector becomes weaker.

While rigidities in the labor market can create unemployment, the existence of an informal sector that doesn’t have these rigidities can provide a buffer that helps to absorb adverse shocks to the economy. The paper presented by Gabriel Ulyssea focuses on the informal sector in Brazil where firms do not register with the authorities but do perform legal production, and are therefore invisible to the government. Brazil has a long history of measuring informality through household surveys. Informality provides greater job availability but no employment insurance to workers, thereby creating ambiguous effects on welfare. In this environment, Ulyssea’s paper explores the labor market and welfare effects created by globalization shocks. The framework provides a structural equilibrium model in which counterfactual analysis of the shocks can be performed. A key finding of the paper is that a stricter crackdown on informality would have led to significantly more adverse welfare effects from the globalization shocks that hit Brazil in the early 1990s. Their findings suggest that the informal sector does indeed play the role of shock-absorber in the Brazilian economy.

Political Institutions and Economic Development

Economic institutions are not all that matters in the determination of economic development. An increasingly influential view holds that political institutions are important in the determination of economic institutions and hence economic performance, with particular emphasis on democracy.

Democracy and Economic Development

Marcus Eberhardt presented a paper that explored the robustness of the findings of a recent publication in the Journal of Political Economy by Acemoglu, Naidu, Restrepo and Robinson (ANRR) titled “Democracy Does Cause Growth.” ANRR show that the long-run effects of democratization are a sizeable increase in per capita GDP of 20% or more. Eberhardt’s analysis relaxes two of the key assumptions that ANRR make, that there is a homogeneous parametric relationship between democracy and growth across all the countries in their sample, and that there is an absence of strong cross-sectional correlation. His results indicate that the relationship between democracy and growth is in fact heterogeneous. Specifying instead an alternative empirical approach adopted from the recent panel time series literature that allows for this heterogeneity, he finds that the economic magnitude of democratization on per capita GDP is 10%, thus still substantial but more modest than in the results of ANRR.

A controversial aspect of democracy concerns whether non-nationals have an effect on the outcome of national elections when institutional features are designed to prevent them from doing so. The paper presented by Michele Valsecchi explored whether sanctions imposed on the Russian Federation by 37 other countries in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea had an effect on the election of Vladimir Putin to the position of President of Russia in 2018. As the paper explains, the general intention of sanctions is to cause a policy change by the country against which sanctions are imposed. This might happen because people are made worse off by the sanctions and recognize that a change of policy would cause the sanctions to be lifted, leading the incumbent to respond accordingly. Or it might happen because the sanctions make the incumbent so unpopular that they are voted out of power. Valsecchi’s paper explores the latter possibility. The paper estimates the relationship between the share of countries imposing a sanction in a region’s total trade or GDP on the change in vote share realized by Putin in the election. The surprising finding of the paper is that the higher the share of countries imposing a sanction, the more Putin’s vote share increased! This result supports the widely held opinion amongst economists that sanctions do not achieve their intended outcome of bringing about policy change, and can in fact backfire.

Recent research in political science suggests that the form of government, dictatorship or democracy, may play a role in determining the immigration rights that a country grants. A dictatorship has an incentive to set lax immigration rights to bid down wages on behalf of capitalists, while a democracy has an incentive to set tight immigration restrictions to keep wages high on behalf of workers. But this view struggles to explain why democracies are more inclined to grant naturalization rights, allowing immigrants to become citizens, while dictatorships are not. The paper presented by Ben Zissimos put forward a model that provides an explanation.

The model adapts to an immigration setting a popular argument in economics that the purpose of a trade agreement is to enable the government to tie its hands against lobbying by protectionist pressures from interest groups. The government would want to do this if the short-run compensation from lobbying is not sufficient to compensate it for the long-run distortions created, for which it is not compensated. Drawing on this logic, the model that Zissimos presented could be used to show that the government may be better off committing to an institution that supports immigration in the long term, i.e. naturalization, thereby shutting down lobbying over immigration to some degree. Moreover, the weaker is the government’s bargaining power, the lower is its short-run compensation from lobbying and so the more likely it is to gain from naturalization. Crucially, a government will have less bargaining power vs the lobby if it is a democracy than a dictatorship. The reason is that democracies typically have less bargaining power in an institutional environment where they are also constrained by the rule of law, while dictatorships are not typically so constrained.

