by Camilla Beghin

Summer 2020, Covid-19 shut the world down. Why not restart dating then? Needless to say, I realised soon that Covid had changed the dating scene. That is when a friend of mine, let’s call him Harry, encouraged me to try online dating. Just before, like some character from a fairytale preparing me for a quest, he told me: “You have to step up your game!” He then informed me that as a white, European man, getting matches is a mission.

Summer 2020, Covid-19 shut the world down. Why not restart dating then? Needless to say, I realised soon that Covid had changed the dating scene. That is when a friend of mine, let’s call him Harry, encouraged me to try online dating. Just before, like some character from a fairytale preparing me for a quest, he told me: “You have to step up your game!” He then informed me that as a white, European man, getting matches is a mission.

Throughout the years, he was not the only man who mentioned to me the difficulties within the online dating world.

Two years later, I realise the complexity of online dating. There are so many hierarchies: between genders, among males and between ethnicities. So, as online dating is increasingly more relevant in the after-pandemic in the UK (Gevers, 2021), I want to present these dynamics.

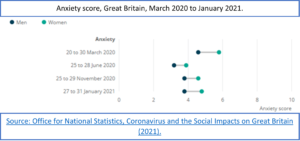

The above figure shows the tendency of online dating use from the start of the pandemic in the UK. The surge in August can be associated with an easing of the restriction imposed by the government, allowing more people to socialise (Gevers, 2021).

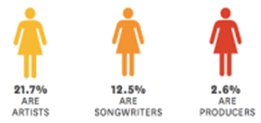

Females at the top

Following Mead’s model of society and gender (1935), it supports a hierarchy that places men as dominant and females as dominated (applicable to most aspects of social life). Online dating seems an exception. Let’s take the case of Tinder, the most used online dating app for my age group (18-29) (Statista, 2022): the data suggests there were 9 men for every woman in 2019. This reverses the traditional power roles. Women have more choice. We stand at the top of the hierarchy deciding the rules. Turns out, Harry is right: men have to step up their game! For a couple of matches he got on Tinder that summer, I would get about 50: I had much more choice.

But do women really have power? I had to step up my game too. How? By conforming to the traditional ways of “doing gender” through gender performance (see Messner, 2000; West and Zimmerman, 1987). Both Harry and I would choose the best pictures, select the best information about us. Some people go further. They use deception to perform gender to appear attractive (see Ankee and Yazdanifard, 2015). So yes, women have more power, but within the traditional gender performance boundaries.

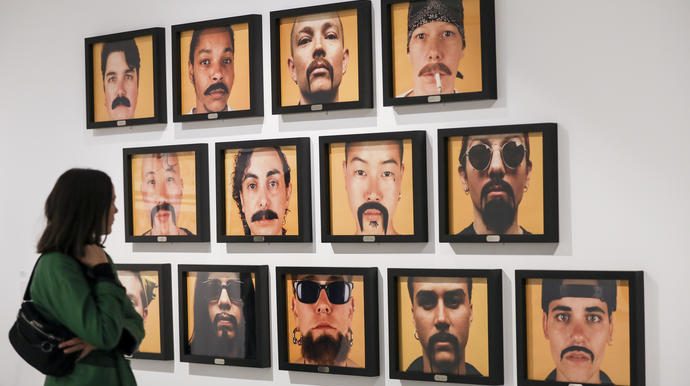

Fessler, 2017

Men’s double hierarchy

Harry did not realise that he was also part of a male hierarchy. Being at its top means getting more matches. This is something another friend, let’s call him Tom, told me: in Exeter he has to compete with rugby lads and various sporty men; he struggles to stand out. After talking with various girls, I realised this fits the male hierarchy suggested by Connell and Messerschmidt (2005). We have 3 main types of men, and intersections of them:

• Hegemonic males: physically active and intellectually or socially powerful.

• Complicit males: receiving benefits of patriarchy.

• Subordinated males: minorities, often part of LGBTQ+.

