Translated from the Spanish by Achy Obejas (And Other Stories, 2018)

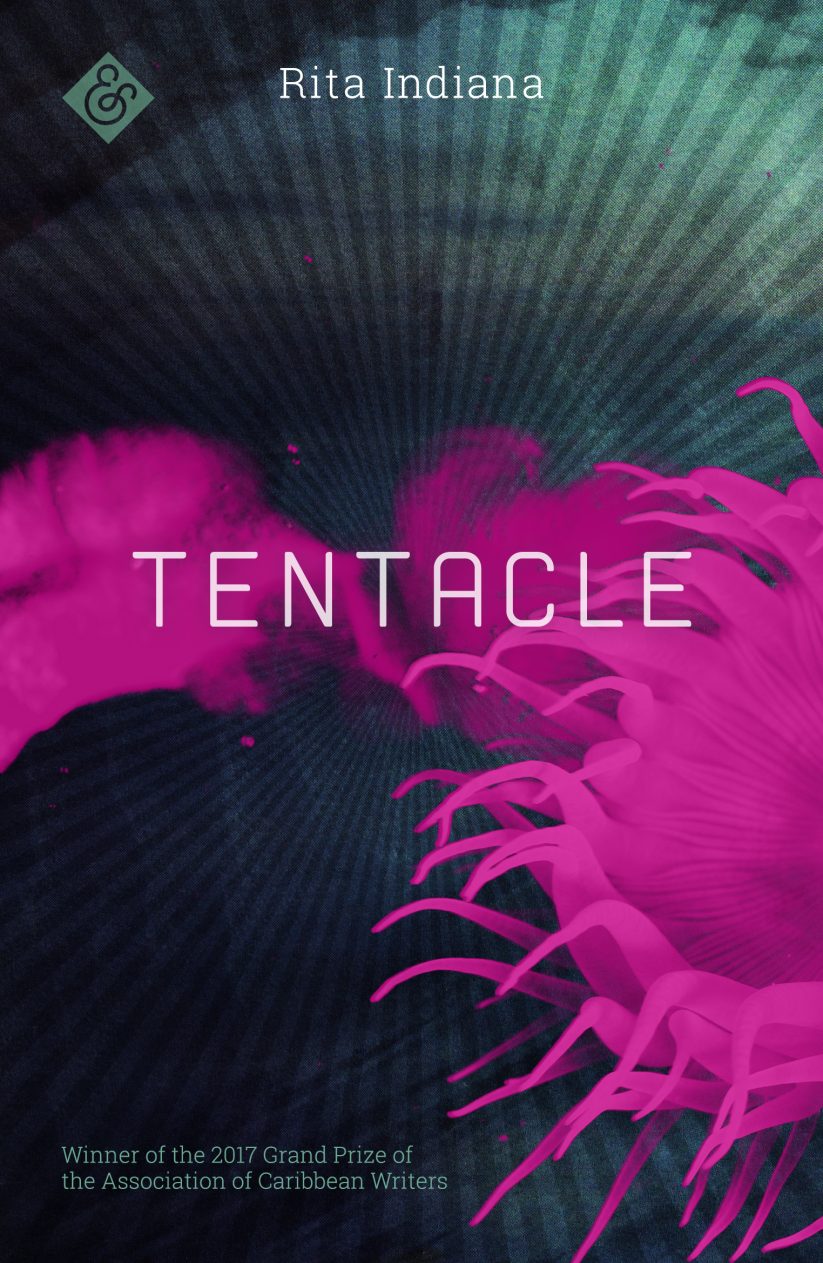

Tentacle was the final book released by And Other Stories in the Year of Publishing Women, and it smashed all of my expectations: a psychedelic voodoo Caribbean Genesis story collides with science fiction and eco-criticism in a furious explosion of colour and poetry, presided over by a sacred anemone. If you want to put a label on it, then Tentacle is probably best described as “experimental fiction”, but this doesn’t even begin to do it justice: it is both historical and contemporary, spiritual and pragmatic, science fiction and art – in short, as uncategorizable as it is exceptional.

