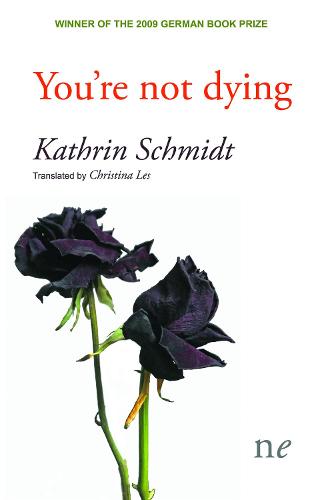

Translated from German by Christina Les (Naked Eye Publishing, 2021)

Kathrin Schmidt’s You’re Not Dying is a prize-winning best-seller in Germany, where it was first published in 2009, and today the first English translation (by Christina Les) is published. The release of You’re Not Dying also represents the first foray into translated literature for independent press Naked Eye, but the “firsts” aren’t the only thing of note about You’re Not Dying. This is the story of a woman waking from a coma to find that she cannot move her right side, cannot speak, and has lost many of her memories. Helene has suffered a stroke, and You’re Not Dying is the story of her readjustment to life as a disabled person. In the many books I’ve read in the three and a half years since embarking on this project so few have dealt with disability, which in general is under-represented in literary fiction. You’re Not Dying approaches its subject sensitively, but with a ferocity of emotion that felt to me very realistic (indeed, it is based on the author’s own experience), tapping into deep-seated fears of disempowerment, dependence, and the way life can be redefined in an instant.

The narrative is arresting from the very first pages, with Helene waking up and trying to make sense of where she is, and what has happened to her. The sense of disorientation, dulled by medication, is quietly terrifying: “She’s got something in her mouth. She can’t close her mouth at all. She wants to ask the woman what she can see stuck in her mouth, but the woman takes her arm and connects it to a tube. Some kind of network? So they can control her remotely?” Helene learns that she has been in intensive care, in a coma, but the details of the damage to her body trickle through slowly, in the same way that her memories – both good and bad – return intermittently: “Her memories drag themselves along, slowly and deliberately dragging what used to be along with them.”

Helene’s mind can formulate words, but when she tries to articulate them in any kind of understandable configuration she becomes confused, the words stubbornly refusing to follow the order into which she has painstakingly arranged them in her head. That her mind is still working at her usual speed while her speech fails her is communicated powerfully, as is the loss of her days (“Twenty minutes have passed. Twenty minutes of life.”) Helene has to deal with the abjection of needing help to go to the toilet and to get dressed, of being fed or, as she gets a little movement back, of spilling food down her face and clothes when she tries to feed herself, and of realising that she has a near-constant trail of saliva dangling from her mouth that she can neither control nor wipe away.

The depiction of dependence and the stripping of dignity that physical suffering brings is deliberately uncomfortable, but one of the most stuff-my-fist-in-my-mouth horrifying episodes was Helene’s day release back home, when her husband Matthes wants to rekindle their former passion and Helene cannot physically or verbally tell him she does not consent. Indeed, as Helene starts to piece back together the various identities and relationships that defined her pre-stroke life, she remembers that she had been on the point of leaving Matthes; not only this, but she had begun a hesitant though passionate relationship with Viola, a transgender woman whose own emotional traumas and social othering are also carefully examined as Helene tries to reach a place in her memory that will explain the broken recollections of Viola to her. Though Viola’s story is interesting in its own right, the most emotional aspect for me was the way in which Helene remembers powerlessly, unable to let Viola know what has happened to her and knowing that, given the way she parted from Viola after their last meeting, her silence will be taken for a lack of care.

Christina Les translates You’re Not Dying with sensitivity and pathos: I have long believed that empathy is one of the keys to good translation, and Les demonstrates this in bucketloads. Her translation allows Helene to speak – in her newly broken way, of course – and to go to the limits of her memories, sadness and anger. The translation is written extremely carefully, but without seeming laboured: from individual word choices down to cadence and syntax, Les has perfectly pitched this multi-layered story of extraordinary events and everyday trauma. Perhaps what I appreciated the most in You’re Not Dying was the refusal to make it a redemptive narrative: Helene’s misfortune does not somehow make her a nicer or less cantankerous person, though there are some amusing episodes when we gain insight into her unwillingness to suffer fools gladly. She does not find that disability gives her a better perspective on the world, a better experience within it, or a renewed hope for the future. Her relationships do not magically mend or become less complicated, and neither is there a miraculous recovery: Helene’s progress is faltering, and there is no guarantee that she will ever return to the life she had before her stroke. Though I preferred the first part of the novel (Helene’s realisation of and reaction to what has happened to her), to the second part that goes into more detail about her life before the stroke, in the last paragraphs we finally witness the point at which Helene’s life changed forever, and it was worth the wait.

Review copy of You’re Not Dying provided by Naked Eye Publishing