Aditya Dasgupta (University of California, Merced), Kishore Gawande (University of Texas, Austin), and Devesh Kapur (Johns Hopkins University – SAIS)

More than half of all nations have experienced a violent civil conflict since 1960.[1] One of the best predictors of conflict outbreak in a country is a low level of economic development and whether it has experienced a civil conflict in the past, suggesting the existence of “conflict trap” in which poverty and violence reinforce one another over time. This begs the question: how do nations break out of the vicious cycle of poverty and violence?

Poverty encourages participation in armed civil conflict in at least two ways. First, it creates economic and political grievances among impoverished groups, providing fertile ground for rebel groups to draw support from those who feel neglected by the state. Second, a lack of employment opportunities and stable livelihoods reduces the opportunity costs of participating in violent conflict, making it easier for rebel groups to recruit fighters.

If poverty fuels violence, then anti-poverty programs ought to play an important role in pacifying violent civil conflict. A large and growing scholarly literature has examined this policy implication, coming to surprisingly mixed conclusions. One randomized study of Afghanistan’s largest development program finds that the program contributed to a modest reduction in violence.[2] Another important randomized study in Liberia found that a combination of cash payments and therapy produced a durable reduction of participation in crime and violence among at-risk young men.[3] Other studies, especially those that examine the roll-out of large-scale government programs and not pilot experiments, have found that foreign aid and development programs are sometimes associated with increases in violence.[4]

How do we reconcile the conflicting evidence, especially the disjuncture between micro-level randomized studies by researchers and the program evaluation literature? We argue that state capacity, or the bureaucratic capacity of a government to successfully implement programs, may play an important role in actuating the pacifying effects of anti-poverty programs. In conditions of low state capacity, program funds are unlikely to pass through to local populations and corruption may even reinforce local grievances with the state and provide opportunities for rebel financing. When local state capacity is strong, however, antipoverty programs have a better chance of actually reducing poverty, improving perceptions of the state, and dis-incentivizing participation in deadly conflict.

To examine this hypothesis, we empirically examine how the roll-out of India’s National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (NREGS), a large-scale anti-poverty program which guarantees every rural household in India up to 100 days of public works employment, affected the intensity of the Maoist conflict, a protracted conflict between a Maoist insurgency concentrated in eastern India and the Indian government. Because the roll-out of NREGS was staggered in three phases between 2006 and 2008, we can employ a difference in differences research design. If NREGS reduced violence, we should observe a reduction in violence in districts adopting the program relative to districts experiencing no change in their program adoption status. Moreover, if these pacifying effects depended on state capacity, we should observe that these effects are mainly concentrated in districts with a high level of state capacity, which varies quite substantially across regions and districts of India.

To measure the intensity of the Maoist conflict, we assemble a new panel dataset of violent incidents and deaths at the district level, drawing on the archives of local language newspapers, which ensures that we get adequate temporal and spatial coverage of a long-simmering conflict that occurs mainly in rural areas; existing datasets that draw exclusively on English language sources are heavily biased toward more recent conflict events and those that are close to urban areas. To measure district-level state capacity, we average the ranking of districts across four indicators of basic service provision according to the 2001 census based on the share of villages with: (1) a paved road; (2) a primary school; (3) a primary health center; and (4) an agricultural credit cooperative (the lowest tier of the Indian government’s agricultural credit network).

Using these data, we come to two main findings. First, overall the adoption of NREGS was associated with a large reduction violent incidents and deaths, especially over the long run. To provide a back-of-the-envelope calculation of the size of the pacifying effects, consider the total levels of violence observed in 2008: 619 violent incidents resulting in 751 deaths. According to our regression estimates, counter-factually without the adoption of NREGS across districts, levels of total violence would have been 1,440 violent incidents resulting in 2,030 deaths suggesting that the program eliminated roughly 821 potential violent incidents and 1,279 casualties across districts in that year.

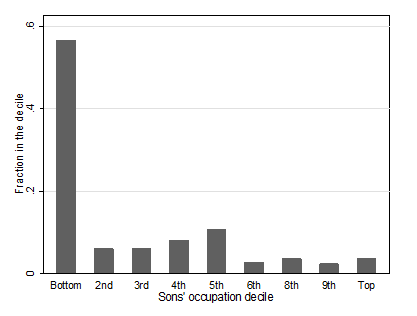

Second, these effects were concentrated in districts with high levels of state capacity. Our analysis of heterogeneous effects suggests that the violence-reducing effects of NREGS were concentrated almost entirely in the top two quartiles of districts in terms of state capacity. In the districts in the bottom two quartiles of state capacity, the program had essentially no impact on violence at all.

What conclusions do we draw? First, NREGS has probably played an important role in the long-term pacification of the Maoist conflict in India. Second, one reason for the mixed evidence from the program evaluation literature on the impact of development programs on violence is that the pacifying effects of anti-poverty programs depend heavily on state capacity, which can vary considerably across and within countries. Indeed, other recent studies have come to similar conclusions – that development programs can reduce violence, but primarily in areas where the state possesses a monopoly of violence and has the capacity to carry out its developmental activities without rebel subversion.[5]

To reduce violence, therefore, policymakers need to encourage not only development through anti-poverty programs, but also the strengthening of bureaucratic and state capacity.

References

Beath, A., F. Christia, and R. Enikolopov, (2013); “Winning Hearts and Minds Through Development: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Afghanistan.” Paper presented at the 110th Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, August, Chicago.

Blattman, C., J.C. Jamison, and M. Sheridan, (2017); “Reducing Crime and Violence: Experimental Evidence from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Liberia.” American Economic Review 107(4): 1165-1206.

Blattman, C., and E. Miguel, (2010); “Civil war.” Journal of Economic Literature 48(1): 3-57.

Crost, B., J. Felter, and P. Johnston, (2014); “Aid Under Fire: Development Projects and Civil Conflict.” American Economic Review 104(6): 1833-56.

Sexton, R., (2016); “Aid as a Tool Against Insurgency: Evidence from Contested and Controlled Territory in Afghanistan.” American Political Science Review 110(4): 731-749.

Endnotes

[1] Blattman and Miguel (2010).

[2] Beath, Christia, and Enikolopov (2013).

[3] Blattman, Jamison, and Sheridan (2017).

[4] Crost, Felter, and Johnston (2014).

[5] Sexton (2016).