Translated from Spanish (Mexico) by Suzanne Jill Levine (Seven Stories Press, 2020)

This collection of short stories from acclaimed Mexican author Guadalupe Nettel is the second release from the new UK imprint of Seven Stories Press. In it, Nettel blends the familiar with the strange in a body of stories that offer a kaleidoscope of unexpected perspectives: a photographer’s fascination with an overlooked body part becomes a dangerous obsession, an awkward date is observed from the building across the street, a man’s regular visits to his local botanical gardens have devastating consequences for his marriage, an adolescent girl is foiled in her quest for True Solitude, an olfactorist follows the trail of a desperate woman, and a young woman develops a nervous habit that leads her to a mental asylum.

The locations for the stories are disparate – from Mexico to Japan by way of Paris, with some offering no obvious location – and characters are estranged not only from those around them, but also within and from their own bodies. In the opening story, “Ptosis”, a photographer’s fascination with eyelids leads to him becoming the official “before and after” photographer of a leading cosmetic surgeon. Eyes are viewed in close-up throughout this story, in poetic phrases that throb with the threat of permanent damage. People with imbalanced, misshapen or droopy eyelids pass through the photographer’s doors, each looking more “normal” in the second photo shoot until he comes to the disquieting realisation that “if you look closely, especially when you’ve seen thousands of faces amended by the same hand, you discover something atrocious: somehow, they all look the same. As if Dr. Ruellan had imprinted a distinctive mark on each patient, a faint but unmistakeable stamp.” The photographer becomes obsessed with one particular patient, whose imperfect eyelids come to represent the source of her individuality and attraction; his mission then becomes to save his muse from going under Dr Ruellan’s knife. At once an edgy exploration of insecurity and voyeurism and an indictment of homogenised notions of beauty, this is an excellent story to start the collection.

In “Bonsai”, an obsession with botanical gardens and the different plants in a greenhouse drives a wedge between an apparently happily married couple. Taking care of plants is a commitment, says the gardener at the greenhouse, but the narrator finds himself able to care for only one kind of plant – his cactus-like self, rather than his “climbing vine” wife. Once he identifies their plant characteristics, their fundamental incompatibility becomes clear to him: he is an outsider, defensive and prickly, while she has a “quiet way of infiltrating any space and taking possession of my life.” The story is narrated with the biological precision of a botanist, a kind of seemingly scientific observation that is echoed in a more disturbing way in “Petals”. In this story, an olfactorist who observes and analyses the traces women leave behind in bathroom stalls becomes obsessed with a woman he calls La Flor. He identifies La Flor as exceptionally delicate, a woman whose traces indicate an ephemerality and state of decay that bring him to a near-climax: “It was as if her whole life had slipped out from deep inside her. The image struck me as so intense that I had to raise my face for a few seconds to breathe.” It’s deeply and ingeniously uncomfortable how he follows this vulnerable woman, learns about her from the traces she leaves behind in toilet stalls, and arrives at a state of teeth-grinding ecstasy when he is finally present for “the moment of production”, listening to her urinate in a neighbouring stall. This tense and disturbing story was, for me, the stand-out one of the collection (particularly its ending, which I shall leave you to imagine or discover for yourself).

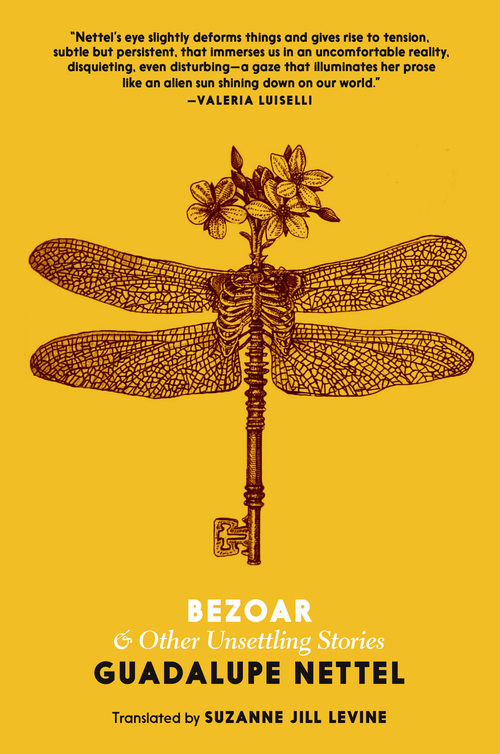

The title story, “Bezoar”, takes its name from a myth about a long-haired woman holding a gemstone. According to this legend, in a faraway place there existed a stone or ball of hair with healing powers – the bezoar. The bezoar was “the remedy for all poisons and also the stone of perfect calm”, and though here it is used to represent the relief felt by a compulsive woman when her compulsion is satisfied, it also stands as a motif throughout all of the stories, in which protagonists search for a sense of calm and fulfilment – which usually remains tantalisingly out of reach, or is realised in a way that is not entirely as they expected or hoped.

The narrator recounts – in a therapy diary that she writes from her room in an asylum – how, as an adolescent, she became obsessed with the hair follicles she observed when she pulled out strands of her hair, and thus began a traumatic lifelong habit of removing entire patches of hair from her scalp: “Like the survivor of a shipwreck, dragged by the whims of the waves, I let myself be swept along by habit. I constantly felt humiliated, victimized by an abuse I inflicted on myself without knowing why.” Rejected by those around her but eventually making a career as a model (which she sabotages by her persistent self-inflicted shedding of locks), she falls in love with the only person she can truly connect with – someone who has an obsession that rules his life in the same way her hair removal governs hers. But he swiftly comes to represent her worst fears, as their co-dependent relationship spirals out of control; as is the case elsewhere in these stories, the tension in the narrative mounts towards a seemingly inescapable climax.

Many of the stories in Bezoar and Other Unsettling Stories are about love, or at least about relationships, but always from a perspective of subversion or alienation. “Unsettling” is the perfect word to use in the title of the collection, but the stories are not unsettling because of any dabbling in supernatural or horrific subjects. Rather, they are unsettling because they are only a whisper away from very recognisable situations, and reveal how uncomfortably close any one of us might be to enacting or being on the receiving end of the variously defensive, pitiful or harmful behaviour of Nettel’s protagonists. That the stories are narrated in the first person makes this even more unsettling: we are invited to view events from the perspective of disturbed and often disturbing individuals, outsiders who maintain a delicate balance between beauty and depravity. In terms of form, the stories are very well contained and developed. Nettel is judicious with her use of words (in both precision and quantity), and the translation by Suzanne Jill Levine is appropriately spartan and evocative (I think my favourite line of the translation was this: “my mother ran about from one end of the room to the other like a fly looking for an escape route and smashing against the windows instead”). There is a consistency in the translation, which I imagine mirrors a consistency in the original, for using reserved, almost detached language, avoiding anything theatrical or too emotional. This is an unsettling collection indeed, but one which finds beauty in extraordinary places.