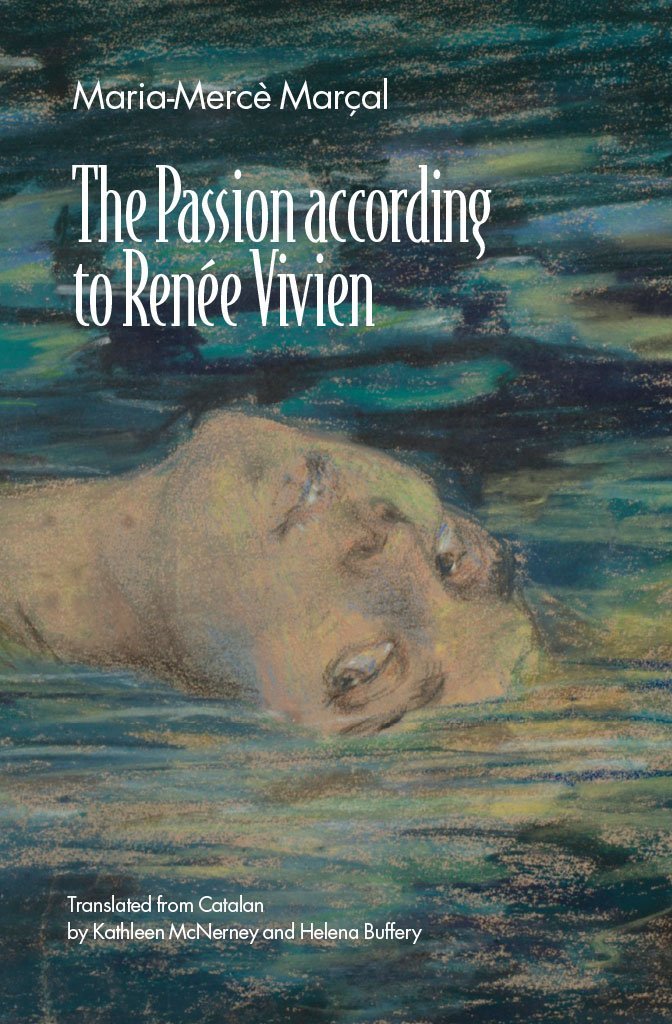

Translated from Catalan by Kathleen McNerney and Helena Buffery (Francis Boutle Publishers, 2020)

This is a very different kind of novel from those I normally read for Translating Women, and will be a treat for anyone who enjoys creative biographies. The Passion According to Renée Vivien represents a literary project to uncover the hidden life of Renée Vivien (the literary pseudonym of Pauline Tarn). Renée Vivien was an English-born poet who wrote in French in the early twentieth century, whose poems are particularly notable for their explicit revelations about her amorous relationships with women, who lived in a “palace of pain” and longed to escape from life, and whose legacy has been “demolished by the victorious blows of mediocrity and stupidity.” Originally published almost thirty years ago, The Passion According to Renée Vivien is a ground-breaking work in Catalan literature, taking on the traditional “academy” from the marginalised perspective of a woman writer – and not just a woman, but a woman who openly proclaims her love for other women, a poet whose name “shines … with its own light amid a tradition that certainly existed but only underground, the victim of invisibility and silence.”

Herself an openly feminist and lesbian author and activist, Maria-Mercè Marçal became obsessed with the idea of lifting Renée Vivien out of the exile which is “the common lot of poets” – an obsession that she transfers to one of the main active voices of the text, Sara T. The decision to create fictional biographers is a clever one: this is no dry, objective account of Vivien’s life, but rather a vivid, impassioned quest to uncover her mystery and her legacy. The Passion According to Renée Vivien is full of beautiful aphorisms (“After all, perhaps glory is just a posthumous form of love: the only form with the capacity to raise the dead”), and Marçal sets out to give voice to an overlooked figure from recent literary history by writing a book about “women who, like me, yearned for deep-rooted changes in the world.”

This polyphonic text is part documentary, part biography and part love song to its subject. We discover much of Pauline’s life through the eyes of Sara T., a 1980s Catalan documentary maker who becomes obsessed with giving voice to Pauline, and in particular Sara reveals the difficulties of piecing together all the details of Pauline’s life to make a coherent whole. The other main source of information is Salomon R., a museum curator, and we also have letters from Pauline’s lovers, as well as a more objective and omniscient third-person narrator from Pauline’s own era, through whom we gain insight into her personal circumstances through observations of her entourage and conversations between courtesans. Though in some ways contemporary readers might find the main narrative’s milieu less recognisable because of the relatively privileged lifestyle it details (for example, one character’s great dilemma regards her “unresolved doubts” about an ivory statue in a museum, and Renée herself “had the fortune to be able to torment herself with only metaphysical problems”), the timeless and universal qualities of love, loss, desire, jealousy, sorrow and despair prevent the text from feeling dated or unrelatable.

My over-riding impression of the translation was that much time, energy and (if I may borrow from the title) passion has gone into making this work available to English-speaking audiences: it’s clear just how much both translators care about this project. The writing is lyrical and eloquent, almost old-fashioned in its language choices, but not dated. It evokes a time of formality in turn-of-the-century Paris, and manages to sustain a formal and authentically period-appropriate narrative style throughout its 350 pages. This formality is also partly owing to a delicate attention on the part of the translators to favour terms that have French etymology, reflecting through this choice Pauline’s own writing “against” English. In the whole book there were only a couple of instances when I thought something more modern might have crept in, but this may well be my own ignorance of when expressions became current in English – or it may reflect potential anachronisms in the original Catalan. Overall, there was something very nostalgic for me about reading this book: its turn-of-the-century style and references to 19th-century writers and culture took me back to my years studying French literature, and locating much of the narrative in Paris is always a way to tug at the nostalgia for me. All it takes is the street names and in my mind I’m already there – so my only regret in that sense was the anglicisation of some of the street names – a number of the more recognisable ones remain in French, but elsewhere there are references to, for example, “Vendôme Square” and “the boulevard of Paix”, which for me snapped the nostalgic connection. But that’s an entirely personal reaction, and for readers who don’t know French – or don’t know Paris – then this might, conversely, bring them closer to the text, particularly given the strategies of writing “against” English that I mentioned earlier.

I’ll leave you with a little scoop that for me was the most fascinating thing about this novel: thanks to an interview with translator Helena Buffery (which you can read here in full next week), I discovered that the final chapter of The Passion According to Renée Vivien is made up entirely of fragments of Renée Vivien’s poetry. This section is breathtakingly beautiful, and the book is worth reading for this alone – not only its beauty, but also the skill of weaving together the (French) fragments to make a narrative (in Catalan) that is now translated into English. Within the fictional biographer’s task, we are told that “her verses were the autobiography of her soul”, and so it feels appropriate to give the last word to Renée Vivien, via Marçal, in a rendering by Buffery and McNerney:

“I am of those laid low by light. Under the implacable face of day, memories devour me like abject vermin. And at dusk when I hear the groaning of the unfortunate land, I have felt in excess the horror of having been born. Who, then, will bring me the hemlock in their hands? Night slithers, slowly and subtly, toward the opal of the hill. The soul resuscitates in the tenebrous shadows.

… I will hurl myself into your eyes, where sadness rhapsodizes.

… Here, words do not hurt, Let us keep the doors closed. Souls without hope have the solitary pride of islands.”

Review copy of The Passion According to Renée Vivien provided by Francis Boutle Publishers