I can see similar patterns on Tinder. Men try to prove their level of masculinity between hegemonic and complicit (as I participated in heterosexual dating, I cannot speak for the last group). So they show off sport abilities, drinking habits, and their degrees as opposed to simply their hobbies and passions.

This revealed men have a double struggle: they have less power than women and they compete to come across as more desirable by performing the “best” masculinity.

Intersectionality with ethnicity

We cannot only consider gender in online dating: ethnicity is equally important. In their study in the USA, Lin and Lundquist (2013) prove how ethnicity plays a strong part in dating selection. They were analysing the intersection between race, education and gender to understand tendencies in online dating. So, they discovered a tendency for women to respond to men of similar ethnicity or higher, whilst non-black man to ignore black women. This complicated the hierarchy adding other ladders.

I experience how my Italian origin was perceived as more “exotic”, so more attractive by British men. As a white, Italian woman I used it to step up my game, but I am conscious that some women’s ethnicity might be a factor damaging their chances.

So, ethnicity complicates the previous hierarchies. Some ethnicities (usually white) are considered advantaged compared to others. Also, within the same ethnicity, there is a tendency to reproduce gender hierarchies. Men over women.

My conclusions

• Heterosexual online dating has different hierarchies: between women and men, among men, between ethnicities.

• Both genders “perform gender”

• Ethnicity plays an important role: complicating the hierarchies.

As a white, “exotic”, woman it worked for me. Was I in a different position in the hierarchy, I would be wondering just as Tom: why the heck am I doing this to myself?

Bibliography:

Ankee, A.W. and Yazdanifard, R (2015) The Review of the Ugly Truth and Negative Aspects of Online Dating, Global Journal of Management and Business Research: E-Marketing. 15(4).

Chen, O. (2022) You are more than Tinder. online Available at: https://ozchen.com/you-are-more-than-tinder/Accessed: 15 March 2022.

Cherednichenko, S. (2020) Top 10 Dating Apps in 2020, mobindustry. online Available at: https://medium.com/mobindustry/top-10-dating-apps-in-2020-1f35b0c624b6 Accessed: 15 March 2022.

Connell, R.W. and Messerschmidt, J.W. (2005) Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept, Gender & Society. 19(6): 829-859.

Fessler, L. (2017) Tinder now shows its premium customers who likes them – even when the feeling’s not mutual., Quartz. online Available at: https://qz.com/1064995/tinder-gold-premium-membership-likes-me-function-can-i-see-who-already-swiped-right-on-me-on-tinder/ Accessed: 15 March 2022

Gevers, A. (2021) Online Dating in Europe, ComScore. online Available at: https://www.comscore.com/Insights/Blog/Online-Dating-in-Europe Accessed: 4 March 2022.

Lin, K. and Lundquist, J. (2013) Mate Selection in Cyberspace: The Intersection of Race, Gender, and Education, American Journal of Sociology. 119(1): 183.215.

Mead, M. (1935) Sex and temperament in three primitive societies. New York: William Morrow.

Messner, M.A. (2000) Barbie Girls Versus Sea Monsters: Children Constructing Gender, Gender & Society. 14(6): 765-784.

Statista (2022) Share of individuals who were current or past users of online dating sites and apps in the United Kingdom (UK) in June 2017, by age group, Statista. online Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/714211/online-dating-site-and-app-usage-in-the-united-kingdom-by-age-group/ Accessed: 5 March 2022.

West, C. and Zimmerman, D.H. (1987) Doing Gender, Gender & Society. 1(2): 125-151.

As a male, it is strange for people to hear me say that I am a feminist. Women are curious about the reasons behind this, while men think I am betraying men or have been brainwashed by feminist theory. This is a sad result, because in my view the feminist movement is an anti-authoritarian movement, and in post-modern society people often break with authority to construct new ideas, new isms. So why did men lose out to feminism? The result is obvious: an unwillingness to give up privilege. When I was a child, I often wondered about the traditional Chinese family model. I couldn’t understand why my father smoked in the house without regard for the feelings of others, why the men in the family didn’t fulfil their responsibilities as husbands but the women didn’t dare to run away, and so on, some of the absurd things that we were used to but that I started to think about when I was very young. I was later introduced to feminism, the most famous of which in China is Beauvoir and her book The Second Sex. The popularity of Beauvoir in China could not have been achieved without Li Yinhe, who brought some of Beauvoir’s ideas to China and made them very popular. Of course, Beauvoir’s past with Sartre is also a subject of great interest to the Chinese. Her mode of living with Sartre has, I think, in a way changed the way many people view marriage. As I read the book, I was struck by how many of my thoughts as a young child were echoed in the book. Some of the ideas or examples in the book were repeated over and over again in reality.

