We would like to thank The Department of Economics and the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University, for hosting and sponsoring the 5th InsTED Workshop. We are also grateful for sponsorship and organizational support from the Moynihan Institute of Global Affairs, as well as sponsorship from the Program for the Advancement of Research on Conflict and Collaboration (PARCC) and the University of Exeter Business School. The workshop took place at the Maxwell School from May 15th-16th 2018. Special thanks go to Kristy Buzard and Devashish Mitra as joint chairs of the local organizing committee, and Juanita Horan for her extremely helpful interactions with everyone.

The program comprised of 18 papers ranging over four broad topics at the intersection of institutions, trade and economic development. The first was global value chains, focusing on how they are determined at the firm level, and what their implications are for economic outcomes, especially in the developing world. The second topic examined ongoing concerns about the implications of trade integration for income distribution, with emphasis on a developing country perspective. The third concerned the interaction between trade integration or other institutional reform and resource allocation. The fourth was on institutional constraints on international trade policy, including a look at the implications of restrictions imposed by the World Trade Organization. There now follows a summary of all the papers presented at the workshop, organized under these four topic headings. A bibliography, together with links to papers where available, is provided at the end. Please note that for brevity the summary mentions presenters’ names but not those of their co-authors. This information is contained in the bibliography.

Global Value Chains: Their Determinants and Implications

The spread of global value chains (GVCs) over the last thirty years or so has been a key new feature of the current wave of globalization, and important for the integration of developing countries into the world economy. At the broadest level, the spread of GVCs has been facilitated by innovations in information and communication technology, the deepening of trade liberalization and ongoing reduction in transport costs, and political developments principally involving the fall of the iron curtain. But in this globally more integrated environment, there is growing appreciation that firm-level decisions play a critical role in the determination of how global value chains actually form. The outcome of these decisions has been characterized in terms of GVCs forming either as ‘spiders’, where a central ‘body’ imports inputs for assembly from various ‘legs’ that originate in different countries, or where a product is assembled sequentially along the length of a ‘snake’. Such trade in intermediate inputs now accounts for 70% of global trade, spanning not just developed but developing countries as well.

The keynote address by Pol Antràs discussed his research project to model how firm-level extensive margin sourcing decisions are made, that give rise to the formation of GVCs. His motivation of the need for a new model was that the canonical Melitz model renders firm export decisions tractable by assuming constant (exogenous) marginal costs, while firm import decisions are made specifically to lower marginal costs which are therefore endogenous. The interdependence in a firm’s extensive margin import decisions complicates the firm’s problem considerably. In the case of a spider, this involves a combinatorial problem with 2J possible choices, where J denotes the number of possible source countries. In the case of a snake, the problem is similarly complex.

Antràs presented two papers, which provide tractable ways to model firm decisions in the cases of spiders and snakes respectively in ways that can be estimated structurally in the data. In the case of spiders, the modelling approach is to apply an iterative algorithm that exploits complementarities in the decision of a firm to import from particular markets, and uses lattice theory to reduce the dimensionality of the firm’s optimal sourcing strategy problem. The results show that while the ‘China shock’ resulted in an overall decline in domestic sourcing by US firms, the most productive firms actually increased domestic sourcing due to the cost savings derived through sourcing from China. In the case of snakes, where the value chain is sequential, Antràs showed that the lead firm’s problem becomes one of solving the least cost path through a sequence of suppliers. By applying a different algorithm the paper shows that, other things equal, it is optimal to locate relatively downstream stages of production in relatively central locations. He then discussed counterfactual exercises that illustrate how changes in trade barriers affect the extent to which various countries participate in domestic, regional or global value chains, and traces the real income consequences of these changes. Using this approach, substantial income gains are shown to arise from the increased participation of low-income countries in GVCs.

