Sara-Jane Luke

‘Boys in schools want to learn about gender, it matters to them, it’s important in their lives’- Raewyn Connell

It is undeniable that the UK school system is taking steps in the right direction regarding sex, relationship and sexuality education, with health and wellbeing education becoming a mandatory part of the curriculum by 2020. However, even with this progress the curriculum still neglects to educate the nation’s children about a fundamental aspect of human life: Gender. False ideology and misconceptions surrounding gender have been the source of the oppression of women, and LGBTQ+ people for centuries and yet this is a topic that we still fail to treat with appropriate importance within the education system.

- To combat gender inequality

Since the introduction of the contraceptive pill in 1961 gave women more autonomy over their bodies and life choices, there has been great improvement in gender equality. However, gender inequality is still a substantial issue within our society. For example, within the BBC there are no Women in the top ten highest paid presenters and only two in the top twenty. This is something that is also evident in our everyday work environments with the IFS 2016 finding that the hourly wage for women is still 18% lower than men’s on average.

Children internalise the stereotypes that perpetuate this inequality at a very early age.

For example, in the Channel 4 series: The Secret Life of Five Year Olds, in which some of the boys demonstrate a historically held view by boys that they belong to a ‘club’ exclusive of girls and that the girls can only join in if they ‘cook’ for them. This shows enforced gender roles, i.e. that women do the cooking while the men ‘hunt’, from the age of five. This is problematic because not only do the boys have this opinion regarding the domesticated role that women ‘should’ play but this sends the girls the message that they may only join in in this ‘male’ world on the boys’ terms. This demonstrates that whether we are conscious of doing so or not, we are sending children extremely problematic messages. For this reason, it essential that we teach our children of both genders that they have equal value from an early age.

For example, in the Channel 4 series: The Secret Life of Five Year Olds, in which some of the boys demonstrate a historically held view by boys that they belong to a ‘club’ exclusive of girls and that the girls can only join in if they ‘cook’ for them. This shows enforced gender roles, i.e. that women do the cooking while the men ‘hunt’, from the age of five. This is problematic because not only do the boys have this opinion regarding the domesticated role that women ‘should’ play but this sends the girls the message that they may only join in in this ‘male’ world on the boys’ terms. This demonstrates that whether we are conscious of doing so or not, we are sending children extremely problematic messages. For this reason, it essential that we teach our children of both genders that they have equal value from an early age.

- To prevent bullying

Bullying relies on the exploitation of people’s differing attributes. Many young people suffer from poor mental health as a result of discrimination, scrutiny and a lack of comprehensive gender education for young people. For example, 52% of LGBTQ+ young people reported self-harm either recently or in the past compared to 25% of heterosexual non-trans young people.

Gender education leads to a more accepting society where people can feel safe and secure in their own skin. We cannot expect children to be understanding of difference and diversity if we tell them that this diversity does not exist. Until gender is discussed openly and honestly from an early age, children will be fearful and confused about these differences both within themselves and others.

- To enhance children’s self-understanding

Lack of self-understanding leads to a fear of what others perceive us as and an introversion of our views and understanding of others. Encouraging children to experiment with different groups of toys and clothing regardless of gender allows the child to develop understanding and appreciation of differing views and cultures. Although it may be said that it is the job of the parents to decide what their children play with, school is the only place in which we can ensure that every child is given the appropriate tools to navigate our social world. Making this sort of experimentation a compulsory part of the curriculum ensures through policy that self-knowledge is fostered and embraced.

Lack of self-understanding leads to a fear of what others perceive us as and an introversion of our views and understanding of others. Encouraging children to experiment with different groups of toys and clothing regardless of gender allows the child to develop understanding and appreciation of differing views and cultures. Although it may be said that it is the job of the parents to decide what their children play with, school is the only place in which we can ensure that every child is given the appropriate tools to navigate our social world. Making this sort of experimentation a compulsory part of the curriculum ensures through policy that self-knowledge is fostered and embraced.

- To tackle Toxic Masculinity

The danger of society requiring men and consequently boys to prove themselves as strongly masculine is that it steers them towards restricted options. To excel intellectually or to find another physical way to succeed in expressing this ‘masculinity’. This puts restrictive pressure on boys and creates friction between and within the genders. It creates segregation between those who express their masculinity intellectually and those who express their masculinity in a more physical way. This differentiation leads to exclusion of ‘gentle’ academic boys and girls, and a lack of academic confidence and support of the boys who express this physical masculinity.

The danger of society requiring men and consequently boys to prove themselves as strongly masculine is that it steers them towards restricted options. To excel intellectually or to find another physical way to succeed in expressing this ‘masculinity’. This puts restrictive pressure on boys and creates friction between and within the genders. It creates segregation between those who express their masculinity intellectually and those who express their masculinity in a more physical way. This differentiation leads to exclusion of ‘gentle’ academic boys and girls, and a lack of academic confidence and support of the boys who express this physical masculinity.

By teaching boys at a young age that showing emotion and being kind is not a weakness but a strength, we will put them on the path to self-knowledge and healthy relationships.

I hope to have provided in brief four of many reasons for making gender education a compulsory part of the curriculum for children in key stage one (aged 5-7). This is the time to lay the fundamental building blocks for future discussion and healthy development for the individual children and society as a whole.

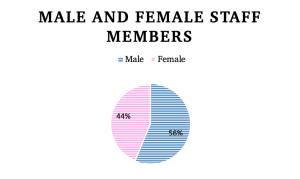

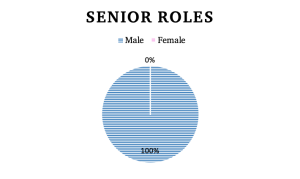

Out of the telesales staff, three are males, with the office manager being male. Out of the six area sales representatives, all are male. Therefore, we are presented with figure 1. Given these observations, you would think that my office is relatively symmetrical in terms of sex distribution. This is not the case, well not in terms of the roles that are performed by each staff member anyway. For example, all seven superior roles are those that the office manager and area sales representatives occupy (figure 2).

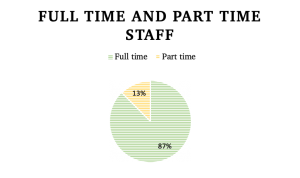

Out of the telesales staff, three are males, with the office manager being male. Out of the six area sales representatives, all are male. Therefore, we are presented with figure 1. Given these observations, you would think that my office is relatively symmetrical in terms of sex distribution. This is not the case, well not in terms of the roles that are performed by each staff member anyway. For example, all seven superior roles are those that the office manager and area sales representatives occupy (figure 2). In figure 3, it is shown that all staff members, excluding two, work full-time.

In figure 3, it is shown that all staff members, excluding two, work full-time.