Markus Eberhardt (University of Nottingham) and Francis Teal (Centre for the Study of African Economies, University of Oxford)

“We compare this [input] index with our output index and call any discrepancy ‘productivity’… It is a measure of our ignorance, of the unknown, and of the magnitude of the task that is still ahead of us.” Zvi Griliches (1961)

It is an unfortunate misconception that the canonical Solow-Swan growth model necessarily implies that all economies in the world, rich or poor, industrialised or agrarian, possess the same production technology.[1] As the above quote shows there are prominent critics of this assumption while Solow himself suggested that “whether simple parameterizations do justice to real differences in the way the economic mechanism functions in one place or another” was certainly worth ‘grumbling’ about.[2] Nevertheless, the notion that cross-country empirical analysis should, in case of accounting exercises, adopt or, in case of regression analysis, aim to arrive at a common capital coefficient of around 0.3 for all countries is deeply ingrained in the minds of growth economists.

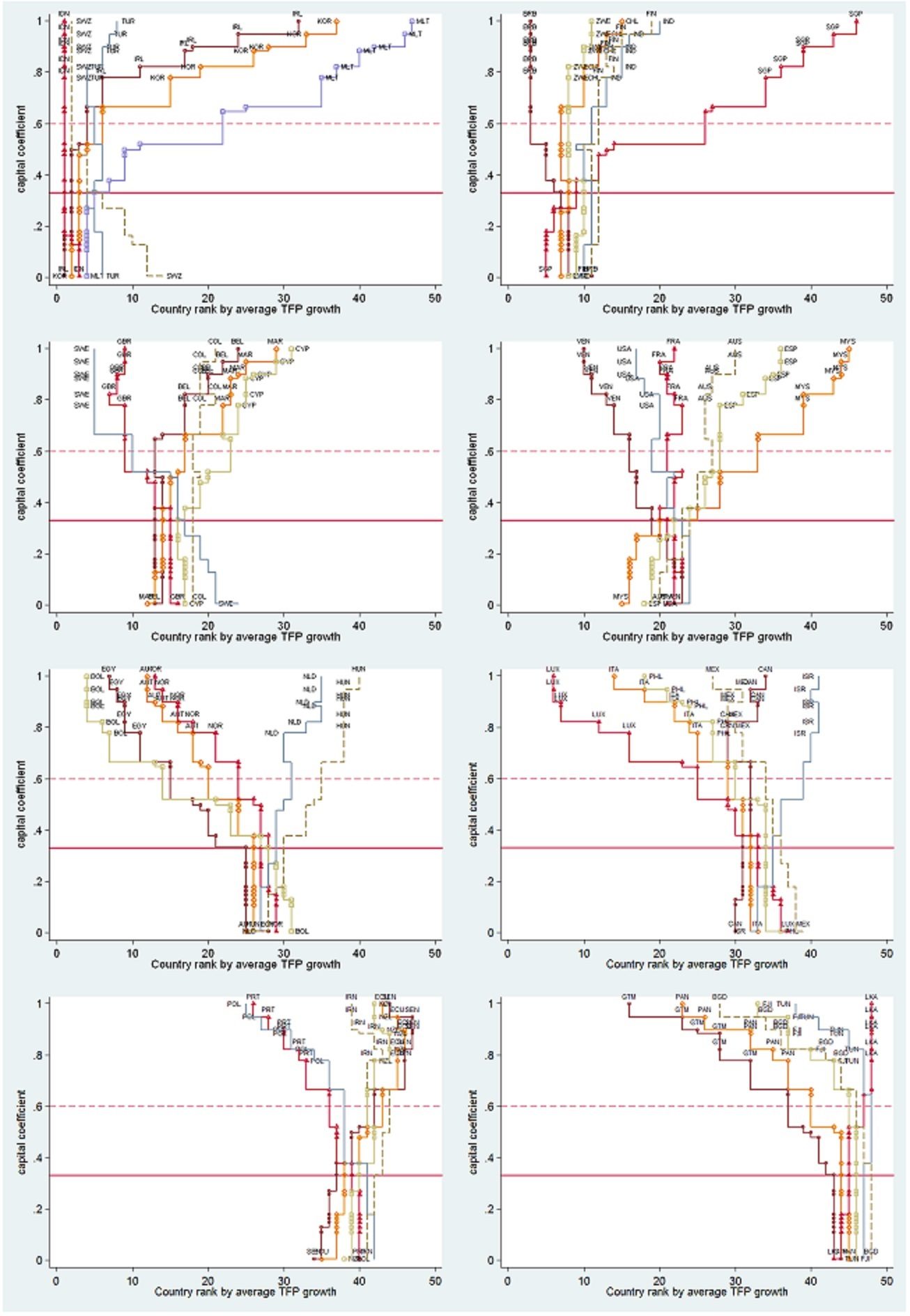

In a forthcoming paper, we take an alternative approach to revisit the issue of whether technology is common across countries.[3] But before we discuss the approach and findings of that paper, we want to briefly illustrate why the assumption of a common capital coefficient is questionable. If the commonly adopted value for the capital coefficient of 1/3 were of great significance then we would expect total factor productivity (TFP) estimates from standard growth accounting exercises to differ substantially once we chose different values for the capital coefficient, in particular for values close to zero. Our data exercises proceed as follows: we first draw a random capital coefficient between zero and one, which we employ to compute annual TFP growth via standard growth accounting. The accounted country-specific TFP growth is then averaged over time and countries are ranked by TFP growth magnitude. This process is then repeated 1,000 times.

