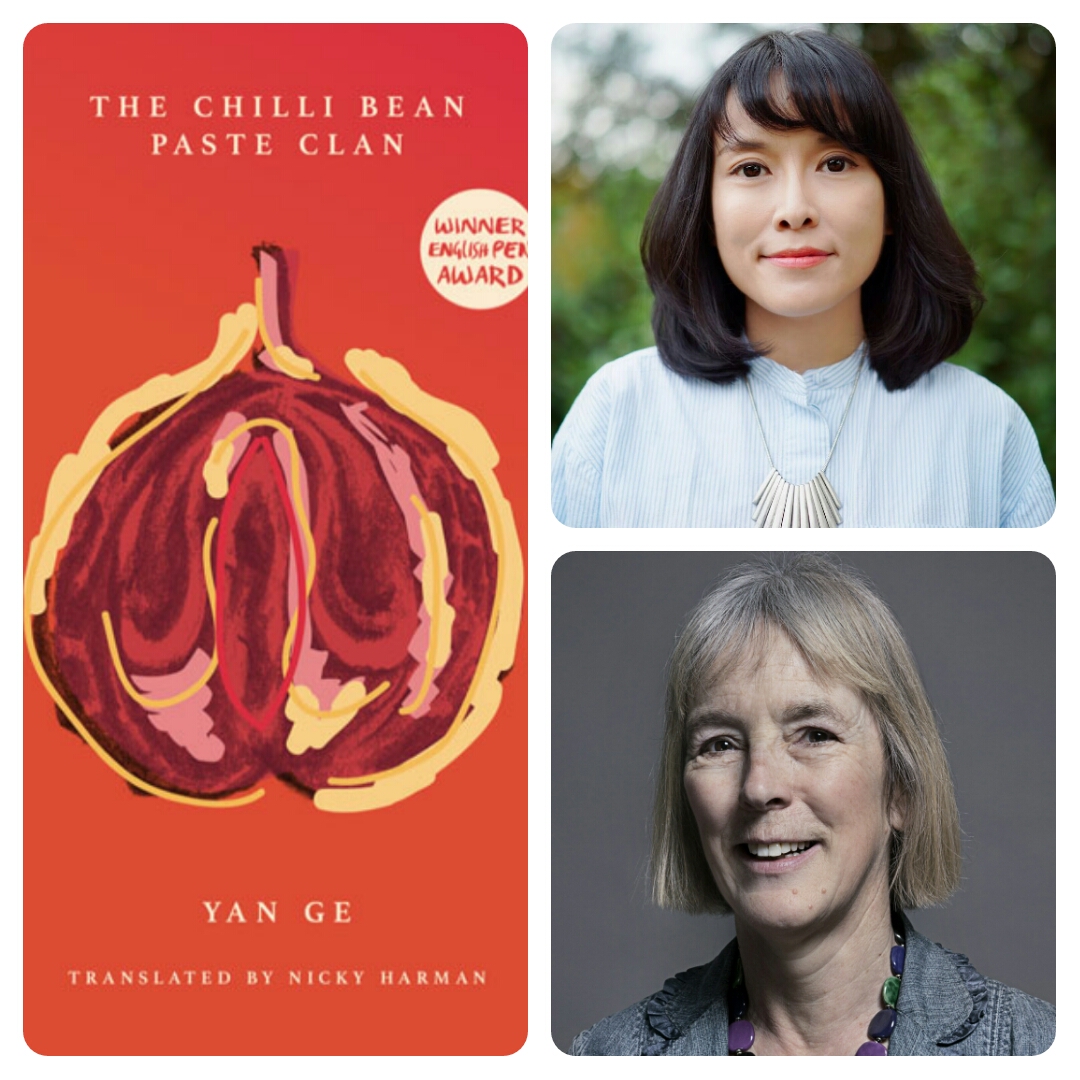

Following on from last week’s review of The Chilli Bean Paste Clan (Balestier Press, 2018), I’m delighted to bring you this exclusive interview with author Yan Ge by translator Nicky Harman.