A key question motivating the literature on the extensive margins of trade is whether better firm performance gives rise to exporting or, conversely, exporting improves firm performance. A particular form of this question is as follows: if offered the opportunity to export through a marketing arrangement in a developed country, can firms in developing countries upgrade the quality of the goods they produce and export, thereby increasing their incomes? Rocco Macchiavello presented a paper on the case of the Nespresso sustainable quality program in Colombia. The dataset constructed for the paper matches detailed administrative data on the universe of Colombian Coffee farmers with transaction-level data along three stages in the coffee chain, from the export gate to the farm gate. Machiavello and his collaborators find that the program induced farmers to upgrade their coffee plantations, expand their farms as well as production, increase the quality of the coffee produced, and the loyalty of their marketing arrangement. Most notably, a price premium of approximately 5-8% is fully transmitted along the supply chain, from the export gate to the farm gate, thereby bringing significant income gains to farmers in the developing world. This paper therefore adds to the evidence supporting the view that gaining the opportunity to export can indeed enhance firm performance.

While GVCs can potentially increase incomes by creating cost advantages and quality improvements, there is widespread concern that cost advantages may be gained through lax environmental and labor regulation in countries where suppliers are located. Sebastian Krautheim presented a paper studying this issue both theoretically and empirically. In the model of his paper, a Northern firm can save costs by outsourcing to a Southern supplier that uses a cost-saving but unethical technology. Contracts are incomplete, so that a firm has limited control over unethical technology choices of suppliers along the value chain. The technology is a credence characteristic, in that consumers care about it but cannot know what it is. However, the model features a non-governmental organization (NGO) that can reveal the technology being used. Using the unethical technology creates an incentive to increase scale, but this also increases the probability of being detected by the NGO. The paper provides empirical support for the model’s prediction that a high cost advantage of ‘unethical’ production in an industry and a low regulatory stringency in the supplier’s country favor international outsourcing as opposed to vertical FDI.

Trade Integration and Income Distribution

There has long been a concern that deeper trade integration causes an increase in inequality. This is the focus of the famous Stolper-Samuelson Theorem, which arises directly from the classic Hecksher-Ohlin model and in a wider set of settings as well. It predicts that if, compared to the South, skilled labor is relatively abundant in the North while unskilled labor is relatively scarce, then deeper trade integration will drive an increase in inequality in the North and a decrease in the South. Previous academic debates tended to focus on the rise in inequality in the North, and the extent to which trade integration with the South was ‘to blame’.

In her keynote address, Nina Pavcnik presented her literature review that assesses the current state of evidence on how international trade shapes inequality and poverty. Her review focuses mainly on developing countries, reflecting the fact that there is now more evidence in that context, but her discussion drew parallels to the empirical evidence on developed countries as well. Her review also discusses perceptions about international trade in over 40 countries at different levels of development, including perceptions on trade’s overall benefits for the economy, trade’s effect on the livelihood of workers through wages and jobs, and trade’s contribution to inequality. In framing the review, she noted that while most studies of developed countries focus on import shocks, studies of developing countries present evidence on export shocks as well to provide a more nuanced picture.

One insight that emerges from Pavcnik’s review is that losers from trade liberalization tend to be geographically concentrated and persistent over time because the costs are large. Another insight is that worker-firm affiliation matters for how individuals are affected by trade liberalization. Better performing firms tend to be better equipped to respond to the opportunities arising from trade liberalization. Declines in industry employment from import competition are concentrated in less productive firms and workers. A third insight is that one cannot ignore the effects of the informal sector in developing countries. In some cases, international trade supports economic development by promoting the transfer of labor from inefficient informal firms to more efficient formal firms. In others, especially where labor markets are poorly functioning or government support for those displaced from employment by trade is absent, the informal sector can serve as a coping mechanism for trade shocks. Pavcnik noted that these outcomes are in some cases at significant variance to the predictions derived from the classic H-O model, especially because it does not have a role for firms. The main policy recommendation to come out of her review was that governments must support workers and not jobs, because it is inevitable that the gains from trade are realized through the destruction of jobs, and the costs to workers are substantial.