As a male, it is strange for people to hear me say that I am a feminist. Women are curious about the reasons behind this, while men think I am betraying men or have been brainwashed by feminist theory. This is a sad result, because in my view the feminist movement is an anti-authoritarian movement, and in post-modern society people often break with authority to construct new ideas, new isms. So why did men lose out to feminism? The result is obvious: an unwillingness to give up privilege. When I was a child, I often wondered about the traditional Chinese family model. I couldn’t understand why my father smoked in the house without regard for the feelings of others, why the men in the family didn’t fulfil their responsibilities as husbands but the women didn’t dare to run away, and so on, some of the absurd things that we were used to but that I started to think about when I was very young. I was later introduced to feminism, the most famous of which in China is Beauvoir and her book The Second Sex. The popularity of Beauvoir in China could not have been achieved without Li Yinhe, who brought some of Beauvoir’s ideas to China and made them very popular. Of course, Beauvoir’s past with Sartre is also a subject of great interest to the Chinese. Her mode of living with Sartre has, I think, in a way changed the way many people view marriage. As I read the book, I was struck by how many of my thoughts as a young child were echoed in the book. Some of the ideas or examples in the book were repeated over and over again in reality.

“Revenge dressing” was made famous by Princess Diana in 1994. Her jaw dropping “revenge dress” was worn at the Serpentine Gallery. She wanted to hit back at Prince Charles’ infidelity and show him what he was missing.

“Revenge dressing” was made famous by Princess Diana in 1994. Her jaw dropping “revenge dress” was worn at the Serpentine Gallery. She wanted to hit back at Prince Charles’ infidelity and show him what he was missing. Following CPB-London’s recent ‘imagine a’ campaign:

Following CPB-London’s recent ‘imagine a’ campaign: The association between masculinity and guitars is a relatively recent phenomenon. Originally, the guitar was a paradigmatic feminine instrument. In 1783, Carl Junker named the guitar’s predecessors

The association between masculinity and guitars is a relatively recent phenomenon. Originally, the guitar was a paradigmatic feminine instrument. In 1783, Carl Junker named the guitar’s predecessors So, when did guitar’s feminine-status decline? Pinpointing a date here is difficult. Whilst the well-known Delta-Blues players of the early 20th Century are all men,

So, when did guitar’s feminine-status decline? Pinpointing a date here is difficult. Whilst the well-known Delta-Blues players of the early 20th Century are all men, Strohm points to the invention of the electric guitar (Weinstein, 2013). This makes sense: before amplification, the guitarist had the quiet role at the back of the Big-Band. Once amplified, the guitar could take the lead role (ibid).

Strohm points to the invention of the electric guitar (Weinstein, 2013). This makes sense: before amplification, the guitarist had the quiet role at the back of the Big-Band. Once amplified, the guitar could take the lead role (ibid). Enter the men. Amplification permits distortion: the aggressive sound of rock. Here we start to see the masculine paradigms work their way in. Then comes the virtuoso; the fiery and phallic displays in the late 1960s.

Enter the men. Amplification permits distortion: the aggressive sound of rock. Here we start to see the masculine paradigms work their way in. Then comes the virtuoso; the fiery and phallic displays in the late 1960s. Firstly, once the guitar had been made masculine, the unspoken rule of ‘standard’ coming to mean ‘masculine’ instantiated itself.

