by Stephanie Pang

Music is seen as an expressive tool where individuals can express their emotions. We often use music for many different purposes e.g. aesthetic appreciation or religious worship. However, music is often a battlefield for gender and inequality issues. Gender stereotyping is not a new phenomenon in music. During the 1980s, the majority of women in music videos were dressed sexily (Gow, 1996) while men are seen as masculine figures and carry hegemonic masculinity.

How Males are portrayed in the songs sung by artists

When listening to music, especially songs sang by female singers, it comes as un surprising that men are portrayed as having all the power. The lyrics “I’ll be a fearless leader and I’d be an alpha type’’ (The Man, Taylor Swift), shows that the image of a top manager in society includes a successful man with a strong masculine presence (Acker, 1990). Messner (2000) supported this view stating that men usually hold position e.g. head coach and assistant coach.

Male are also seen as more privileged than females, as they are usually ‘’ranking in dollars, and getting bitches and models’’ (The man, Taylor Swift). This shows that men are like free spirit animals who constantly search for dreams and living the best of their life (Hyden & McCandless ,1983). And, lyrics ‘I’d be just like Leo in Saint Tropez’ (The Man, Taylor Swift) shows that men are like playboys, and Leonardo DiCaprio (fun fact… Leo has a reputation for flirting with different girls, he always takes his girl friends to have fun in Saint Tropez).

Aside from that, men are portrayed as capable of breaking women’s hearts (shame on them….). This is demonstrated in lyrics “How’s your heart after breaking mine?” (Taylor Swift, Mr. Perfectly Fine), the female singer was devastated after being left by a guy. Similarly, another lyric ‘’Pretends he doesn’t know that he’s the reason why you’re drowning….’’ (Taylor Swift, ‘I know you were trouble) conveys the same message. Men being a heartbreaker can be linked to Click and Kramer (2007)’s view that women are perceived to be the ones who constantly have their hearts broken and wish for shooting stars.

How females are portrayed in the songs

If men are usually seen as powerful and masculine? Does that mean women are being seen to having the same characteristics as well??

Well… the answer is probably not. Women are typically portrayed as fragile and weak in songs sung by female singers, as they tend to break down more than men after a relationship ends. This is evident in lyrics ‘Everything that I do reminds me of you, and the clothes you left, they smell just like you’ (Avril Lavigne, when you’re gone). This showed that women were unable to let go of the men and she still believes that the clothes he left smelled like him. Therefore, women are seen as weak and needy (Lisara ,2014).

Other than that, in songs sung by male singers, women are viewed as objects that are constantly being view by men. Sexual objectification occurred through body representation e.g. sexy clothing, body parts (Flynn et al, 2016). This can be seen in lyrics, ‘’Missing more than just your body’’ (Justin Bieber, sorry), ’Everyone else in the room can see it, everyone else but you’’ (One Direction’s What makes you beautiful). These lyrics have shown that man has missed the body of the female he is speaking of ,and it also indicates that a woman’s body is still meant to be touched, even if the man doesn’t deserve it due to his mistakes. Once again, female is being seen as object more than male artists (Flynn et al, 2016).

However, women are not always seen to be portrayed as weak and sexy figures. Songs that are mostly sung by female artists themselves try to fight against marginalization and push for equal rights as well as empowering women (Nwabueze, 2019). Lyrics ‘’I don’t need a man to be holding me too tight’ (Kesha, women) ‘’She’s on top of the world, hottest of the hottest girls’’ (Alicia Keys, Girl on fire) showed that women can live a better live by themselves. This is in consistent with Nwabueze (2019)’s findings that women are seen to be able to rule and bring positive changes to the world. Yet, we can also argue that only songs sung by female artists are able to portrayed woman in a positive way.

To our future☺

Men and women are portrayed differently as we live in a world where certain activities are classified as masculine or feminine (West & Zimmerman, 1987). Therefore, we can see that gender is socially scripted and that men and women must perform a set of performances in order to fit into society.

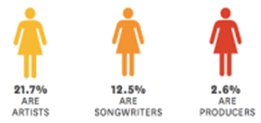

I think it is crucial for us to achieve gender inequality in our society as young adults always listens to pop music. Music will influence their perceptions of relationship, sex and gender roles. As a result, the music industry has a big impact on gender construction. To achieve gender equality, I believe more female composers and singers as well as more positive lyrics about women are needed.

