Charlotte Coombe has been translating for over twelve years: having started out translating creative texts in gastronomy, the arts, travel and tourism, lifestyle, fashion and advertising, her love of literature drew her to literary translation, with a particular interest in women’s writing. Her translation of Margarita García Robayo’s Fish Soup (Charco Press, 2018) is currently shortlisted for the prestigious Society of Authors Premio Valle Inclán 2019, and she was recently awarded a PEN Translates award for her forthcoming translation of García Robayo’s novel Holiday Heart (Charco Press, 2020). She has also translated poetry and short stories by authors such as Rosa María Roffiel, Edgardo Nuñez Caballero and Santiago Roncagliolo, published online by Palabras Errantes.

How do you find new works to translate, and how do you choose publishers to work with? In particular, what drew you to the work of Margarita García Robayo?

It was Charco Press who came to me with Margarita García Robayo’s work. They discovered her writing and bought the rights, then came to me because they felt I might be interested in translating her, and as soon as I read ‘Waiting for a Hurricane’, mine was an emphatic ‘YES PLEASE’. This just goes to show the important role that small independent presses play in finding new voices, often never translated before into English.

I hear about new works to translate mostly on the internet, via my various networks, or by authors contacting me (which is happening increasingly now). I cannot emphasise enough how useful social media can be when it comes to finding new books, new authors, finding out what publishers publish and are looking for, connecting with editors, writers, poets, and of course translators. If you are connected to a network of authors in all your languages, you hear about their new books and you hear about the authors that they like. I recently heard about Marvel Moreno because Margarita García Robayo posted about her on Instagram. Moreno was an author who in her lifetime was something of a literary legend in her native Colombia, and was published in French and Italian, but despite all that, she was never translated into English and never really received the recognition she deserved. I saw Margarita’s Instagram post, and this led to a series of events where I tried to find more of Moreno’s work online and in print, and found it lacking. I chased this up and now have permission from her daughters, the rights-holders, to translate her work. I’m working with my colleague Isabel Adey to bring her writing into English, and that all came from an Instagram post: I would never have come across her otherwise. And I always say that for me, Twitter (as well as being a huge source of procrastination – it’s an absolute time sponge, I swear) is like opening a door to a room of translator colleagues and saying, ‘Hey, what do you think about this?’ Or ‘What does this Spanish word mean?’ and getting instant replies. Social media is very important, I personally think, in combatting freelance isolation and in keeping in the loop.

What do you perceive as the greatest challenges regarding gender bias in translated literature, and how does this affect who gets published and who gets translated?