In a dystopian mid 21st-century Dominican Republic, an ecological crisis has turned the sea to sludge and killed most ocean life. We are in a time of advanced technology, when headsets function as a virtual-reality version of the internet, and yet humanity has regressed to some of its basest impulses; a modern-day plague is sweeping across the Caribbean, and affluent members of society are brutal in protecting themselves from contamination: “Recognizing the virus in the black man, the security mechanism in the tower releases a lethal gas and simultaneously informs the neighbours, who will now avoid the building’s entrance until the automatic collectors patrolling the streets and avenues pick up the body and disintegrate it.” In this post-apocalyptic world where the plague-ridden poor are simply a nuisance for the rich to exterminate, we meet Acilde, androgynous maid to famous psychic Esther Escudero. Picking her way through the pollution and social inequality, Acilde has been plucked from a life of “suck[ing] dicks at El Mirador” because the anemone had foretold that she would be the one to save the world; Acilde thus inadvertently holds the key to future survival, and is part of a prophecy that must be fulfilled. In order to realise her destiny she must become a man, by way of a futuristic sex change far removed from any modern-day medical procedure (carried out with the help of the aforementioned sacred anemone, a contraband artefact protected by Escudero’s henchman), and then travel in time to save her home. Past, present and future lives bleed into one another as characters from the future experience past lives as 16th-century buccaneers or 20th-century artists: time, history, and legacy are simultaneously distorted and clarified, and the protagonists tormented and consoled, by the power of the anemone.

Writing from the near future allows Indiana to make a social comment that never seems moralistic, and which is all the more persuasive for being framed as retrospective. The abandonment of the plague sufferers is reminiscent of current dialogues about refugees and borders, as well as a desensitization towards tragedy that Indiana adroitly reminds us is, in itself, a modern “plague.” The recent past is neatly condensed by the description of Acilde’s room in Esther Escudero’s house as “one of those typical rooms found in Santo Domingo’s twentieth-century apartments, from when everybody had a servant who lived with them and, for a salary well below minimum wage, cleaned, cooked, washed, watched the kids, and attended to the clandestine sexual requirements of the man of the house,” and the Trujillo regime (though unnamed) is described from the future as one that “the foreign press – still – did not dare call a dictatorship.” This didactic comment does not feel forced, as it is all in the context of an environmental disaster that has not (or not yet) happened in real life (there are early references to “the day of the tidal wave” that wiped out half the population). Yet though this may seem futuristic, in a recent interview Indiana stated that this future Caribbean where capitalism and colonialism have brought on humanitarian crises “exists in the present,” and that in viewing it from the future, she offers her readers a “‘safe’ place from which to view them” – and it is undoubtedly one of Tentacle’s great accomplishments that concealed in its futuristic, fictional context is a very contemporary, very real message.

There were ways in which the crux of the story reminded me of Angela Carter’s The Passion of New Eve, but that is not to say that there is anything derivative about Tentacle. Indiana produces a written text with oral qualities, meticulously and thoughtfully constructed but managing to seem effortlessly spontaneous. She draws together religion and voodoo, and reflects the culture of her country while defying tradition: Indiana’s influences and intertexts are multiple and eclectic, as are the possible readings of Tentacle. For all its riotous science-fiction qualities, Tentacle offers a number of social critiques, such as this one on race: “‘Black,’ he heard himself say as he breathed smoke out of his mouth. A small word swollen over time by other meanings, all of them hateful. Every time somebody said it to mean poor, dirty, inferior or criminal, the word grew; it must have been about to burst, and when it finally did, it would once again mean what it meant in the beginning: a color.” It is with reflections like this that Indiana weaves a narrative that is both deeply rooted in the traditions of her country and universally recognisable, and the translation by Achy Obejas – at once lyrical and volatile, evocative and explosive – communicates all the wisdom, energy, and artistic range of Indiana’s work.

The final page – which I’m not going to quote from, or talk about in too much detail, as I want you to enjoy it for yourself if you’re going to read Tentacle – is, in comparison to the rest of the book, quiet, tender, and calm. This is no paradox or accident – Indiana concludes her whirlwind of a story with the quiet at the eye of the storm, as all the worlds, bodies and times collapse in on one another and end together; it is a final page I have read over and over. Tentacle is explosive, innovative, steeped in history but defying tradition, unless it is the tradition that “In the Caribbean we live on the dark side of the planetary brain.” This is an urgent, electric novel, and I highly recommend that you try stepping over to this particular “dark side.”