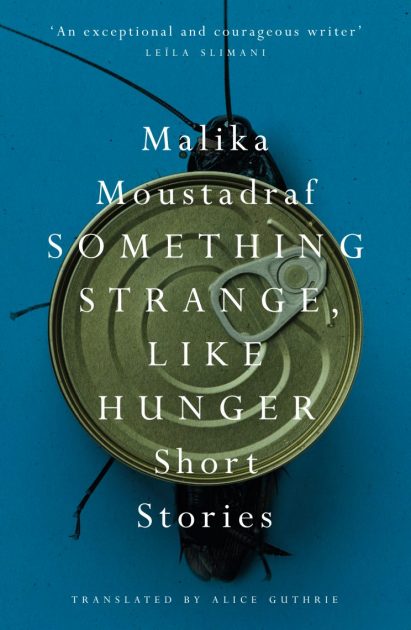

Translated from Arabic (Morocco) by Alice Guthrie (Saqi Books, 2022)

Something Strange, Like Hunger is the posthumously published work of Moroccan feminist Malika Moustadraf. A collection of fourteen short stories, it explores themes of femininity, sexuality, taboos and sociocultural restrictions, and represents an important project of “literary recovery” as detailed by Guthrie in her translator’s note at the end of the text.

The collection opens with ‘The Ruse’, in which two sisters are discussing the imminent marriage of one of their daughters. The mother of the bride-to-be is planning to get a “virginity certificate” for her (unbeknownst to her, far from virginal) daughter. From the outset, Moustadraf pulls no punches about the experience of women in the culture her stories describe, showing misgoynist attitudes to be so deeply entrenched that many women share and perpetuate them: the mother ends up ” wailing and cursing the day she’d given birth to a female child, in mourning for the day when girls were buried alive at birth.” The male characters say even more aberrant things that trivialise women’s suffering and overtly subjugate them, and throughout the stories these dangerous attitudes and practices towards women intensify: the woman taken to a hammam to have her body hair removed, hands henna-ed and eyes ringed with kohl so that she can be married off (or, as she more accurately describes it, “sold off”), the woman doctor summarily dismissed because “women aren’t cut out to be doctors”, the woman slapped by her husband as soon as they are married, so that she knows he has dominion over her, and the casual misogyny of violently silencing claims such as “a woman loves an evening beating from time to time, before she goes to sleep, and for you to pull her hair every once in a while – these customs have been ingrained in women since the Stone Age.” There is a simmering rage in Moustadraf’s work that is deftly communicated in Guthrie’s translation: these incidents are presented without partisan comment, but in a way that makes clear how hateful and harmful they are.

One aspect marketed as a selling point is that Something Strange, Like Hunger includes the first ever trans character in Arab literature (another first of the collection, pointed out by Guthrie in her translator’s note, is the first literary depiction of cybersex in Arabic). This trans (or possibly intersex – the lack of insistence seems quite deliberate and open to interpretation) character appears in the story ‘Just Different’. The main character is a prostitute who, in the course of the story, recounts a series of humiliations they have suffered at the hands of their community and their family, all of whom are unaccepting of their decision to live as a woman. If they carry a razor blade, it’s because of the day a group of bearded men who wanted to “clean up society” shaved their head – an echo of the time their father had marched them to a barber shop and inflicted the same “corrective” punishment on them. This humiliation is explicitly tied to religion, as they are subsequently forced to recite from then Quran before writing out “I’m a man” a thousand times. The impossibility of being other, of deviating from a violently socialised gender norm, is in sharp relief here as elsewhere in Moustadraf’s stories, and the importance of this story is evident in the fact that the title of the collection is taken from a particularly beautiful line from the protagonist’s past. This is the moment of the protagonist’s sexual awakening, in which the teacher asks them to stay behind after class and wipes sweat from their brow, “eyes blazing with something strange, like hunger”. The implicit yearning and impossibility to voice desire is especially delicate in a story of such violence, and I love that this was chosen for the UK title (the collection was also published by the Feminist Press in the US as Blood Feast, which is the title of another short story in the collection).

The translation by Alice Guthrie blends informal register and vocabulary (things get “sketchy” for the protagonist of ‘Just Different’, for example) with evocative expressions from the original language (“As the saying goes, ‘Throw a handful of salt in her eyes and she won’t even blink’”), and superb use of imagery (I must give a mention to one of my favourite images: a decrepit bus moving “like a time-ravaged tortoise”). The stories are then followed by an extended translator’s note, in which Guthrie does several things: first, she draws attention to Moustadraf’s life and legacy, and the importance of this work being translated and circulated. It is particularly notable that Guthrie points out a common response to biographies of women writers from the global south: these, Guthrie notes, “are very often expected to inform and interweave with their fiction. It is much harder for these writers to have their writing received as feats of pure imagination than it is for others, especially white cis male writers.” This is a notion I’ve been coming up against increasingly lately: how women writers are so often asked what it is to write as a woman, or how their fictional work is assumed to be in some way autobiographical. Guthrie delicately draws attention to this without moralising, but underlining the importance of reading Moustadraf’s work for what it is, rather than for what we can infer about the author through reading it.

Guthrie goes on to detail the research that she undertook for this translation, and the people and communities who helped her – this is all the more fascinating after reading the translation with no prior idea of just how much painstaking linguistic and contextual research went into its preparation. Finally, Guthrie discusses some of the linguistic choices she made, in terms of both general approach and specific detail. The inclusion of such a focused and engaged account of the translation process is an excellent example of the translator’s visibility: though this concept is often discussed in terms of the text itself, I find it more useful to consider it in terms of paratexts such as this translator’s note. I don’t want to imagine that a translated text arrived with me neatly in English, with no agent in between the original and the translation. Nor do I necessarily believe that the “best” translations are the ones that never remind us that they are a translation. However, more than anything I want to imagine the translator as a part of the process of this book coming to me: I’m interested in why they chose to champion this book, how they set about completing the translation, the challenges they faced along the way… This can come to us in the form of literary events, interviews, or translator’s notes, and Guthrie’s note on Something Strange, Like Hunger is exemplary – in fact I enjoyed it just as much as the book itself, and came away from it feeling that I understood the stories on another level.