The program featured two papers that studied the effects of trade policy in India. The paper presented by Beyza Ural Marchand studies the distributional implications, with a particular focus on the poor, by asking: ‘what would be the distributional effects of eliminating the current protectionist structure?’ Thus her focus is on the welfare implications of a move from current trade policies to free trade. The welfare effects are estimated through household expenditure and earnings effects of liberalization. The results indicate that Indian trade policy is pro-poor through the earnings channel, as its elimination leads to higher welfare losses for poorer households. But it is pro-rich through the expenditure channel, as its elimination leads to higher welfare gains for poorer households. On balance, surprisingly, Marchand finds that Indian trade policy is regressive overall.

The paper presented by Ariel Weinberger investigates the liberalization episode in India during the 1990’s, which has been characterized by large and unexpected changes in trade and foreign investment policies. Contrary to what might have been expected, given the secular decline in labor shares since the 1980s, his paper finds that trade reforms mostly raised the labor-to-capital relative factor shares in India. A reduction in capital tariffs and liberalization of FDI raise the share of income paid to labor relative to capital. His results reveal access to foreign capital as a new mechanism through which openness affects factor shares: imported capital augments technical change and potentially reduces rental rates, both of which raise the relative labor share. Weinberger and his collaborator attribute the observed overall decline in the labor share to domestic deregulation policies and credit expansion.

Richard Chisik reversed the direction of enquiry relative to the papers above. Rather than look at the effects of trade on inequality, his paper considers the effect of inequality on trade. The prior literature notes that a foreign transfer may generate a ‘Dutch disease’ type effect in the recipient country: a transfer brings about a real exchange rate appreciation via an increase in wages that can reduce the size of the manufacturing sector. This may reduce manufacturing exports or even eliminate a comparative advantage in manufacturing altogether. In this literature, remittances have been considered isomorphic to foreign aid in causing the Dutch disease. Chisik’s paper questions this apparent similarity. His paper argues that, whereas aid generates a Dutch disease effect, remittances can lead to growth of manufacturing. The reason is that (ironically) aid tends to go to wealthier individuals who spend the money on non-traded services, which does appreciate the real exchange rate and shrinks the manufacturing sector, while remittances tend to go to poorer individuals who spend on manufactures which tends to increase the size of that sector. The differing effects on the relative size of the manufacturing sector have, in turn, different bearings on comparative advantage. The paper presents econometric results supportive of their model.

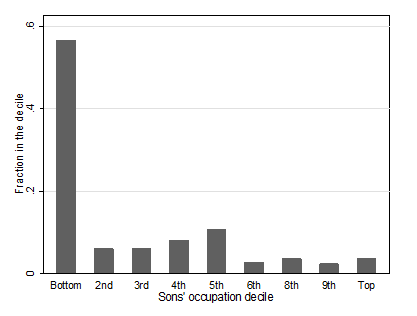

Rather than focus directly on trade and inequality, Ben Zissimos looked at how the inequality created by international trade can threaten the survival of dictatorships, especially in the face of world price shocks. In his paper, the survival of dictatorships is taken to be a bad thing because they tend to support extractive economic institutions that fail to promote economic development. The theory developed in the paper predicts that, in food exporting dictatorships, a world food price spike can provoke the threat of revolution. Dictatorships are predicted to respond by making transfers using export taxes, hence defusing the threat of revolution and forestalling democratization. The prior literature on institutions and development has tended to focus on the use of domestic redistributive taxation for the purposes of defusing the threat of revolution. But the paper presented by Zissimos draws on evidence to suggest that dictatorships do not install domestic redistributive capacity for fear that it will be used to tax away their wealth. Trade taxes, which are available to dictators, are used instead for this purpose. Hence the paper proposes a new motive for the use of trade policy. It also provides econometric results supportive of the predictions of the model.

Trade and Resource Reallocation Effects of Trade Integration and Institutional Reform

As tariffs have been reduced through multilateral trade rounds and the formation of free trade agreements, attention has shifted to other measures such as product standards, intellectual property protection, and infrastructure in an effort to facilitate integration where appropriate.