Bibliography of Papers Presented with Links Where Available (Presenters’ Names Shown in Bold)

Reshad N. Ahsan, Laura Panza and Yong Song “Atlantic Trade and the Decline of Conflict in Europe: Evidence from 250 Years of Data”

Facundo Albornoz, Irene Brambilla, and Emanuel Ornelas “The Impact of Tariff Hikes on Firm Exports”

Xue Bai, Arpita Chatterjee, Kala Krishna and Hong Ma “Trade and Minimum Wages in General Equilibrium: Theory and Evidence“

Mostafa Beshkar and Ali Shourideh “Optimal Trade Policy with Trade Imbalances“

Roberto Bonfatti and Björn Brey “Trade Disruption, Industrialisation, and the Setting Sun of British Colonial Rule in India“

Oriana Bandiera, with Clare Balboni, Robin Burgess, Maitreesh Ghatak and Anton Heil “Why Do People Stay Poor?“

Francisco Costa, Fabien Forge, Jason Garred and João Paulo Pessoa “Hedging Climate Change: Yield Volatility, Crop Choice and Trade”

Fabrice Defever, José-Daniel Reyes, Alejandro Riaño and Gonzalo Varela “All These Worlds are Yours, Except India: The Effectiveness of Cash Subsidies to Export in Nepal“

David R. DeRemer “Agreements and Disputes over Behind-the-Border Non-Tariff Measures”

Rafael Dix-Carneiro, Pinelopi K. Goldberg, Costas Meghir, and Gabriel Ulyssea “Trade and Informality in the Presence of Labor Market Frictions and Regulations“

Markus Eberhardt “Democracy Does Cause Growth: Comment“

Ferdinand Eibl and Adeel Malik “The Politics of Partial Liberalization: Cronyism and Non-Tariff Protection in Mubarak’s Egypt“

Lisandra Flach, Michael Irlacher, and Florian Unger “Corporate Taxation, Multi-Product Firms, and International Trade“

Atisha Ghosh and Ben Zissimos “The Political Economy of Immigration, Investment, and Naturalization”

Roberg Gold, Julian Hinz, and Michele Valsecchi “To Russia with Love? The Impact of Sanctions on Elections”

Michele Imbruno “Importing under trade policy uncertainty: Evidence from China”

Note that Michele told us his paper had been accepted for publication after submission to the workshop and we were nevertheless happy to keep the paper on the program.

Adam Jakubik and Roberta Piermartini “How WTO Commitments Tame Uncertainty”

Ahmad Lashkaripour and Volodymyr Lugovskyy “Scale Economies and the Structure of Trade and Industrial Policy“

Giovanni Maggi and Ralph Ossa “Are Trade Agreements Good for You?“

Beatriz Manotas-Hidalgo, Fidel Pérez-Sebastián, and Miguel Angel Campo-Bescós “Reexamining the Role of Income Shocks and Ethnic Cleavages on Social Conflict in Africa at the Cell Level“

Devashish Mitra (Syracuse University), Hoang Pham (Syracuse University), Beyza Ural Marchand “Skills and International Trade: Intergenerational Mobility in Vietnam”

Niclas Moneke “Infrastructure and Structural Transformation: Evidence from Ethiopia“

Lena Sheveleva “Minimal Model of Multi-product Firms“

Hâle Utar “Firms and Labor in Times of Violence: Evidence from the Mexican Drug War“

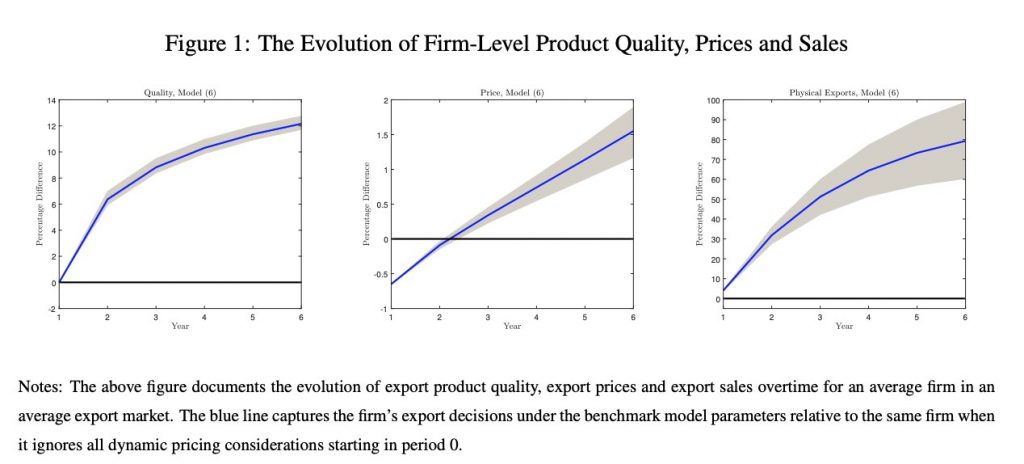

Figure 1 Panel A

Figure 1 Panel A Figure 1 Panel B

Figure 1 Panel B