Firstly, once the guitar had been made masculine, the unspoken rule of ‘standard’ coming to mean ‘masculine’ instantiated itself. Against the masculine-as-standard backdrop, Wet-Leg’s deviation from masculine-styles of guitar-playing is viewed as a deviation from ‘good’ guitar-playing. One video that centres Wet-Leg’s guitar-style is riddled with comments expressing their disgust for it. So Wet-Leg refuse to play guitar like men. And thus fuels the fire of ‘industry plant’ accusations.

Against the masculine-as-standard backdrop, Wet-Leg’s deviation from masculine-styles of guitar-playing is viewed as a deviation from ‘good’ guitar-playing. One video that centres Wet-Leg’s guitar-style is riddled with comments expressing their disgust for it. So Wet-Leg refuse to play guitar like men. And thus fuels the fire of ‘industry plant’ accusations.

Heavy drinking at university is considered to be a behaviour that displays elements of hegemonic masculinity (Dempster, 2009). Exeter rugby boys commonly engage in heavy drinking, especially during their Wednesday sports socials. They show off their masculinity by proving that they can drink multiple pints or by drinking a pint as quickly as they can. At socials, they are constantly forced to drink. I was very surprised when my friend who is in the Exeter Rugby Society told me that he drank 22 pints within the space of 2 hours! Also, freshers (first years), as part of their initiation, are forced to engage in acts that highlight their ability to withstand pain and embarrassment. These acts include getting naked and drinking or eating things like cat food (Dempster, 2009). Quite frankly, you do not even want to know what one boy drank this year in order to earn the role of the mascot at varsity.

Heavy drinking at university is considered to be a behaviour that displays elements of hegemonic masculinity (Dempster, 2009). Exeter rugby boys commonly engage in heavy drinking, especially during their Wednesday sports socials. They show off their masculinity by proving that they can drink multiple pints or by drinking a pint as quickly as they can. At socials, they are constantly forced to drink. I was very surprised when my friend who is in the Exeter Rugby Society told me that he drank 22 pints within the space of 2 hours! Also, freshers (first years), as part of their initiation, are forced to engage in acts that highlight their ability to withstand pain and embarrassment. These acts include getting naked and drinking or eating things like cat food (Dempster, 2009). Quite frankly, you do not even want to know what one boy drank this year in order to earn the role of the mascot at varsity.

It seems unlikely that they just didn’t see the dirt. When participants in one experimental study were shown pictures of an untidy room, there were no gendered discrepancies in perception; both men and women evaluated the level of mess and degree of urgency to clean it similarly. However, when the gender of the occupant of the messy room was known, moral judgments emerged, with female room dwellers held to a higher standard than men (Thébaud et al., 2019).

It seems unlikely that they just didn’t see the dirt. When participants in one experimental study were shown pictures of an untidy room, there were no gendered discrepancies in perception; both men and women evaluated the level of mess and degree of urgency to clean it similarly. However, when the gender of the occupant of the messy room was known, moral judgments emerged, with female room dwellers held to a higher standard than men (Thébaud et al., 2019). However, while Goffman sees these performances as optional, West and Zimmerman disagree. They view that people are made ‘accountable’ for their performances in their socially approved sex categories of ‘women’ or ‘men’. Through consensus of expected, ‘appropriate’ behaviour, people are kept in order. In the patriarchies of the West, men top the hierarchy. So, while gender is enacted at an individual level, these interactions are institutionally inscribed. As a result, apparent ‘essential’ differences continue to segregate women and men in normative ways. The gendered division of labour appears to be normal and natural. So, the fact that women’s work is never done is accepted, even useful, in maintaining the status quo.

However, while Goffman sees these performances as optional, West and Zimmerman disagree. They view that people are made ‘accountable’ for their performances in their socially approved sex categories of ‘women’ or ‘men’. Through consensus of expected, ‘appropriate’ behaviour, people are kept in order. In the patriarchies of the West, men top the hierarchy. So, while gender is enacted at an individual level, these interactions are institutionally inscribed. As a result, apparent ‘essential’ differences continue to segregate women and men in normative ways. The gendered division of labour appears to be normal and natural. So, the fact that women’s work is never done is accepted, even useful, in maintaining the status quo.