An important feature of this analysis and also our study is the focus on manufacturing. The central importance of this industrial sector for successful development is (still) a widely recognised ‘stylised fact’ in development economics. Yet in contrast to the literature on cross-country growth regressions using aggregate economy or agriculture data there is comparatively little empirical work dedicated to the analysis of the manufacturing sector in a large cross-section of countries. If manufacturing matters for development it seems self-evidently important to learn about the production process and its drivers in this industrial sector.

A visual illustration of the results from the 1,000 growth accounting exercises is provided in Figure 1: the ‘Baobab trees of growth accounting’. We split the 48 countries in the sample into 8 groups, based on the rankings implied by their average TFP growth rate when the capital coefficient is 1/3. On the y-axis of each plot we indicate the capital coefficient applied in the growth accounting exercise, while the x-axis indicates the resulting rank of each country from 1 to 48 in terms of average TFP growth. All of the plots show the same pattern, resembling a Baobab tree, with a narrow ‘trunk’ and a spreading out of the upper ‘crown’. We conclude that provided the capital coefficient is assumed common across countries it is entirely unimportant what value is chosen for this parameter, since the productivity rankings based on TFP growth rates are essentially unchanged for ‘reasonable’ values of the capital coefficient. We only see considerable change if the capital coefficient is greater than 0.6, which we know is an unreasonable parameter value. This finding raises serious doubts over the validity of the common technology assumption maintained in these computations.

Figure 1

In our paper, we compare and contrast regression results from different estimators which make different assumptions about production technology and TFP: whether technology differs or is common across countries, whether TFP levels and growth rates differ or are common across countries. While the theoretical literatures on growth and econometrics provide solid foundations for technology heterogeneity as well as the time-series and cross-section properties of macro panel data we highlight in our paper, these have in practice not been considered in great detail in the empirical growth literature. Since most growth economists are not familiar with our preferred set of empirical estimators, we motivate and discuss them in the paper at great length. These methods enable us to model country-specific production technology and time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity across countries (differential TFP levels), but also time-variant unobserved heterogeneity to capture differential TFP evolution over time in a very flexible manner.

Our analysis establishes that assuming a common technology parameter for all countries yields very serious bias in the capital coefficient, with parameter values ranging from 0.6 to 0.8, far in excess of the macro evidence of 0.3. The heterogeneous parameter estimators yield uniformly lower capital coefficients, much more in line with the aggregate economy factor income share data. Based on formal diagnostic testing, our empirical results favour models with heterogeneous technology which account for a combination of heterogeneous and common TFP and reject the notion of common technology. We also carried out a significant number of formal parameter heterogeneity tests which confirmed this result.

Our general production function framework provides a number of alternative insights into macro TFP estimation. Firstly, it seems prudent to allow for maximum flexibility in the structure of the empirical TFP terms: if TFP represents a ‘measure of our ignorance’ then it makes sense to allow for differential TFP across countries and time. Secondly, it further makes sense to keep an open mind about the commonality of TFP: while early empirical models assumed common TFP growth for all countries, later studies preferred to specify differential TFP evolution across countries. We believe the arguments for commonality (non-rival nature of knowledge, spillovers, global shocks) and idiosyncracy (patents, tacit knowledge, learning-by-doing) call for an empirical specification which does not rule out either by construction. Thirdly, an empirical specification that allows for parameter heterogeneity across countries and for a shift away from the widespread focus on TFP analysis and toward an integrated treatment of the production function in its entirety appears to fit the data best. The Baobab Tree accounting exercises illustrate the very limited insights to be gained from the assumption of a common technology framework.

Our analysis represents a step toward making cross-country empirics relevant to individual countries by moving away from empirical results that characterise the average country and toward a deeper understanding of the differences across countries. Further, the key to understanding cross-country differences in income is not exclusively linked to understanding TFP differences, but requires careful consideration of differences in production technology. Since modelling production technology as heterogeneous across countries requires an entirely different set of empirical methods we have focused on developing this aspect in the present paper and have left empirical testing of rival hypotheses about the patterns and sources of technological differences for future research.

References

Eberhardt, Markus, and Francis Teal (2019); “The Magnitude of the Task Ahead: Macro Implications of Heterogeneous Technology.” Forthcoming in the Review of Income and Wealth.

Griliches, Zvi, (1961); “Comment on An Appraisal of Long-Term Capital Estimates: Some Reference Notes by Daniel Creamer.” Output, Input, and Productivity Measurement (NBER), pp. 446–9.

Solow, Robert M., (1986); “Unemployment: Getting the Questions Right.” Economica, 53(210): S23–34.

Endnotes

[1] We refer to ‘technology heterogeneity’ to indicate differential production function parameters on observable inputs across countries, with unobservables captured as TFP.

[2] See Solow (1986 S23)

[3] See Eberhardt and Teal (2019)