The paper presented by Walter Steingress quantifies the heterogeneous trade effects of harmonizing standards on product entry and exit as well as export sales. Using a novel and comprehensive database on cross-country standard equivalences, the paper identifies standard harmonization events. To track harmonization events, the paper presents a new correspondence table between the International Classification for Standards (ICS) and Harmonized System (HS) codes. The results Steingress reported show that, on average, standard harmonization leads to a 0.5% increase in export sales. This effect is driven by an increase in the intensive margin, a decrease in prices and an increase in the quantities sold. The paper argues that these results are compatible with a theoretical framework where standard harmonization leads to higher fixed costs as companies have to adapt to the new standards, but simultaneously reduced variable costs, thus increasing overall trade flows.

In her paper, Magdalene Silberberger broaches the impact of trade liberalization on health, safety and environmental (HSE) standards. She and her collaborator ask whether tariff liberalization causes ‘regulatory chill’, meaning that countries are reluctant to implement HSE standards, or instead causes a race to the top as governments seek to use standards as non-tariff barriers to trade. Her paper analyzes annual country-by-industry data on notifications of changes in sanitary and phytosanitary standards by WTO members. The results suggest that the impact of increased trade pressure depends on whether domestic producers are likely to gain or lose from a change in standards. Regulatory chill is the dominant response in most countries, but countries in which producers can adapt to standards relatively cheaply appear to race to the top. Consequently, that paper concludes that tariff liberalization is associated with a divergence in standards across countries.

Shifting the focus from standards to patents, Tom Zylkin explored the effects of cross-border patents on international trade. His paper highlights an ambiguity as to what one might expect here. On the one hand, a firm might file a patent in another country because it wants to protect a good that it plans to export there. On the other hand, the reason for filing a patent in another country might be that the firm wants to produce a good there instead of exporting it. So, he argued, cross-border patents could be complements or substitutes to trade. Using a highly disaggregated database of all patents filed in and out of developed and developing countries, his paper provides the first systematic analysis of how bilateral trade responds to bilateral filings. It reports results suggesting large roles for geographic as well as industry-level heterogeneity, suggestive of competing motivations for cross-border patenting. Patents promote bilateral exports—and negate bilateral imports—in high-demand elasticity industries, but can have the opposite effect in industries where the products are primarily used as intermediate inputs and/or between countries that are not far apart geographically.

The final two papers in this section consider the effects on economic performance of fundamental changes to the domestic economic and political environment. Mingzhi (Jimmy) Xu‘s paper studies the aggregate and distributional impacts of China’s high-speed railway (HSR) network. China’s HSR is a passenger rail network that covers 29 of the country’s 33 provincial-level administrative divisions and exceeds 25,000 km/16,000 miles in total length, accounting for about two-thirds of the world’s high-speed rail tracks in commercial service. Xu argued that HSR connection generates productivity gains by improving firm-to-firm matching efficiency and leading firms to search more efficiently for suppliers. His paper first provides reduced-form evidence that access to HSR in China significantly promotes exports at the prefecture level. It then constructs and calibrates a quantitative spatial equilibrium model to perform counterfactuals, taking into account trade, migration, and outsourcing. The quantitative exercise reveals that the construction of HSR between 2007 and 2015 increased China’s overall welfare by 0.46%, but was also associated with an increase in national inequality. In addition, the paper finds that gains from HSR are larger when labor migration costs are higher, implying that the HSR project is well suited to a country like China, which features high internal migration barriers.

Ama Baafra Abeberese’s paper considers the implications of democratic reform for firm productivity, and in particular the impact of President Suharto’s unexpected resignation from the Presidency of Indonesia in 1998, after more than three decades in the post. The basic idea underpinning the paper is that politicians can create high entry barriers for firms in order to collect rents from those that do enter. Arguably, since this concentrates the gains from economic activity, democratically elected politicians will be less able to create such barriers without being displaced from office, and so the environment under democracy should be more competitive. However, the effect on firm productivity is ambiguous since a more competitive environment may make it more difficult for firms to become established. Baafra’s paper uses the fact that, in Indonesia, local mayors’ terms were asynchronous. This asynchronicity of terms means that the paper can identify variation in the productivity of firms operating under mayors appointed by Pres. Suharto versus mayors who were democratically elected after Suharto stepped down. The main result Baafra presented was that democratization did in fact boost productivity, and more so in industries that were shown to be politically connected to the Suharto regime and hence presumably more sheltered when he was in office.

