by Camilla Beghin

Summer 2020, Covid-19 shut the world down. Why not restart dating then? Needless to say, I realised soon that Covid had changed the dating scene. That is when a friend of mine, let’s call him Harry, encouraged me to try online dating. Just before, like some character from a fairytale preparing me for a quest, he told me: “You have to step up your game!” He then informed me that as a white, European man, getting matches is a mission.

Summer 2020, Covid-19 shut the world down. Why not restart dating then? Needless to say, I realised soon that Covid had changed the dating scene. That is when a friend of mine, let’s call him Harry, encouraged me to try online dating. Just before, like some character from a fairytale preparing me for a quest, he told me: “You have to step up your game!” He then informed me that as a white, European man, getting matches is a mission.

Throughout the years, he was not the only man who mentioned to me the difficulties within the online dating world.

Two years later, I realise the complexity of online dating. There are so many hierarchies: between genders, among males and between ethnicities. So, as online dating is increasingly more relevant in the after-pandemic in the UK (Gevers, 2021), I want to present these dynamics.

The above figure shows the tendency of online dating use from the start of the pandemic in the UK. The surge in August can be associated with an easing of the restriction imposed by the government, allowing more people to socialise (Gevers, 2021).

Females at the top

Following Mead’s model of society and gender (1935), it supports a hierarchy that places men as dominant and females as dominated (applicable to most aspects of social life). Online dating seems an exception. Let’s take the case of Tinder, the most used online dating app for my age group (18-29) (Statista, 2022): the data suggests there were 9 men for every woman in 2019. This reverses the traditional power roles. Women have more choice. We stand at the top of the hierarchy deciding the rules. Turns out, Harry is right: men have to step up their game! For a couple of matches he got on Tinder that summer, I would get about 50: I had much more choice.

But do women really have power? I had to step up my game too. How? By conforming to the traditional ways of “doing gender” through gender performance (see Messner, 2000; West and Zimmerman, 1987). Both Harry and I would choose the best pictures, select the best information about us. Some people go further. They use deception to perform gender to appear attractive (see Ankee and Yazdanifard, 2015). So yes, women have more power, but within the traditional gender performance boundaries.

Fessler, 2017

Men’s double hierarchy

Harry did not realise that he was also part of a male hierarchy. Being at its top means getting more matches. This is something another friend, let’s call him Tom, told me: in Exeter he has to compete with rugby lads and various sporty men; he struggles to stand out. After talking with various girls, I realised this fits the male hierarchy suggested by Connell and Messerschmidt (2005). We have 3 main types of men, and intersections of them:

• Hegemonic males: physically active and intellectually or socially powerful.

• Complicit males: receiving benefits of patriarchy.

• Subordinated males: minorities, often part of LGBTQ+.

I can see similar patterns on Tinder. Men try to prove their level of masculinity between hegemonic and complicit (as I participated in heterosexual dating, I cannot speak for the last group). So they show off sport abilities, drinking habits, and their degrees as opposed to simply their hobbies and passions.

This revealed men have a double struggle: they have less power than women and they compete to come across as more desirable by performing the “best” masculinity.

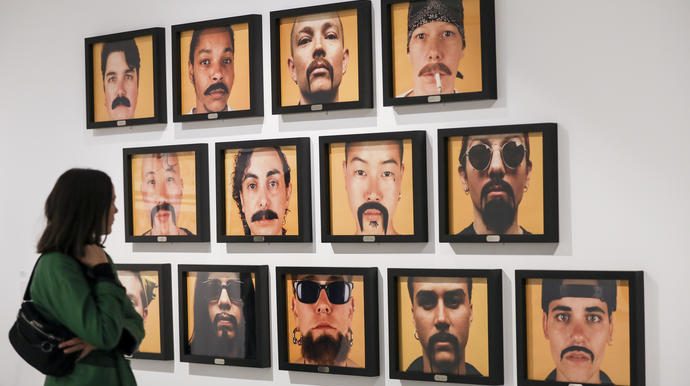

Intersectionality with ethnicity

We cannot only consider gender in online dating: ethnicity is equally important. In their study in the USA, Lin and Lundquist (2013) prove how ethnicity plays a strong part in dating selection. They were analysing the intersection between race, education and gender to understand tendencies in online dating. So, they discovered a tendency for women to respond to men of similar ethnicity or higher, whilst non-black man to ignore black women. This complicated the hierarchy adding other ladders.

I experience how my Italian origin was perceived as more “exotic”, so more attractive by British men. As a white, Italian woman I used it to step up my game, but I am conscious that some women’s ethnicity might be a factor damaging their chances.

So, ethnicity complicates the previous hierarchies. Some ethnicities (usually white) are considered advantaged compared to others. Also, within the same ethnicity, there is a tendency to reproduce gender hierarchies. Men over women.

My conclusions

• Heterosexual online dating has different hierarchies: between women and men, among men, between ethnicities.

• Both genders “perform gender”

• Ethnicity plays an important role: complicating the hierarchies.

As a white, “exotic”, woman it worked for me. Was I in a different position in the hierarchy, I would be wondering just as Tom: why the heck am I doing this to myself?

Bibliography:

Ankee, A.W. and Yazdanifard, R (2015) The Review of the Ugly Truth and Negative Aspects of Online Dating, Global Journal of Management and Business Research: E-Marketing. 15(4).

Chen, O. (2022) You are more than Tinder. online Available at: https://ozchen.com/you-are-more-than-tinder/Accessed: 15 March 2022.

Cherednichenko, S. (2020) Top 10 Dating Apps in 2020, mobindustry. online Available at: https://medium.com/mobindustry/top-10-dating-apps-in-2020-1f35b0c624b6 Accessed: 15 March 2022.

Connell, R.W. and Messerschmidt, J.W. (2005) Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept, Gender & Society. 19(6): 829-859.

Fessler, L. (2017) Tinder now shows its premium customers who likes them – even when the feeling’s not mutual., Quartz. online Available at: https://qz.com/1064995/tinder-gold-premium-membership-likes-me-function-can-i-see-who-already-swiped-right-on-me-on-tinder/ Accessed: 15 March 2022

Gevers, A. (2021) Online Dating in Europe, ComScore. online Available at: https://www.comscore.com/Insights/Blog/Online-Dating-in-Europe Accessed: 4 March 2022.

Lin, K. and Lundquist, J. (2013) Mate Selection in Cyberspace: The Intersection of Race, Gender, and Education, American Journal of Sociology. 119(1): 183.215.

Mead, M. (1935) Sex and temperament in three primitive societies. New York: William Morrow.

Messner, M.A. (2000) Barbie Girls Versus Sea Monsters: Children Constructing Gender, Gender & Society. 14(6): 765-784.

Statista (2022) Share of individuals who were current or past users of online dating sites and apps in the United Kingdom (UK) in June 2017, by age group, Statista. online Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/714211/online-dating-site-and-app-usage-in-the-united-kingdom-by-age-group/ Accessed: 5 March 2022.

West, C. and Zimmerman, D.H. (1987) Doing Gender, Gender & Society. 1(2): 125-151.