(life is not only about competition; it is also about collaboration between men and women, therefore, men and women must be treated equally)

Reference:

Acker. J (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of Gendered organization, Gender & Society, 4(2), pp.139-158,

https://doi.org/10.1177/089124390004002002

Click. A. M & Kramer. W. M (2007) Reflections on a century of living: gendered differences in mainstream popular songs, Popular Communication, 5(4), pp.241-262,

https://doi.org/10.1080/15405700701608915

Flynn. A. M & Craig. M. C & Anderson. N. C & Holody. J. K (2016), objectification in popular music lyrics: An examination of gender and genre differences, Sex roles, 75, pp. 164-176, DOI 10.1007/s11199-016-0592-3

Gow. J (2009). Reconsidering gender roles on MTV: Depictions in the most popular music videos of the early 1990s, Communication reports, 9(2), pp. 151-161, DOI: 10.1080/08934219609367647

Hyden. C & McCandless. J (1983). Men and women as portrayed in the lyrics of contemporary music, Popular music & Society, 9(2), pp.19-26, DOI: 10.1080/03007768308591210

Lisara. A (2014). The Portryal of Women in Katy Perry’s selected song lyrics, Passage, 2(2), pp.61- 68, Available at: file:///Users/pangwingtakstephanie/Downloads/21156-47562-1-PB%20(2).pdf (Accessed: 18 March)

Messner. A. M (2000). Barbie girls versus sea monsters, children constructing gender, Gender & Society, 14(6), pp.765-784, Available at:

https://vle.exeter.ac.uk/pluginfile.php/2414056/mod_resource/content/1/Barbiegirlsvsseamonsters.pdf (Accessed 14 February)

Nwabueze. C (2009). Pop Music, literature and gender: perceptions of womanhood in Grande’s ‘’God is a woman’’ and Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Litinfinite Journal, pp.23-33, Available at :10.47365/litinfinite.1.1.2019.23-33 (Accessed 15 March)

West. C & Zimmerman. H.D (1987). Doing Gender, Gender and Society, 1(2), pp. 125-151, Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/189945 (Accessed 7 March 2022)

Following CPB-London’s recent ‘imagine a’ campaign:

Following CPB-London’s recent ‘imagine a’ campaign: The association between masculinity and guitars is a relatively recent phenomenon. Originally, the guitar was a paradigmatic feminine instrument. In 1783, Carl Junker named the guitar’s predecessors

The association between masculinity and guitars is a relatively recent phenomenon. Originally, the guitar was a paradigmatic feminine instrument. In 1783, Carl Junker named the guitar’s predecessors So, when did guitar’s feminine-status decline? Pinpointing a date here is difficult. Whilst the well-known Delta-Blues players of the early 20th Century are all men,

So, when did guitar’s feminine-status decline? Pinpointing a date here is difficult. Whilst the well-known Delta-Blues players of the early 20th Century are all men, Strohm points to the invention of the electric guitar (Weinstein, 2013). This makes sense: before amplification, the guitarist had the quiet role at the back of the Big-Band. Once amplified, the guitar could take the lead role (ibid).

Strohm points to the invention of the electric guitar (Weinstein, 2013). This makes sense: before amplification, the guitarist had the quiet role at the back of the Big-Band. Once amplified, the guitar could take the lead role (ibid). Enter the men. Amplification permits distortion: the aggressive sound of rock. Here we start to see the masculine paradigms work their way in. Then comes the virtuoso; the fiery and phallic displays in the late 1960s.

Enter the men. Amplification permits distortion: the aggressive sound of rock. Here we start to see the masculine paradigms work their way in. Then comes the virtuoso; the fiery and phallic displays in the late 1960s. Firstly, once the guitar had been made masculine, the unspoken rule of ‘standard’ coming to mean ‘masculine’ instantiated itself.

Firstly, once the guitar had been made masculine, the unspoken rule of ‘standard’ coming to mean ‘masculine’ instantiated itself. Against the masculine-as-standard backdrop, Wet-Leg’s deviation from masculine-styles of guitar-playing is viewed as a deviation from ‘good’ guitar-playing. One video that centres Wet-Leg’s guitar-style is riddled with comments expressing their disgust for it. So Wet-Leg refuse to play guitar like men. And thus fuels the fire of ‘industry plant’ accusations.

Against the masculine-as-standard backdrop, Wet-Leg’s deviation from masculine-styles of guitar-playing is viewed as a deviation from ‘good’ guitar-playing. One video that centres Wet-Leg’s guitar-style is riddled with comments expressing their disgust for it. So Wet-Leg refuse to play guitar like men. And thus fuels the fire of ‘industry plant’ accusations.

Heavy drinking at university is considered to be a behaviour that displays elements of hegemonic masculinity (Dempster, 2009). Exeter rugby boys commonly engage in heavy drinking, especially during their Wednesday sports socials. They show off their masculinity by proving that they can drink multiple pints or by drinking a pint as quickly as they can. At socials, they are constantly forced to drink. I was very surprised when my friend who is in the Exeter Rugby Society told me that he drank 22 pints within the space of 2 hours! Also, freshers (first years), as part of their initiation, are forced to engage in acts that highlight their ability to withstand pain and embarrassment. These acts include getting naked and drinking or eating things like cat food (Dempster, 2009). Quite frankly, you do not even want to know what one boy drank this year in order to earn the role of the mascot at varsity.