Institutional Constraints on Trade Policy

While it might be collectively rational for countries to adopt free trade, it is often individually rational for a government to adopt some degree of trade protection. This observation has been used to provide motivation for why governments sign up to institutional measures that constrain their abilities to set trade policy unilaterally, often in the form of a trade agreement. This way of thinking forms the basis for the literatures on the purpose of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), now absorbed into the Articles of the World Trade Organization (WTO), as well as the purpose of preferential trade agreements.

David DeRemer opened the discussion of these issues at the workshop with a paper that provides a new framework for thinking about international trade agreements in modern trade environments such as those involving offshoring, and rent seeking by foreign governments. These are environments that extend beyond those which standard models of trade agreements are set up to consider. His presentation started out by taking a stance on what distinguishes modern trade negotiation environments from the earlier era. The new framework he developed focuses on how trade agreements help countries to escape from prisoner’s dilemmas in which each government disregards the effects of local price, as opposed to world price, changes on trading partners. He argued that, typically, these local prices matter because they affect foreigners’ producer surplus or value-added.

His paper considers trade agreements that achieve the stable end-point of reciprocal negotiations, meaning a situation where neither government can gain from policy changes that affect net export value equally. The paper shows this end point is Pareto efficient for governments, so it is a suitable prediction for the trade negotiation outcome. This stable and efficient outcome for modern trade environments yields new predictions that are consistent with empirical evidence. For example, more politically organized exporters with large supply elasticities compel governments to undertake greater reductions in cooperative import tariffs from trade negotiations. In this setting, governments jointly pursue gains for exporters to the extent that they would assess losses for domestic firms from import competition to be outweighing gains for consumers.

Woan Foong Wong’s paper focused specifically on the main WTO rules that govern free trade agreement (FTA) formation. Her paper is based on a three country ‘competing exporters model’, where any two countries compete to export a given product to the third country. An FTA can then be formed between two countries, leaving the third one out, or all three countries can adopt global free trade, with the outcome being endogenously determined. FTA formation under Article 24 of the GATT/WTO requires that external tariffs not be raised, and all internal tariffs be removed. Wong’s paper examines the implications of the requirement to remove internal tariffs by comparing the outcome when this requirement is adhered to with when it is relaxed. She showed that requiring FTAs to eliminate internal tariffs makes the non-member better off although it simultaneously reduces the likelihood of achieving global free trade by encouraging free-riding on its part. The reason is that setting lower internal tariffs creates an incentive for members to set lower external tariffs, since they compete more aggressively for the third market, which benefits the non-member. This problem is avoided by customs union members who, unlike FTA members, coordinate their external tariff. Therefore, surprisingly, in the case of FTA formation removing the ‘free internal trade requirement’ increases the parameter space where global free trade is a stable outcome.

Other papers at the workshop undertook econometric work to explore the implications of trade agreement formation. The paper presented by Kishore Gawande undertook the first econometric test of the commitment-based theory of trade agreements. The idea of this theory is that import-competing sectors where industry interest groups know they can lobby the government for protection will end up with tariffs set above efficient levels and over-investment in capital. But if governments realize that they cannot receive sufficient compensation for such long-run distortions, they may choose to sign a trade agreement and thus tie their hands to efficient trade policy, thereby shutting down lobbying altogether. Gawande’s presentation reported econometric results testing this theory against industry-level and firm-level data, and found supportive evidence for the model in the data.