Set in a fictional town in West China, this is the story of the Duan-Xue family, owners of the lucrative chilli bean paste factory, and their formidable matriarch. As Gran’s eightieth birthday approaches, her middle-aged children get together to make preparations. Family secrets are revealed and long-time sibling rivalries flare up with renewed vigour. As her son Shengqiang (Dad) struggles unsuccessfully to juggle the demands of his mistress, his mother and his wife, the biggest surprises of all come from Gran herself…

NH: I was introduced to your writing by Ou Ning, founder and editor of the influential Chinese-English avant-garde literary magazine, Chutzpah. At that time, 2011, you had submitted chapters 1 and 2 of The Chilli Bean Paste Clan to him, under the title ‘Dad’s Not Dead’, and I translated them. I was immediately impressed by the fresh, direct way you depicted these squabbling, middle-aged siblings and the foul-mouthed philandering Dad, a small-town businessman, who is its (anti)hero. The novel is very different from any of your previous writing, which is both more literary and has more fantasy elements. You’ve written that this shift of style and topic was a deliberate decision on your part and you’ve written very amusingly about your struggles:

‘It took me so long to find the voice of The Chilli Bean Paste Clan, or the voice of Xue Shengqiang (Dad), because it was by no means my natural voice. … I wrote and rewrote the first chapter so many times and none of these worked. …So one day, in Durham (USA), I was on my way back home from the campus and I passed a petrol station. And there came my epiphany! I went in and purchased a pack of cigarettes (White Marlboro, I will never forget). With that I went back home, sat by my table, clumsily lit a cigarette and started to imagine Xue Shengqiang’s life. And that was when it came to me that he cursed a lot. So I wrote another version of the beginning of the story with a cigarette dangling between my lips and tears in my eyes (from the smoke). But it worked. It was his voice and I was very happy. So I actually smoked a lot when I was working on The Chilli Bean Paste Clan. Chain-smoking in the middle of the night. Typing and cursing along with Xue Shengqiang. Sure enough, after I finished the book I returned to being a non-smoker.’

You once said that when you re-read your novel a year or so later, you realised how angry you were when you wrote it. Can you say a bit more about that?

YG: I started writing the Chilli Bean Paste Clan when I was 26 and I had published several books. As a young woman, I struggled to survive in an industry that was more or less dominated by middle-aged men and I was constantly cringing at their behaviour. I suppose a lot of things I saw or experienced made me unsettled and in a sense, disorientated. And to write The Chilli Bean Paste Clan, especially to write it in a different country, was my way of ‘writing up’ or ‘writing back’ to the patriarchal world that I couldn’t really stomach. On the other hand, I was very conscious that a work of fiction should be a neutral ground and the writer’s personal feelings should not dominate the narrative. So one of the principles for the novel was that I should withdraw myself, in particular, my identity as a young woman. But I suppose I can’t really erase myself and my personal emotions, especially they are the things that propelled me to write this novel. So years later, when I reread it, I saw this very angry young woman behind the novel, and her muted anger permeates through the pages. It was both surprising and heartening.

NH: One thing I found most difficult to grasp as I translated the novel was the undercurrents in the relationships between the main family members: Dad and Gran, Mum and Gran (her mother-in-law), and Dad and his brother in particular. To put it simply, I failed to pick up on some of the hidden hostility. Some examples: In the first chapter, Mum and Dad are interrupted in bed by a phone call from Gran. Mum asks Dad: ‘你妈打电话来又什么事?’ My original version was a neutral: ‘What’s your mother on about now?’ You pointed out to me that she’s being deliberately offensive about the mother-in-law she detests, by referring to her as ‘your mother’ instead of ‘Mother’. (In the traditional Chinese family, the woman becomes part of her husband’s family, so his mother is her mother too.) After we talked about this, my translation became ‘What’s up with that mother of yours now?’

At the beginning of chapter 2, Dad is enjoying a few leisurely moments with a cigarette. His thoughts wander and we read that ‘他忍不住就要开始想奶奶死了的事了’, literally, he can’t help thinking of Gran’s death. 想 can be ‘want ‘ as well as ‘think’ but I simply couldn’t believe that he really wanted his mother to die so I glossed ‘think’ into the noun ‘anxieties’ (about her death). One of Dad’s redeeming features is that he’s actually a properly dutiful son and he doesn’t acknowledge his deeply-buried hostility to anyone, even himself, so it seemed logical to assume that his thoughts were anxious. However, after you and I discussed Dad’s conflicted attitude to his mother, I changed ‘think/thoughts’ to the more ambivalent ‘daydreams’. I think there’s something that’s culturally very Chinese about this subtlety of language. Do you agree?