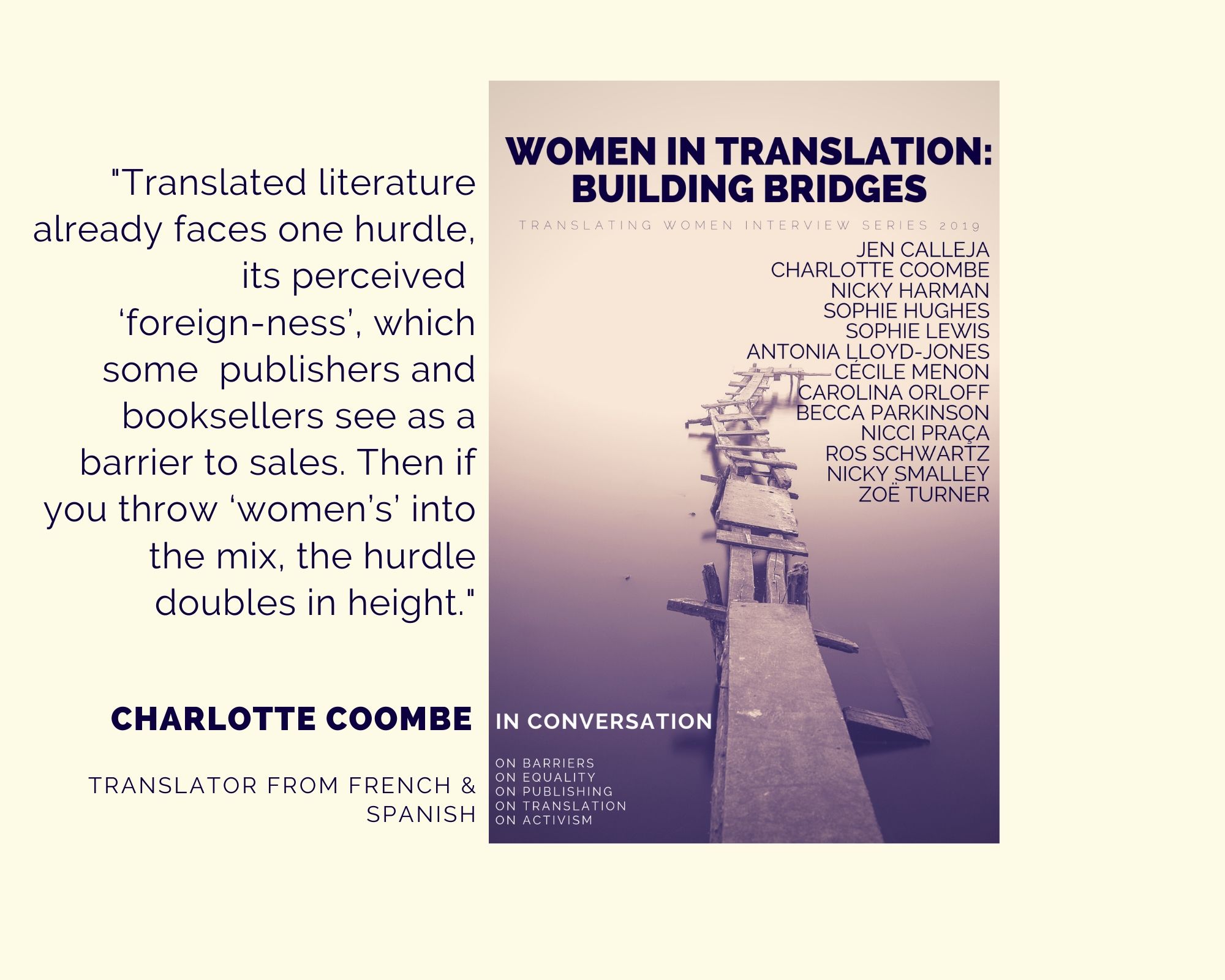

Translated literature already faces one hurdle, its perceived ‘foreign-ness’ which some (not all) publishers and booksellers see as a barrier to sales, and then if you throw ‘women’s’ into the mix, the hurdle doubles in height. This is changing gradually. But the way the publishing industry is set up is obviously biased towards men – gender bias is entrenched into every aspect of life, as any good feminist will know – and anything that is not written by a white, heterosexual, anglophone male immediately falls into a separate ‘category’. I feel like this gender bias stretches into translated literature as well. However, there are a lot of women and men out there championing great new authors who deserve to be translated.

What do you think might usefully be done to respond to and overcome such biases?

There are plenty of things that we as readers, and as translators can do: find books by amazing bad-ass women in whatever language and seek out amazing bad-ass publishers who are keen to overcome the bias in translation/publishing. There are a growing number of them (Feminist Press, Tilted Axis, to name a couple). Submit pieces by these authors to online journals and get people talking about them. If all else fails, start your own indie press. I feel like there is definitely space for this in today’s industry – presses like Charco Press started doing what they are doing because nobody else was doing it. This is one of the joys of the world we live in. If it’s done right, any ‘niche’ will become less ‘niche’. I think pledges by certain presses to only publish women for a year, and that kind of thing, is helpful. It gets more books by women out there, and raises awareness about the inequality. There is also Women in Translation month, which of course you know about, started by Meytal Radzinski – where people pledge to read women writers in translation for just the month of August. Although these are kind of activist measures, they do gradually help to turn the tide. The more we talk about books by women or translated by women, the more mainstream this thinking becomes. And more normalised, less ‘niche’. Women are not niche. But women’s writing is perceived as such. I think the way we talk about fiction is important – saying ‘women’s fiction’ or ‘translated fiction’ immediately pigeonholes a book, and immediately creates a wall. There is no such thing as ‘men’s fiction’, so why should fiction by women be labelled ‘women’s fiction’? There is only one criterion for fiction really, and that is, is it any good? We need everyone to stop talking about fiction like this, but it seems to be the natural inclination still, within the book industry.

