“The term ‘sex’ should be understood as an individual’s biological make-up and ‘gender’ as culturally learnt and enacted by individuals”. (Oakley, 1985)

If you were to picture in your mind, a typical office setting, what would it look like? I bet you pictured something a little like this: several desks with computers on and staff members sat at them, as well as a few separate offices for managerial staff. Having imagined this, what sex are the staff members sat at the desks and the managerial staff in separate offices? If you imagined the desk staff as female and managerial staff as male, you imagined correctly, or at least how I expected you to anyway. This is something Blackburn et al (2002) deem as vertical segregation, as a hierarchal arrangement within an occupational setting, particularly in the case of the sexes.

It is precisely for this reason that I invited you to engage in the previous hypothetical situation, as it is one that is similar to my own workplace; the place that I work weekly alongside my University studies and on a full-time basis during holidays. I have worked at this Wholesaler and family-run company for nearly five years and have always been consciously aware of how the company is segregated on the basis of sex, but only now have I began wondering why this segregation has persisted.

For the purpose of my case study, we are going to focus on the telesales and area sales representative staff of the company. In the telesales office, there are ten individuals; one manager and nine whose responsibility it is to deal with customer queries and process orders by answering and making phone calls. The responsibilities of the six area sales representatives involves the managing of customers and acquiring more business, with the office being at their disposal to use.

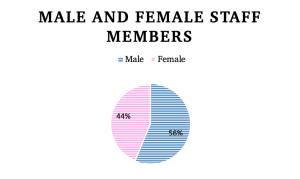

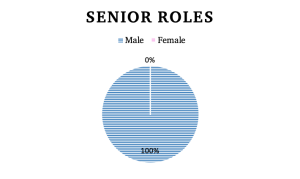

Out of the telesales staff, three are males, with the office manager being male. Out of the six area sales representatives, all are male. Therefore, we are presented with figure 1. Given these observations, you would think that my office is relatively symmetrical in terms of sex distribution. This is not the case, well not in terms of the roles that are performed by each staff member anyway. For example, all seven superior roles are those that the office manager and area sales representatives occupy (figure 2).

Out of the telesales staff, three are males, with the office manager being male. Out of the six area sales representatives, all are male. Therefore, we are presented with figure 1. Given these observations, you would think that my office is relatively symmetrical in terms of sex distribution. This is not the case, well not in terms of the roles that are performed by each staff member anyway. For example, all seven superior roles are those that the office manager and area sales representatives occupy (figure 2).

Why is it then that my workplace assigns females in different positions than their male counterparts? I have a few suggestions for you to ponder your thoughts upon.

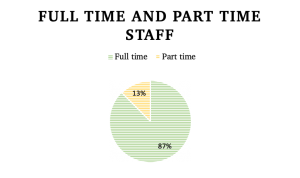

In figure 3, it is shown that all staff members, excluding two, work full-time.

In figure 3, it is shown that all staff members, excluding two, work full-time.

Ironically, both these individuals, one male and one female, occupy the more passive roles within the company. Often, it is argued that women occupy more part-time roles than men and thus accounts as to why so few have managerial roles within the workplace.

On the contrary, Hakim (1995) argues that part-time roles are accredited and account for individuals such as students, not just exclusively women. This example shows that if women occupy part-time roles, there are often explanations as to why they do – being a student myself is living proof. Although, this is not to say that all women have the same experience.

I will now focus on a broader and more prevalent issue: patriarchal society. This society inevitably generates norms and values that individuals adhere to, which remain engrained into their consciousnesses. Though progress has been made, the fact is that men continue to be viewed as the superior sex, which applies to my workplace, given the lack of female authoritative figures within it. Building upon this view, West and Zimmerman (1987) describe ‘gender’ as a set of normative conceptions of appropriate attitudes and activities, i.e. we are likely to view traits of leadership and confidence as qualities that men tend to adopt; to be empathetic and nurturing on the other hand, are qualities that we would associate with women. Despite both sexes having the capacity to adopt both sets of traits, the first are deemed as inherently male and more valuable within the workplace. From this, gender can be seen as constructing an individuals’ position in the social structure (West and Fenstermaker, 1995).

Overall, one may argue that certain individuals genuinely possess more desirable attributes that a position requires, and this may very well be the case as to why men and women differentiate in their job prospects and positions. However, I do not believe this to be the case in my workplace. Without any disrespect intended, but the females, including myself, are just as capable of performing the senior roles that the males occupy.

At the end of the day, it is about being more accepting and willing of individuals by not limiting them to positions based on their sex or their ‘gendered’ qualities.

*NB: if you are interested in the issue of sex segregation, look at this report by the European Institute for Gender Equality: http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-14624-2017-ADD-2/en/pdf.

Photo by rawpixel.com from Pexels

Emily Atkins

References

Blackburn, R., et al. (2002) Explaining gender segregation. British Journal of Sociology. 53(4), p513-36

Hakim, C. (1995) Five Feminist Myths about Women’s Employment. The British Journal of Sociology. 46(3), p429-55

Oakley, A (1985) Sex, Gender and Society. Gower: Maurice Temple Smith

West, C., Fenstermaker, S. (1995) Doing Difference. Gender & Society. 9(1), p8-37

West, C., Zimmerman, D. (1987) Doing Gender. Gender and Society. 1(2), p125-51.