by Ellie Gibb

Ditch the joggers, switch off the X-BOX, put down the pint and slap on some lippy. Is that how you do it?

Is it just me or did living, working and studying from home make me more “laddish”? And living with boys throughout lockdown did not help!

Stay at Home De-Feminised Fashion.

Fashion has long been a product of the social climate. Nowhere has this been more apparent than during COVID-19. The pandemic has opened the market for a new stay at home fashion. Never has loungewear, jogging bottoms and pyjamas been so popular.

According to City A.M. – London’s most-read financial and business newspaper – In 2020, loungewear sales rose 1,303%.

Every day I was noticing a blurring between my feminine and masculine side. I had always been a bit of a tomboy and embraced gender-bending practices. Yet when I was stuck inside with boys, I was violating these gendered norms even more. This act of “Garfinkeling”, whereby I was undoing gendered expectations in the privacy of my home was empowering and relaxing.

At the time I was a woman in a man’s world, literally!

What about when lockdown ends…is this still acceptable to act like this?

Consciously Reclaiming Femininity.

When “freedom day” came on May 17th 2021, I asked myself have I forgotten how to be a woman? And how do I “do” gender properly?

I had spent months inside gaming, wearing pyjamas and dragging myself out of bed to the desk.

I had no care in the world surrounding what I was wearing. I did not need to stress about looks in my own home. My housemates were used to my sloppy side and so was I.

For the first time in my life there was zero anxiety about what to wear. What was expected of me, or what I was supposed to be conforming to.

I was not alone here as in 2020, clothes sales slumped 25.1% as no one needed new or fancy clothes (see below).

Your clothes say a lot about you. They are status symbols. They define you and they are a significant part of your identity.

I had not been out in months. So now I need to use my wardrobe to reclaim my femininity! I wanted to “dress like a girl” and be glamorous for the first time in months.

Now was the time to impress and put on the best and most authentic performance. Let’s show the world that I can be feminine!

This initial moment was huge and of heightened importance. It represented a “magnified moment” in my lifetime. Want to learn more about moments like these? Check out this link: ‘Barbie Girls Versus Sea Monsters’.

You are Actually Going Out…It is NOT on Zoom!

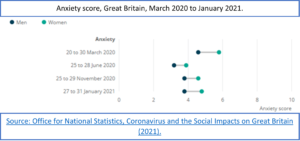

After comfort dressing for months in the confines of my home, fashion had been the last thing on my mind. In fact, fashion had been non-existent for a long period of time. My wardrobe remained untouched. As a result, the anticipation of freedom created a sense of anxiety, specifically amongst women (see below).

I don’t usually wear high heels, dresses or make-up…but I felt the need to. I was left asking ‘Why was this? Why do I have the desire to “dress myself up”?’

Yet everyone was doing it as in 2021 online searches for high heels and dresses were up by 197% and 176%.

Post-Lockdown Revenge Dressing.

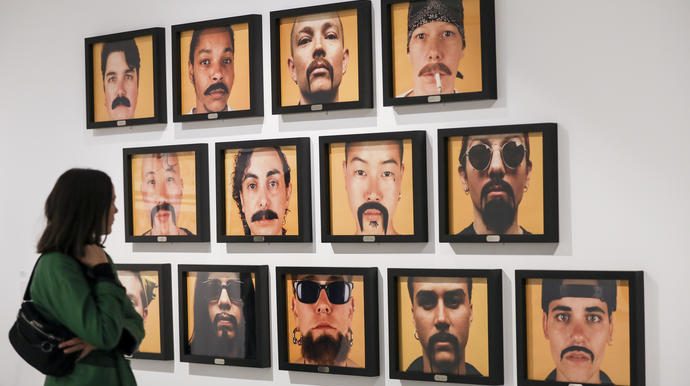

“Revenge dressing” was made famous by Princess Diana in 1994. Her jaw dropping “revenge dress” was worn at the Serpentine Gallery. She wanted to hit back at Prince Charles’ infidelity and show him what he was missing.

“Revenge dressing” was made famous by Princess Diana in 1994. Her jaw dropping “revenge dress” was worn at the Serpentine Gallery. She wanted to hit back at Prince Charles’ infidelity and show him what he was missing.

Yet, a new trend of revenge dressing was emerging due to COVID-19 restrictions being lifted. The pandemic has given a whole new meaning to revenge dressing. Post-lockdown statement outfits were bolder, brighter and better than ever before.

After all the talk of freedom day, my femininity fears peaked. I had to be the best and most glamorous version of me.

Everyone began treating the walk into Turtle Bay for bottomless brunch as their first red carpet appearance!

But this left me asking… am I now over-“doing” gender?

Most importantly, I concluded that no I am not overdoing gender. I am a woman reconstructing gender, transforming femininity and hybridizing my identity. I am in control of who I want to be. I can reclaim my femininity by dressing to impress whilst sipping my cosmopolitan. But then I can return home to my jogging bottoms, my pint and my home comforts.

Goodbye lounge pants…for now!

Further Readings:

Evans, C. & Thornton, M. (1991). ‘Fashion, Representation, Femininity’, Feminist Review, 38(1), 48-66.

Muse (2020). 2020 Fashion: A Year in Review. Muse. [online]. Accessed 4 May 2022. <https://www.muse-magazine.com/2020-fashion-a-year-in-review/>

Pomerantz, S. (2008). Girls, Style, and School Identities: Dressing the Part. New York & Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

West, C. & Zimmerman, D.H. (1987). ‘Doing Gender’, Gender & Society, 1(2), 125-151.

Woodward, S. (2007). Why Women Wear What They Wear. Oxford & New York: Berg Publishers.

It seems unlikely that they just didn’t see the dirt. When participants in one experimental study were shown pictures of an untidy room, there were no gendered discrepancies in perception; both men and women evaluated the level of mess and degree of urgency to clean it similarly. However, when the gender of the occupant of the messy room was known, moral judgments emerged, with female room dwellers held to a higher standard than men (Thébaud et al., 2019).

It seems unlikely that they just didn’t see the dirt. When participants in one experimental study were shown pictures of an untidy room, there were no gendered discrepancies in perception; both men and women evaluated the level of mess and degree of urgency to clean it similarly. However, when the gender of the occupant of the messy room was known, moral judgments emerged, with female room dwellers held to a higher standard than men (Thébaud et al., 2019). However, while Goffman sees these performances as optional, West and Zimmerman disagree. They view that people are made ‘accountable’ for their performances in their socially approved sex categories of ‘women’ or ‘men’. Through consensus of expected, ‘appropriate’ behaviour, people are kept in order. In the patriarchies of the West, men top the hierarchy. So, while gender is enacted at an individual level, these interactions are institutionally inscribed. As a result, apparent ‘essential’ differences continue to segregate women and men in normative ways. The gendered division of labour appears to be normal and natural. So, the fact that women’s work is never done is accepted, even useful, in maintaining the status quo.

However, while Goffman sees these performances as optional, West and Zimmerman disagree. They view that people are made ‘accountable’ for their performances in their socially approved sex categories of ‘women’ or ‘men’. Through consensus of expected, ‘appropriate’ behaviour, people are kept in order. In the patriarchies of the West, men top the hierarchy. So, while gender is enacted at an individual level, these interactions are institutionally inscribed. As a result, apparent ‘essential’ differences continue to segregate women and men in normative ways. The gendered division of labour appears to be normal and natural. So, the fact that women’s work is never done is accepted, even useful, in maintaining the status quo.