Heavy drinking at university is considered to be a behaviour that displays elements of hegemonic masculinity (Dempster, 2009). Exeter rugby boys commonly engage in heavy drinking, especially during their Wednesday sports socials. They show off their masculinity by proving that they can drink multiple pints or by drinking a pint as quickly as they can. At socials, they are constantly forced to drink. I was very surprised when my friend who is in the Exeter Rugby Society told me that he drank 22 pints within the space of 2 hours! Also, freshers (first years), as part of their initiation, are forced to engage in acts that highlight their ability to withstand pain and embarrassment. These acts include getting naked and drinking or eating things like cat food (Dempster, 2009). Quite frankly, you do not even want to know what one boy drank this year in order to earn the role of the mascot at varsity.

Finally, if you are struggling with any issue which you think is because of bias, don’t hesitate to say it. Remaining in silence cannot change you or the social situation. If you know someone who is suffering from any social issue, please listen to the person’s voice. Ignoring what marginalised people have to say is the same as discriminating them. Let’s take action to change from a ‘gay or Asian man’ issue to a ‘gay and Asian man’ issue and to make the invisible intersections visible!

Finally, if you are struggling with any issue which you think is because of bias, don’t hesitate to say it. Remaining in silence cannot change you or the social situation. If you know someone who is suffering from any social issue, please listen to the person’s voice. Ignoring what marginalised people have to say is the same as discriminating them. Let’s take action to change from a ‘gay or Asian man’ issue to a ‘gay and Asian man’ issue and to make the invisible intersections visible!

I found this to be a charming picture book. It tells the story of young Julian who, after seeing three women dressed up on the subway one day, creates himself a fabulous mermaid costume.

I found this to be a charming picture book. It tells the story of young Julian who, after seeing three women dressed up on the subway one day, creates himself a fabulous mermaid costume.

A great book honouring 25 amazing women throughout history. Featuring politicians, athletes, scientists, artists and more, I found this book inspiring and really champions the idea that any young girl can become whatever they want to be.

A great book honouring 25 amazing women throughout history. Featuring politicians, athletes, scientists, artists and more, I found this book inspiring and really champions the idea that any young girl can become whatever they want to be.

For example, in the Channel 4 series: The Secret Life of Five Year Olds, in which some of the boys demonstrate a historically held view by boys that they belong to a ‘club’ exclusive of girls and that the girls can only join in if they ‘cook’ for them. This shows enforc

For example, in the Channel 4 series: The Secret Life of Five Year Olds, in which some of the boys demonstrate a historically held view by boys that they belong to a ‘club’ exclusive of girls and that the girls can only join in if they ‘cook’ for them. This shows enforc Lack of self-understanding leads to a fear of what others perceive us as and an introversion of our views and understanding of others. Encouraging children to experiment with different groups of toys and clothing regardless of gender allows the child to develop understanding and appreciation of differing views and cultures. Although it may be said that it is the job of the parents to decide what their children play with, school is the only place in which we can ensure that every child is given the appropriate tools to navigate our social world. Making this sort of experimentation a compulsory part of the curriculum ensures through policy that self-knowledge is fostered and embraced.

Lack of self-understanding leads to a fear of what others perceive us as and an introversion of our views and understanding of others. Encouraging children to experiment with different groups of toys and clothing regardless of gender allows the child to develop understanding and appreciation of differing views and cultures. Although it may be said that it is the job of the parents to decide what their children play with, school is the only place in which we can ensure that every child is given the appropriate tools to navigate our social world. Making this sort of experimentation a compulsory part of the curriculum ensures through policy that self-knowledge is fostered and embraced. The danger of society requiring men and consequently boys to prove themselves as strongly masculine is that it steers them towards restricted options. To excel intellectually or to find another physical way to succeed in expressing this ‘masculinity’. This puts restrictive pressure on boys and creates friction between and within the genders. It creates segregation between those who express their masculinity intellectually and those who express their masculinity in a more physical way. This differentiation leads to exclusion of ‘gentle’ academic boys and girls, and a lack of academic confidence and support of the boys who express this physical masculinity.

The danger of society requiring men and consequently boys to prove themselves as strongly masculine is that it steers them towards restricted options. To excel intellectually or to find another physical way to succeed in expressing this ‘masculinity’. This puts restrictive pressure on boys and creates friction between and within the genders. It creates segregation between those who express their masculinity intellectually and those who express their masculinity in a more physical way. This differentiation leads to exclusion of ‘gentle’ academic boys and girls, and a lack of academic confidence and support of the boys who express this physical masculinity.