You won your second English PEN award for your translation of Margarita García Robayo’s next novel: what is the significance of this in helping to promote your work as a translator, and to what extent would you consider the work of organisations such as English PEN as activist?

It’s good to feel that the book you’re working on is believed in by someone already. The exposure from receiving a grant like this helps to get my name out there, plus it means that the publisher receives the funding to do the books they want to do, and pay their translators the TA recommended rates, so it is really positive. English PEN list you on their World Bookshelf, so that’s some more exposure there, and all of that helps to promote my work as a translator. Aside from helping to fund the publishing of different, sometimes controversial perspectives, English PEN also campaign in so many ways for freedom of expression, so their work is fundamentally important for supporting writers around the world and for standing up against injustice.

Do you think that Spanish-language women writers are well represented in translated literature? What/ who would you like to see gain greater recognition?

I think that they are fairly well represented, in terms of the number being published, although there is always scope for different forms of representation within this language group. There has been a real wave of new female voices from Latin America in particular, who have been translated in recent years and received critical acclaim. I am thinking of course of Lina Meruane, Samanta Schweblin, Ariana Harwicz, Mariana Enríquez, Gabriela Cabezón Cámara, Carmen Maria Machado, Brenda Lozano, and of course Margarita García Robayo, to name but a few. Being a translator from Spanish, rather than say, a Baltic language for example, you have a lot of other translators ‘chasing’ the same amazing books and authors, so it can be slightly more competitive in that regard. But it is also good because you can ride the wave of popularity of Latin American authors, and throw new authors into the mix, who people might not have heard of yet. There is always room for more amazing writers. I mentioned Marvel Moreno earlier; Isabel Adey and I have been translating her short stories and recently published one of them, entitled ‘Self-criticism’, online with Project Plume. We have also just been granted a three-week residency at the prestigious Jan Michalski Foundation in Switzerland, so Bella and I will be spending most of June working on that, in tree house cabins near Lake Geneva!

I am currently working on a couple of translation samples for Spanish authors, and pitching a co-translation of a Haitian French author with another colleague of mine. I also recently translated a sample of Lucia Baskaran’s book Cuerpos Malditos (Cursed Bodies) – wow, what a book, I loved it so much. She is a very bold writer, dealing with sexuality, family ties and identity, with a fast-paced kind of prose: this book is a real page turner. Plenty of twists and turns in that book. I’d love a publisher to pick that one up – she deserves to be read in English and has wide appeal, I think.

Can you tell me a little about the new Margarita García Robayo book you’ve just finished translating (coming from Charco Press in 2020)?

It’s a novel this time, entitled Tiempo Muerto (Dead Time/ Wasted Time), which will be published in English as Holiday Heart. It’s a book about the breakdown of a marriage, essentially, but it also deals with themes of migration and integration, and touches on issues of racism and racial stereotyping of, and by, Latin Americans. The novel has a lot of Margarita’s characteristic style, her biting wit, her insights into the human condition, and has been pretty challenging to translate. Her prose is deceptively simple. I’d read a sentence and think: OK, I’ve got this. But when I set about translating it, breaking it down, and building it again, I realised she’s chosen her words so very purposefully and precisely, to conjure up a particular image or convey a particular feeling. Her writing is never just about one thing; it has so many layers. I am fully inside her universe now, having translated Fish Soup, and now Holiday Heart, so that helps to find the voice.

Read the Translating Women review of Fish Soup here.