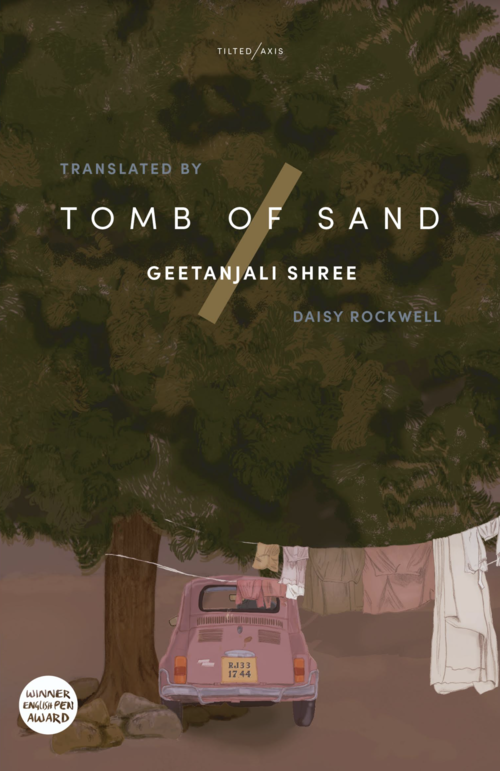

Last week Geetanjali Shree’s novel Tomb of Sand, translated from Hindi by Daisy Rockwell, won the International Booker Prize. Many media headlines have focused on this being the first time a novel by an Indian author has won the prize, or the first time a book originally written in Hindi has won the prize, but the most significant “first” for me is that this is the first time its publisher, Tilted Axis Press has been recognised by the International Booker. It has always seemed to me a glaring omission that no Tilted title had ever made the longlist, so it was encouraging that in 2022 the press exploded onto the longlist with not one but three titles (the other two were Norman Erikson Pasaribu’s Happy Stories, Mostly, translated by Tiffany Tsao, and Sang Young Park’s Love in the Big City, translated by Anton Hur).

There is something particularly special about this win: Deborah Smith, founder of Tilted Axis Press, won the first Man Booker International Prize (as it was then called) in 2016 for her translation of Han Kang’s The Vegetarian. The year before that, Deborah had set up Tilted Axis Press, extending her work bringing literature of Asia into English by publishing as well as translating. Yet although Deborah herself was shortlisted again for the prize (in 2018, for her translation of Han Kang’s The White Book), all the eligible titles submitted by Tilted Axis had been overlooked until this year. Is this because none of them had been “good” enough until now? I don’t think so. Rather, I think it shows the importance of the panel, who is on it and what their outlook is.

I have to put my hands up and say that while I’ve read Happy Stories, Mostly and Love in the Big City, I haven’t finished reading Tomb of Sand yet. So my thoughts here are not review-type reflections on the book itself, but rather thoughts on the importance of its win. When I started reading Tomb of Sand in December (yes I know, I’m reading it VERY slowly), my eight-year-old daughter asked me what I was reading. I explained that it was a novel originally written in Hindi, a language of India, by a writer called Geetanjali Shree, and that a translator called Daisy Rockwell had written it all over again in English, and that’s how I was able to read it. Wide-eyed, she said: “But that’s AMAZING!” How often do we forget this? It is amazing that literature from other cultures is accessible to us because of translation (and, more specifically, because of translators), and it’s amazing that there are presses out there who will seek out books that might otherwise not make their way to us, so that the literature that reaches us isn’t always by the same people from the same places.

Tilted Axis Press is committed to this diversity of literature and voices making it through, working to change the legacy of colonialism and imperialism that calcifies our understanding of “world literature” within marginalised or exoticised stereotypes. In a mission statement on the Tilted Axis website, the press describes its process as “an ongoing exploration into alternatives – to the hierarchisation of certain languages and forms, including forms of translation; to the monoculture of globalisation; to cultural, narrative, and visual stereotypes; to the commercialisation and celebrification of literature and literary translation”. This bold statement is intertwined with a public commitment to working with translators of colour and to gender balance, and offers a direct challenge to the publishing industry, drawing attention to hierarchies of language, genre and background, and to the cultural contexts that focus on profit or on the consecration of a handful of authors.

It is a truth not often acknowledged that prize lists are predominantly white and eurocentric: while judges are of course concerned with finding the “best book”, I believe that falling back on this justification without questioning what it means risks overlooking the ways in which we have been conditioned to respond to literature, and the criteria on which we might unconsciously judge its merit. The reference in Tilted Axis’s mission statement to the “monoculture of globalisation” explicitly points out the inherent problems masked behind a neo-liberal concept such as “globalisation”, which can serve to obscure the multiple daily violences inflicted on non-dominant languages and cultures. So this Tilted win is important not because of a need for data-driven diversity initiatives, but rather because it shakes up the way in which we approach and think about literature, dismantling our preconceptions of what makes the “best” books. It shows others in the chain of commission and production that these books can be recognised, can be worth taking a risk on, and it shows us as readers that we do not have to reach only for what is familiar.

Warmest congratulations to Geetanjali Shree, Daisy Rockwell, and all the team at Tilted Axis Press: long may you continue to challenge, to inspire, and to tilt the axis of “world literature” from the centre to the margins.