YG: Yes I do. I remembered when I first left China and lived in the US, I found people shockingly straightforward and it really took me quite some time to adjust. In general I think Chinese language is more abstract compared with English, and this allows a fluidity in both the langue and the culture. To be obscure is almost a virtue in China. Especially in this case, in the love/hate relationship with his mother, Shengqiang (Dad) cannot say what he really feels and he cannot even admit it to himself.

NH: There have been quite different reactions to The Chilli Bean Paste Clan, centring on a certain moral ambivalence in the story. Some readers can forgive Dad for being a profligate womanizer, others can’t. For Leeds Centre for New Chinese Writing Book Reviews, Kate Costello writes: ‘Yan Ge’s endearing if not entirely sympathetic characters grab you from the first page. Shengqiang (Dad) is delightfully dysfunctional from the very moment we lay eyes on him. He is a rare literary figure that manages to tear at our heartstrings even while we look down on his reprehensible behaviour and laugh at his vanity.’ While Amy Mathewson says: ‘…in this era of Trump and the #MeToo campaign, I found it difficult to laugh away the misadventures and foibles of Shengqiang. There is much awareness of the long-term effects of sexual harassment that has been highlighted recently and the treatment of the young hostesses by the older men during the drinking engagements made me cringe…’ Did you deliberately sit on the fence and avoid moral condemnation?

YG: Absolutely. I don’t think a good fiction writer should judge any of her characters. But at the same time I feel my stand was very clear. I remember we had a discussion when you were translating a particular scene (Dad going to a night club), and I expressed to you that the idea was to make the scene extreme and Dad’s behaviour revolting – and that was where I stand. I did not write the scene for the reader to appreciate or enjoy, I wrote it this way so the reader would be disgusted and see the absurdity in him and his world.

NH: You and I have talked and blogged quite a lot elsewhere about the challenges of translating Dad’s colourful obscenities, but here I’d like to say something about a different sort of challenge: how to translate the author’s hints without either giving the game away, or making the English so obscure that the reader is left bamboozled. Our novel is full of family secrets, hinted at throughout but only revealed at the end. We the readers have to guess what these secrets are, just as the protagonists in the story do. In the words of another translator, Natascha Bruce, ‘…the translator, somehow, has to be orientated enough not to spin things in ways [the author] doesn’t intend, and to notice the clues she’s laid for piecing things together.’ A key part of the denouement in The Chilli Bean Paste Clan are the commemorative couplets unveiled at Gran’s 80th birthday party, in which the calligrapher blows the whistle on Gran’s past life.

Here is the second line of the couplet in Chinese:

春娟百载,姜桂庭中迎灵龟。

May Spring Grace enjoy a hundred years, may the fragrant hall welcome the clever turtle.

Spring Grace is the name of the factory, and alludes to the personal name of its owner, Gran: 英娟, Brave Grace. The turtle is a common symbol of longevity in China, but in the famous erotic novel Plum in the Golden Vase, the clever turtle灵龟 refers to the hero’s penis, and the hinted-at appendage is getting a warm welcome! The allusion to one of China’s most famous classic novels defeated me and I omitted it on the grounds that it wouldn’t be recognisable to an English-language reader.

The lines are a sly reference to a secret from Gran’s past and they are intentionally obscure (the guests don’t understand the allusion, though Gran does and is mortified). They contain classical allusions and, dammit, the couplet has to rhyme! The challenge was to produce a rhyming couplet that hinted without telling. I ended up in English with this translation:

Long life to our distinguished Madame May

As we celebrate her eightieth birthday

Long life to the Mayflower Factory,

Where the fragrant vats embrace the stalk of longevity.

Wherein, in order to achieve a rhyme I was happy with, not just Gran but also the factory acquired completely different names. Having arrived at my translation of these four lines in the final pages (after an interesting discussion with you), I then had to go back to the beginning of the novel and re-name both the factory (making it the Mayflower Factory) and its owner (making her May and adding Madame in front for good measure).

One final question, you wrote this story, was it, eight years ago? Would you write it differently now? For example, because the cultural climate in Sichuan towns or in China has changed? Or because you feel differently as a writer and as a woman?

YG: Yes, it was eight years ago. (Where has the time gone?) Of course it’ll be very different if I write it now. For instance, I’ll not be that angry or maybe even angrier – who knows? The world I see is still puzzling and unsettling to me, and that is why I have to keep writing.