Yifan Zhang‘s paper investigates the impacts of trade liberalization on household behavior and other outcomes in urban China resulting from that country’s entry to the WTO in 2001. The identification strategy employed in the paper exploits regional variation in the exposure to the resulting tariff cuts. The paper finds that workers in regions initially specialized in industries facing larger tariff cuts experienced relative declines in wages. Households responded to these income shocks in several ways. First, household members were found to work more, especially if they moved into the non-tradable sector. Second, young adults were more likely to live longer in the parental household, and so average household size increased. Third, households tended to save less. These changes in bahavior were interpreted as being motivated by attempts by households to buffer themselves against the negative wage shocks induced by trade liberalization.

There is a long-held view in the trade policy literature that traditional tariff instruments and temporary protection (TP) measures such as anti-dumping and countervailing duties are substitutes. However, David J. Kuenzel argued in his presentation that there is only mixed empirical evidence for a link between tariff reductions and the usage pattern of antidumping, safeguard and countervailing duties. Based on recent theoretical advances, his paper argues that the relevant trade policy margin for implementing TP measures is instead the difference between WTO bound and applied tariffs, or ‘tariff overhang’ as it is often known. Lower tariff overhangs constrain countries’ abilities to raise their MFN applied rates without legal repercussions, independent of past tariff changes. Using detailed sectoral data for a sample of 30 WTO member countries during the period 1996-2014, Kuenzel finds strong evidence for an inverse link between tariff overhangs and TP activity. This result implies that tariff overhangs and TP measures are substitutes. Based on this finding, he argues that this indicates the importance of existing tariff commitments as a key determinant of alternative TP instruments.

Bibliography of Papers Presented with Links Where Available (Presenters’ Names Shown in Bold)

Abeberese, A.B., P. Barnwal, R. Chaurey, and P. Mukherjee “Firms Under Dictatorship and Democracy: Evidence from Indonesia’s Democratic Transition.”

Aisbett, E., and M. Silberberger “Tariff Liberalisation and Protective Product Standards.”

Antràs, P., T.C. Fort and F. Tintelnot, “The Margins of Global Courcing: Theory and Evidence from US Firms.”

Antràs, P., and A. de Gortari, “On the Geography of Global Value Chains.”

Abeberese, A.B., P. Barnwal, R. Chaurey, and P. Mukherjee, “Firms under Dictatorship and Democracy: Evidence from Indonesia’s Democratic Transition.”

Baccini, L., H. Cheng, K. Gawande, and H. Jo, “The Political Economy of Trade Agreements: A Test of a Theory.”

Behzadan, N., and R. Chisik “The Paradox of Transfers: Distribution and the Dutch

Disease.”

Brunel, C., and T. Zylkin “Do Cross-Border Patents Promote Trade?”

Dai, M., W. Huang, and Y. Zhang, “How Do Households Adjust to Trade Liberalization? Evidence from China’s WTO Accession.”

DeRemer, D.R., “The Principle of Reciprocity in the 21st Century: New Predictions for Trade Agreement Outcomes.”

Gawande, K., and B. Zissimos, “How Dictators Forestall Democratization Using International Trade Policy.”

Herkenhoff, P., and S. Krautheim, “The International Organization of Production in the Regulatory Void.”

Kuenzel, D.J., “WTO Tariff Commitments and Temporary Protection: Complements or Substitutes?”

Leblebicioglu, A., and A. Weinberger, “Openness and Factor Shares: Is Globalization Always Bad for Labor?”

Machiavello, R., and M. Florensa, “Improving Export Quality and What Else? Nespresso in Colombia.”

Marchand, B.U., “Inequality and Trade Policy: Pro-Poor Bias of India’s Contemporary Trade Restrictions.”

Pavcnik, N., “The Impact of Trade on Inequality in Developing Countries.”

Saggi, K., W.F. Wong, and H.M. Yildiz, “Preferential Trade Agreements and Rules of the Multilateral Trading System.”

Schmidt, J., and W. Steingress, “No Double Standards: Quantifying the Impact of the Standard Harmonization on Trade.”

Xu, M., “Riding on the New Silk Road: Quantifying the Welfare Gain from High-Speed Railways.”